A picture shows damages after the shelling by Russian forces of Constitution Square in Kharkiv, Ukraine's second-biggest city (SERGEY BOBOK/AFP via Getty Images)

Conversations surrounding the crime of genocide are uncomfortable. The suggestion that a group, typically a minority, can be purposefully targeted and singled out for eradication, appears to belong to the realm of absurdity. The very need for the term in the modern vocabulary defies moral comprehension. However, given the outbreak of war and occurrence of potential war crimes committed by Russia, it is critical to understand the need for genocide awareness and prevention.

The term “genocide” is defined as “the deliberate and systematic destruction of a group of people because of their ethnicity, nationality, religion or race”. It was coined by prominent Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin during World War II, who used it to describe the atrocities committed by the Nazis during the Holocaust. It was later incorporated into the UN’s novel Human Rights treaty, vis-à-vis General Assembly Resolutions 96-I and 260-III. These resolutions, as well as Lemkin’s magnum opus Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, culminated in the UN cementing the international standard for genocide by adopting the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948.

Importantly, despite its 20th century introduction to the global legal stage, the crime of genocide is not a revolutionary concept. Descriptions of genocide have been lucidly documented in almost every inhabited continent and throughout almost every age. Perhaps the only novel concept regarding genocide is the modern world’s alleged aversion towards combatting it.

Given the geographic proximity to Ukraine, a poignant first example of the prevailing international incompetence regarding genocides is the Armenian genocide. Most modern scholars and historians consider the mass targeted killings of the Ottoman Armenians by the Young Turk government as an act of genocide. Reports show that an estimated 1.5-million Armenians were murdered from 1915 to 1917. Yet today, due to the sway of dollar diplomacy, weak international bodies and strategic alliances, many states refuse to acknowledge the genocide due to fears of backlash from Turkey. This lack of recognition entrenches the influence of state interests over the moral position and highlights the undesirability of international accountability through the recognition of genocides.

The Holocaust is another genocide emphasising the world’s incapability of standing up to tyranny. Despite accurate intelligence and eye-witness reports, European governments refused to intervene in Nazi Germany’s systematic destruction of European Jewry. Even after World War II’s end, several states refused entry for Jewish refugees, and others continued to assist prominent Nazis in escaping justice. Many governments and German companies which voluntarily collaborated with Hitler’s regime, are yet to compensate survivors’ descendants or investigate the wealth stowed away in vaults deposited by war criminals. Despite the international attention after the killings ended, the silence and inaction by foreign governments during the slaughter was deafening.

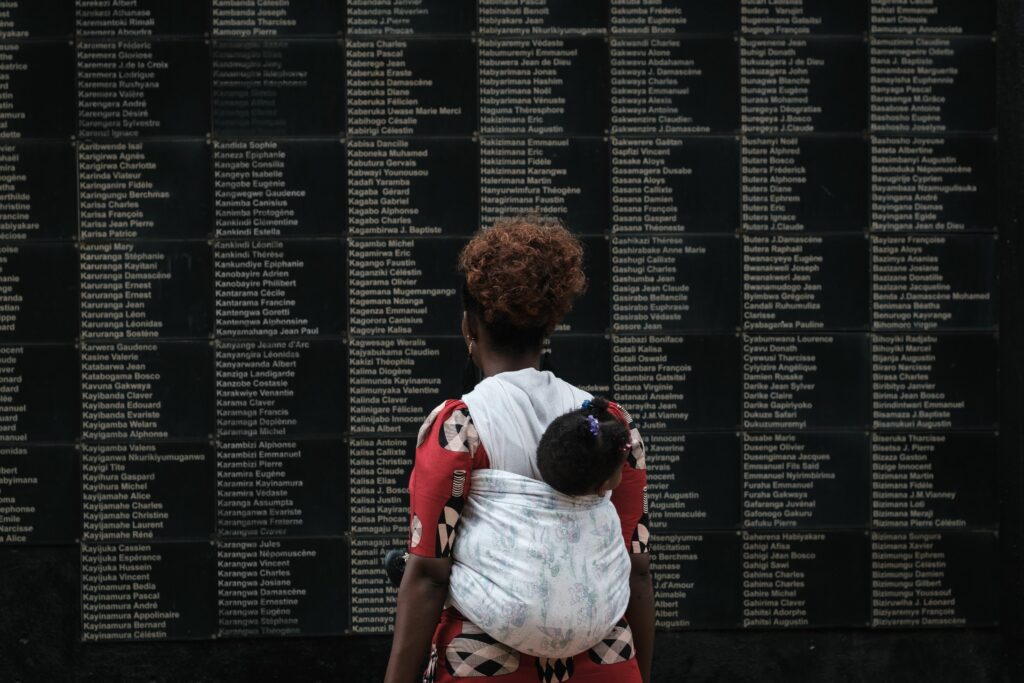

The case of Rwanda is a further rubicon crossed by the international community in its inability to both prevent or intervene during a genocide. Despite the warnings and clear signs of impending violence, the US decided to withhold military personnel from intervening in Rwanda, as did the UN, resulting in more than 800 000 Rwandans being viciously murdered within a mere 100 days after hostilities began in April 1994.

A woman looks at the wall of victims’ names as Rwanda marks the 25th Commemoration of the 1994 Genocide at the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Kigali, Rwanda. Critics have long asked how South Africa, the country of Nelson Mandela that fought against apartheid, could not do everything in its power to ensure the victims of genocide in Rwanda receive justice.(YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images)

A woman looks at the wall of victims’ names as Rwanda marks the 25th Commemoration of the 1994 Genocide at the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Kigali, Rwanda. Critics have long asked how South Africa, the country of Nelson Mandela that fought against apartheid, could not do everything in its power to ensure the victims of genocide in Rwanda receive justice.(YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images)

The list of international failures continues with the current treatment of the Uyghurs in Northern China. Unsurprisingly, the international community has failed to take effective action against the Chinese government for its “re-education programmes” and other “non-violent” designs, clearly displaying the dominance of financial interest over morality. As at the time of writing, no effective punitive actions have been levied on China. Clearly, the treatment of the Uyghur population is beneath the world’s moral quota.

These examples have left a dangerous precedent for the Russian military in Ukraine. Multiple governments and humanitarian organisations have labelled the actions taken by Russian soldiers as war crimes, while the UN has also condemned the violence. Additionally, punitive actions in the form of economic exclusion and crippling financial sanctions have also left the Russian economy in a bind. However, as historical evidence emphasises, the countermeasures enacted by the world may not be enough to combat potential genocidal actions in Ukraine. Putin has not shied away from expressing his contempt for Ukraine and is fully aware of the inability of international institutions and alliances to effectively sustain the current financial and moral pressure. Meanwhile Russia’s ally, China, can attest to the international impotence and moral fickleness present within the West’s ranks.

Unsurprisingly, this will not be Russia’s first foray into crimes against humanity. Although not recognised by most of the international community, the Holodomor genocide is a testament to a potential reality that may manifest in Ukraine. Many historians allege that from 1932 until the end of 1933, between 5-million and 10-million people died from a famine constructed by the Soviet government. Scholars who support the label of genocide highlight the inhumane actions of the Soviet government, which included the unsustainable requisition quotas of grain, introduction of food insecurity vis-à-vis harmful laws, and the refusal by the Soviet authorities to feed the population as the famine worsened, choosing to export grain rather than use it to feed the farmers who originally planted it.

As of 2022, Russia still formally denies the categorisation of the Holodomor famine as a genocide.

Unfortunately, in a world where morality is hamstrung by political interests and dollar diplomacy, a globally coordinated effort to address the failures of the past is the only way to prevent the genocides of the future. Although many believe that our modern moral compass and vast armies will prevent atrocities from occurring again, it is exactly that ignorance which will allow the escalation of violence around the globe to continue. Consequently, the discussion around genocide needs to change from dwelling in the past to combatting the current impediments to recognition and prevention of crimes against humanity.

Although governments and international bodies such as the UN, World Trade Organisation and Nato carry great importance in the fight against war crimes, the role of the individual cannot be understated. After all, these bodies are only as effective as the individuals within them. Consequently, it is imperative that we view ourselves as soldiers within the story of genocide prevention. Thus, the first step towards victory is arming ourselves with the knowledge of the past and the deeper causes of genocides.

A closer look reveals that it was human emotion that fuelled history’s many conflicts and genocides. By recognising that an emotion such as hate can propel mankind to commit atrocities, we simultaneously identify the power of the potential contained within ourselves. This realisation emphasises that while we are all capable of contributing to the destruction of humanity, we are equally capable of building a future of accountability and peace.

The only difference between the two realities are the choices we make every day.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.