African Global Holdings: The corrupt company formerly known as Bosasa had assets illegally auctioned off in 2019 because the liquidators acted unilaterally, the Johannesburg high court found. Photo: Felix Dlangamandla

At its peak in the 2000s, Sipho Dube’s resources company employed more than 1 200 people and sold two-million tonnes of coal a year, 1.2-million tonnes of which was exported. That’s before the mining firm was “unlawfully” liquidated.

Today, Dube is angry that, more than three years after the public protector released a report showing gross maladministration that led to the liquidation of his company, nothing has been done to implement the remedial actions of the December 2018 report.

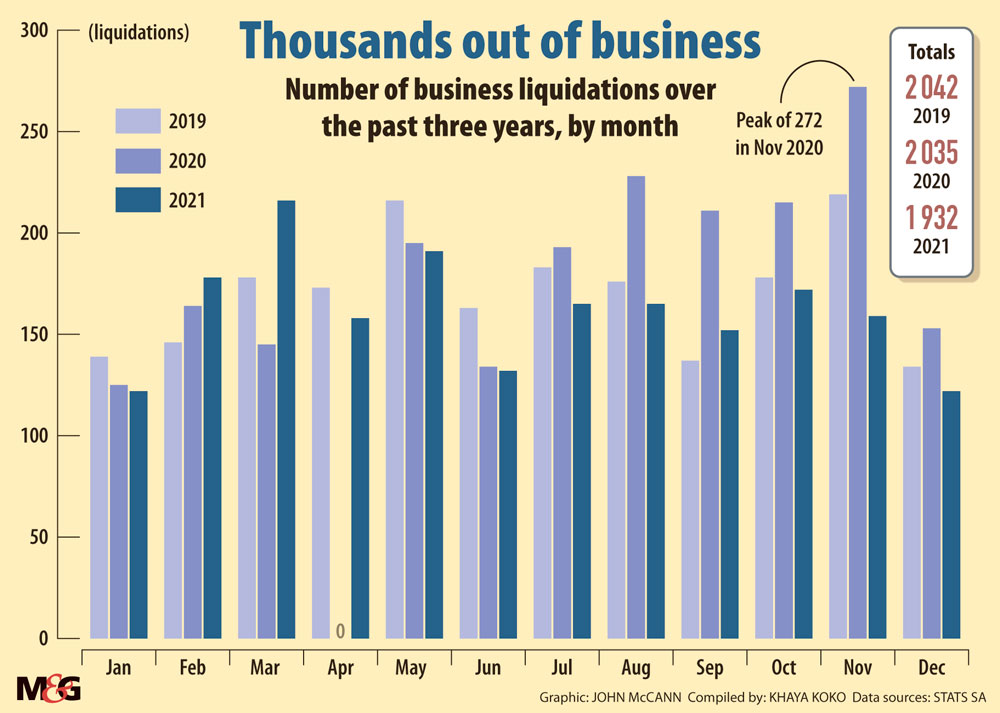

More than 6 000 businesses have been liquidated since late 2018, the bulk of them apparently as a result of the government’s failure to develop a policy that counters the activities of unethical liquidators, leading to the “unlawful” appointment and removal of liquidators that is “detrimental to vulnerable citizens”.

That December, public protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane released a report into the maladministration of the master of the high court, and directed the justice and correctional services department, within six months of the release, to “determine the policy regulating the appointment process of the provisional and final liquidators”.

Liquidation, which is either voluntary or an order of court, entails the closing of a company’s affairs when its liabilities exceed its assets.

“The policy should also regulate the process for the removal of the provisional and final liquidator by the master of the high court,” Mkhwebane recommended in the report.

The public protector’s investigation followed a complaint by Dube, the managing director of Endulwini Resources Limited, whose company was liquidated in December 2012 after what Mkhwebane found to have been an “improper process in appointing the provisional liquidator” in November 2011.

The report stated that the appointment of the provisional liquidator in Dube’s case was “characterised by gross irregularities and maladministration” that included the application of the 48-hour notice period, which is the period in which creditors can make requisitions or claims on the assets of the company being liquidated.

Mkhwebane said the 48-hour notice period by the master’s office in appointing liquidators was “too short, unreasonable, improper and prejudicial”, and was not documented in a policy of regulation determined by the minister of justice and correctional services.

“The 48-hour notice practices pursued by the master’s [office] in appointing liquidators rendered the process followed in [the] appointment of liquidators unfair, unjust and susceptible to abuse by unscrupulous lawyers and liquidators,” Mkhwebane contended in her report.

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian, Dube said he started his company in 1993, long before black economic empowerment laws were enacted in South Africa, with R1-million that he sourced from his grandfather’s trust fund set up for the family.

Endulwini operated at three mining operations across the country, specialising in coal and titanium products. Dube said he was hurt when the company was liquidated in what he felt was an illegal manner.

“That is why we approached the public protector’s office, because we could see the shenanigans of the master’s office. I was happy when we were proven correct, but very angry that nothing has been done by the government to fix the mess that office is in.

“We carried our employees for a year after liquidation, giving them a salary, until it became financially untenable to continue to do so,” Dube said.

“My proudest moment was the black professionals we recruited from established white-owned mining companies in the early 1990s. Those mining engineers and geologists were stuck doing clerical work when we approached them.

“The irony is that, when the empowerment laws came into effect after 1994, those same mining companies came back to poach the very same black professionals they saw no value in a few years prior.”

The M&G reported in August last year that the Special Investigating Unit probed shenanigans at the master’s office, including the appointment of liquidators by the master’s office, and the alleged interference of officials from the master’s office in favouring particular liquidators.

An example of the alleged unscrupulous behaviour of lawyers and liquidators can be gleaned from the August 2020 judgment by the high court in Johannesburg, which ruled that the December 2019 sale of assets belonging to African Global Holdings, formerly known as Bosasa, was “illegal and unlawful”. The judgment was delivered by Acting Judge Daniel de Villiers.

African Global Holdings, which is implicated in a range of fraud and corruption allegations for the government contracts it received, had its assets sold at an auction, which fetched almost R100-million, excluding value-added tax.

After the company launched an application to set aside the sale of its assets and the appointment of liquidators, the high court in Johannesburg ruled that the liquidators committed a slew of illegalities. For instance, assets can only be sold after a meeting of creditors, but this was not done in the case of Bosasa.

De Villiers said African Global Holdings’ assets were to be sold only with the consultation and consent of the company’s directors, which was not sought by the lawyers and liquidators.

“Without seeking to be unkind, [the liquidators’] version is that I must find that they had consent because they say that they had consent. The chronology clearly illustrates their version not to be a bona fide factual version,” De Villiers said.

“They could not refer me to any request for consent to the auction and its terms, who consented, when this happened, where this happened, or what the terms of the consent were given.

“The extremely disquieting aspect of this matter is that the provisional liquidators knew that they had not sought consent to the auction or the terms of the auction. They were challenged and they pressed ahead as if they [were] a law unto themselves.”

In her 2018 report, Mkhwebane had raised the issue of liquidators being “a law unto themselves”, finding that Endulwini Resources’ assets were also unlawfully stripped.

“The entire master’s appointment process was plagued with irregularities, as the appointed provisional liquidator had frozen all [Endulwini’s] bank accounts, including those of subsidiary companies that had not been provisionally liquidated, on 05 December 2011, which date preceded [the liquidator’s] appointment by the master. As a result thereof, the company was unable to meet its financial obligations including remunerating its employees,” Mkhwebane reported.

Theresia Bezuidenhout, who was suspended as the chief master last year pending an investigation into her alleged protection of corrupt staff, had told Mkhwebane that the South African Restructuring and Insolvency Practitioners Association successfully approached the constitutional court and interdicted a 2014 policy instituted by then-justice minister Michael Masutha.

Subsequent to that, no policy was determined by the department, Mkhwebane found.

“It is therefore my conclusion that [the] non-existence of the policy regulating the appointment and removal process of the liquidators is not only unlawful, but renders the insolvency industry monopolised to the detriment of the most vulnerable citizens, especially the companies under liquidation and the employees of those companies under liquidation,” she stated.

Oupa Segalwe, spokesperson for the office of the public protector, did not respond to questions about whether the office had followed up to check if its recommendations and remedial actions were adhered to and implemented.

Segalwe did mention the insolvency practitioners association’s successful constitutional court interdict against the 2014 justice department policy, and said the master’s office had launched a high court application to review Mkhwebane’s report shortly after its 2018 release.

“Although the review was not withdrawn, the master did not follow through with that process. There was a process to issue new regulations following the constitutional court judgment. However, it is not clear how far that process is,” Segalwe said.

Chrispin Phiri, the spokesperson for the justice and correctional services department, said the questions and the full public protector report the M&G had sent to him presented “a legal issue”.

“The report talks of a policy on appointment and removal of liquidators. There is no legal provision empowering the minister to develop a policy on the removal of liquidators?

“In light of this, I need to read the report with our litigation unit to understand what informs that conclusion and further understand if clarity had been sought from the public protector in this regard,” Phiri said.

Figures sourced from Statistics South Africa show that there have been a total of 6 009 liquidations from January 2019 to December last year. This is the period during which Mkhwebane’s remedial actions should have been implemented to further avoid the acts of allegedly unscrupulous liquidators and lawyers.

The most affected sectors last year were the financing, insurance, real estate and business services industries, with 625 liquidations, followed by trade, catering and accommodation, which was battered by lockdown regulations that resulted in 414 companies folding.

[/membership]