Stripped: Families say they were not compensated or inadequately compensated by Nkomati mine, which is 45km west of Barberton and 35km east of Machadodorp

Mining magnate Patrice Motsepe’s Nkomati mine in Mpumalanga has been accused of failing to compensate people correctly.

The former residents have now approached the Human Rights Commission (HRC) to investigate after numerous requests for the mine to speak to them about the relocation of dozens of graves and when development will happen.

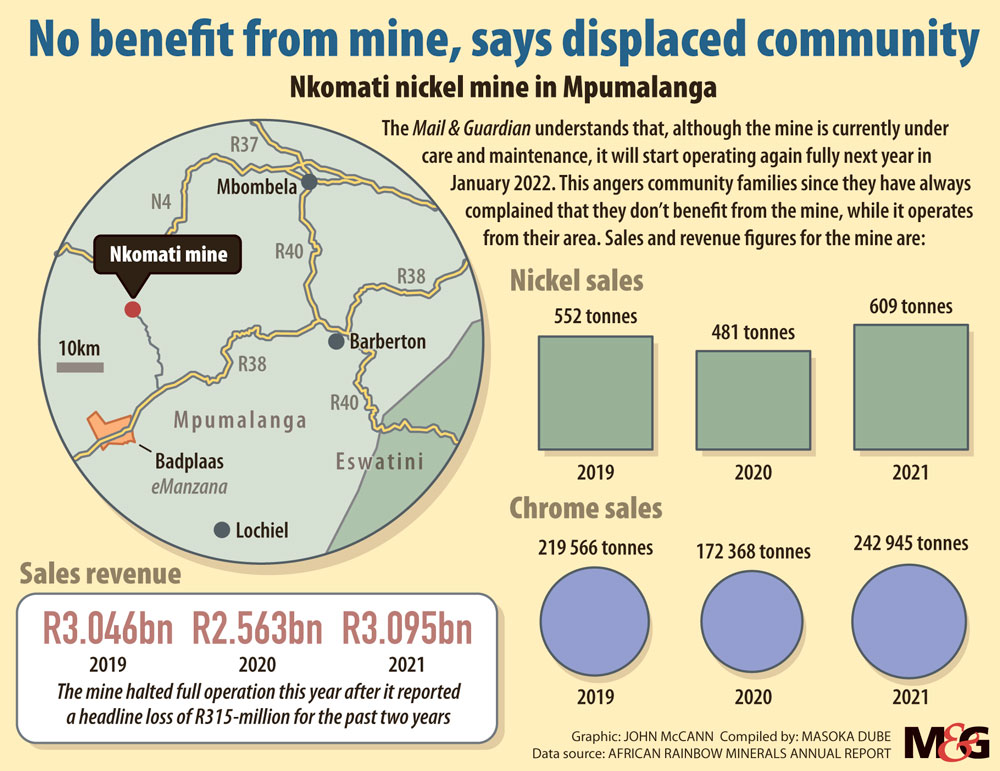

Nkomati mine, which is lo-cated between eNtokozweni (Machado-dorp), Emgwenya (Waterval-Boven) and eManzana (Badplaas), is owned by African Rainbow Minerals and Motsepe serves as its executive chairperson. The mine extracts nickel, chrome and other minerals.

There have been several other similar cases. Anglo American Platinum has been dragged to court after it allegedly failed to compensate relocated families whose graves were exhumed to make way for Mogalakwena, the largest open pit platinum mine in the world, outside Mokopane in Limpopo. In a case before the high court in Polokwane, Sekhukhune residents in Limpopo have begun litigation against mining companies that have allegedly failed to fulfil social labour plans to develop the areas in which they mine.

Back in Mpumalanga, John Vilane talks about the continual fight for compensation from Nkomati mine for graves that were exhumed and homesteads and cattle kraals that were demolished to make way for a site to dump asbestos.

It was 13 years ago when the mine convinced dozens of families, who used the land for growing crops, grazing cattle and a graveyard, to allow it to remove more than 25 graves.

The families had moved 30km away. Now their cattle are dying, their land is no longer conducive for farming and there has been no development in the area.

About 50 families allegedly entered into agreements with the mine.

Now several families are claiming that they never received any compensation and others say that the mine gave them R2 000 for only the exhumation and relocation of each grave.

“My family did not receive anything from the mine and we have been trying to convince them to compensate us for some time now and they keep on sending us from pillar to post,” said Vilane. “We started to communicate again early this year and the mine representatives promised that they would urgently attend to our problems, but they have not.”

Vilane said that 10 of his family’s graves were moved and there is no documentation to show what the agreement entailed. He believes the mine took advantage of older family members who were uneducated.

Another family member, Mdlali Vilane, said: “All we want for the mine is to compensate us and give us a document detailing the agreement that they had with our parents. Because our parents were not educated and they told us many things that the company promised them.”

The Vilane family is seeking legal advice to take the company to court.

A document seen by the Mail & Guardian states that an agreement was reached between the families and the mine about exhuming and relocating graves. The document does not mention the destruction of homesteads and kraals. According to the people the M&G spoke to, there are no other documents.

In an email exchange, dated 3 June, between the Vilane family and the mine’s representative, Herman Grobler, and its facilitator, Michael Nkomo, the mine promised to respond to the family’s concerns.

“Dear Mr Vilane, we are still in the process of obtaining additional documentation regarding the relocation of the graves and we will expedite this process to ensure we don’t waste your time and that of the family. We humbly request that you give us more time to gather all relevant documentation before we meet, ” the email reads.

But there were no discussions.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Attempts by the M&G to contact Nkomo were unsuccessful.

David Malunga, the general manager for Nkomati mine, has denied that the Vilane family did not receive its compensation but refused to show proof of payment. “Agreements were reached with all affected families and compensation was paid accordingly. No land was taken from families. All the affected families who signed agreements for the exhumation and reburial of human remains were compensated, including the Vilane family.”

Malunga said he was not obliged to produce proof unless the family, not the media, forced him to.

Some people feared being targeted if they spoke out.

One person, who did not want to be named, said he and others had approached the Human Rights Commission and the department of mineral resources and energy to investigate how the Nkomati mine was awarded rights over the land without proper documentation from the residents.

Neither the department nor the provincial HRC responded to the M&G’s questions regarding the investigation.

The Mpumalanga department of agricultural land reform and rural development referred all the questions to the mineral resources and energy department, which then refused to comment and referred the questions to the South African Heritage Resource Agency.

One person who did not want to be named said he and other residents had never supported the take-over of the land.

He said that his family had a large herd of cattle and, when they moved, the mine rented a small piece of land to be used for grazing. But this is insufficient for their needs and has cost him 12 heads of cattle.

Those who received some compensation said it was inadequate.

“After the deal, some of us were given jobs at the mine, but we got retrenched later,” said another person who requested anonymity because he is not authorised by his family to speak to the media. “All we need is our land back. We also need to see the signed agreement of the deal they had with our parents.”

The Nkomati mine halted full operation this year after it reported a headline loss of R315-million in the past two years. The M&G understands it will start operating again in January.

This is another matter that angered the families; they said they had not benefited from the mine, even though it was in their area.

The HRC said: “compensation to be meaningful, it should account for a loss of life; loss related to communal and individually held tenure or title as well as loss incurred for production value gained from the land; whether that production value is linked to traditional ways of life or more commercial enterprises.”

Research by the HRC in 2016 found that mining companies paid only for the land and were offering below what is considered to be appropriate and this causing systemic economic displacement and impoverishment.

The eMbhuleni Tribal Council, which would usually represented the affected people, says it was not involved in the issues relating to graves, and people dealt directly with the mine’s representative.

“I am aware that some families say they did not get compensation for their land and graves,” says Dan Khumalo, of the tribal council.

The mine’s Malunga would not comment on the allegation that the mine did not give what it had promised the people.

This article was possible with the support of the German federal foreign office and the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (IFA) Zivik funding programme. The views do not represent those of the German federal foreign office or the IFA