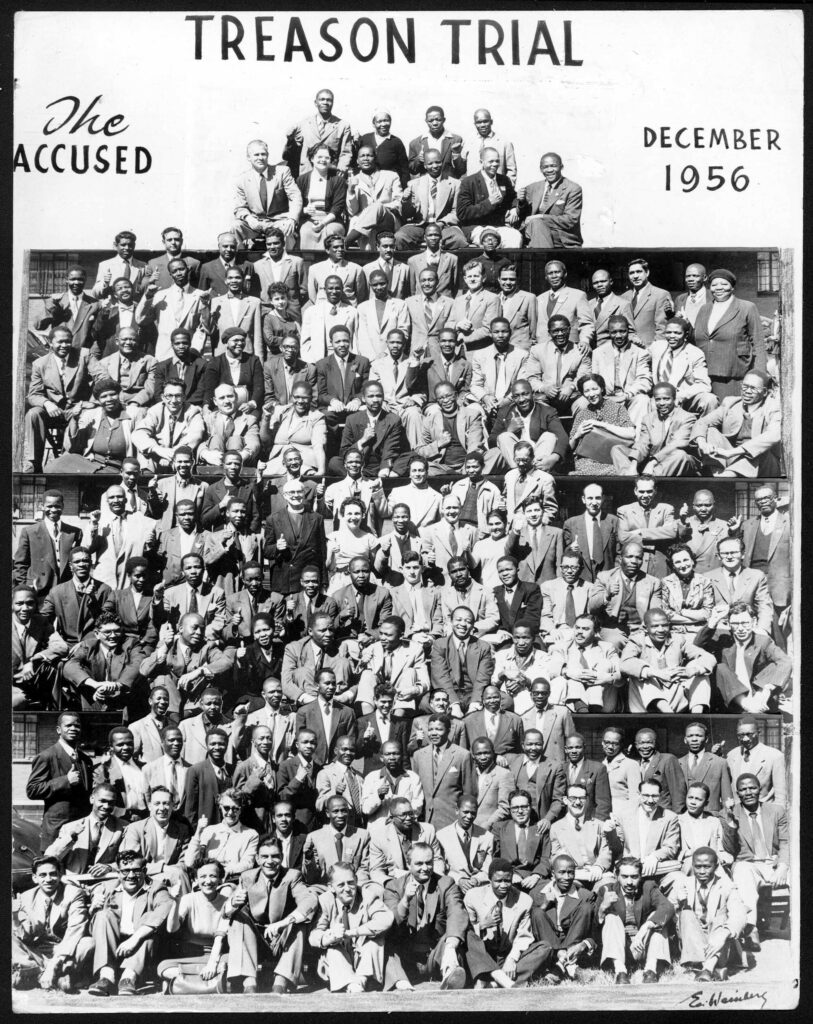

Free at last: ANC struggle stalwarts (from left) Raymond Mhlaba, Oscar Mpetha, Andrew Mlangeni, early life, which were Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Elias Motsoaledi and Wilton Mkwayi after their release from prison in 1989. (Photo: Sunday Times/Raymond Preston/Gallo)

It is an honour to be here this evening to celebrate with you the birthday of a true and committed stalwart of our struggle.

A giant amongst giants, a leader of our struggle, who embodied the very core of what our struggle represented and stood for.

Comrade Andrew’s selfless service to the cause is a mirror through which our struggle can be summed up: a person whose only concern was to secure the freedom of his people from the harsh and brutal oppression of apartheid.

His sense of justice and his desire for equality were imbued in him by his parents — parents who instilled in him a sense of duty and responsibility.

Before I say more about Comrade Andrew and his significant contribution — not to only our struggle for freedom but also to the building of our democracy, which was equally significant — it’s important to say a few words about his childhood and early life, which were formative in moulding Comrade Andrew into who he became.

Comrade Andrew came from a large family. He had 11 brothers and sisters. His father was dedicated and committed to his children and hoped the best for them, despite the limited opportunities available to black people at the time.

Although opportunities were limited, Comrade Andrew, from an early age ,displayed an inquiring and inquisitive mind and would not settle for his so-called prescribed station or lot in life.

In 1934 the family moved from the farm, where they had been tenants, to Bethlehem, where they lived with one of his brothers. It was while living in Bethlehem that Comrade Andrew displayed his tenacious determination and precociousness to learn and develop.

One of the friends he made while in Bethlehem was a boy by the name of Solomon, who would regularly disappear in the mornings.

His friend’s apparent disappearance tweaked Comrade Andrew’s curiosity. He was determined to find out where Solomon would disappear to.

One morning he followed Solomon to a building in the township, which he entered. Comrade Andrew followed him in and came across a group of children who, on seeing Comrade Andrew, burst out laughing. The lady standing at the front, in a commanding and strong voice, instructed the children to stop laughing, which, to Comrade Andrew’s surprise, they obeyed.

Unlike many other children of his age, his inquisitive mind exposed him to the concept and idea of schooling, something he had been unfamiliar with until the moment he entered the building. The encounter in the building opened a whole new vista and horizon for this eager and precocious boy.

Although he didn’t understand what school meant, he wanted to go back because he intuitively knew it was important and meant something. The young Andrew recognised that, through school, he would be able to progress and advance. Comrade Andrew’s zest and willingness to learn was vividly highlighted by his fortitude to pay his way through school and to support his mother. His commitment to support his mother showed his sense of duty, responsibility and commitment to others at a young age.

At the age of 12 he became a golf caddie to earn the money to pay his way through school. His exposure to golf through being a caddie clearly cemented his lifelong love and passion for the game. He is truly a golf fanatic.

Comrade Andrew, though, was not comfortable living in Bethlehem and moved to Johannesburg, the City of Gold, in the early 1940s.

At the beginning of 1944, he enrolled at St Peter’s College, Rosettenville, which was a mission school.

It was, however, no ordinary mission school: it was a fountain head of political awareness, consciousness and activism. St Peter’s was established in 1911 and it became the first secondary school for Africans in the Transvaal. Father Trevor Huddleston, who later served as its principal, was the very embodiment of this fountain head of political awareness, consciousness and activism.

A committed social activist for justice and equality, Father Trevor Huddleston, at the Congress of the People in 1955, was one of the first three leaders to be decorated with the ANC’s highest order, [the] Isitwalandwe Seaparankwe Medal, an order that Comrade Andrew became a recipient of in 1992.

The college was run by the Anglican Order of the Community of the Resurrection, and Trevor Huddleston was one of the priests of the community who was based at St Peter’s.

In fact, it was Trevor Huddleston who gave Hugh Masekela his first trumpet when the latter was a student at St Peter’s.

St Peter’s College soon became known as the “Black Eton”, at which academic achievements were realised.

Although Comrade Andrew obtained his junior certificate in 1946 he was unable to further his high school education because of financial constraints. Even though he was not able to complete his education, his political consciousness and awareness had been opened and activated during his time at the school.

He came to recognise that he could not stand idly by and watch his fellow African people being brutalised by an inhumane political system. He wanted to play his part and contribute to the liberation of his people and in 1951 he joined the ANC Youth League.

In 1954 he joined the mother body and became a branch secretary, and in 1958, until its banning in 1960, he was regional secretary of the South Western Area of Johannesburg.

After the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, as well as the banning of the PAC [Pan Africanist Congress] and the ANC, the latter decided in 1961 to move away from passive resistance to armed struggle. Comrade Andrew was one of the first six MK (uMkhonto weSizwe) recruits to undergo military training in China.

After the raid at Liliesleaf on the July 11 1963, the apartheid state decided to bring Comrade Andrew and Elias Motsoaledi, both of whom had been arrested in June, to the Rivonia Trial.

Ten leaders stood trial for sabotage … The trial was used by the accused not to defend their actions, but to put the apartheid regime on trial. Comrade Nelson Mandela, when he took to the stand, presented a compelling case to justify their actions.

During his statement from the dock on April 20 1964, Comrade Nelson said, and I quote: “During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

This poignant and indicative statement summed up the will and determination of the accused. It demonstrated the lengths they were willing to go to achieve their ideals of a free, non-racial, democratic South Africa.

A letter from Bram Fischer, their defence attorney, to a young comrade who was in exile, dated 24th June 1964, poignantly recalls the following: “I must tell you of one important event. Some days before the end of the argument in court, Govan [Mbeki], Walter [Sisulu] and Nelson came to an early morning consultation to tell us of a decision they had taken with regard to the sentence if it turned out to be capital punishment. They had made up their minds that in that event there was no appeal. Their line was that, should a death sentence be passed upon them, the political campaign around such a sentence should not be hampered by any appeal for mercy … or by raising any vain hopes … We lawyers were staggered at first, but soon realised the decision was politically unassailable. But I tell you the story not because of its political wisdom. I want you to know what incredibly brave men you and others will have to be successors to.”

Bram’s letter encapsulated everything that Comrade Andrew and his fellow accused articulated, represented and personified. A higher calling that went beyond the petty notion of “I”. Andrew and his fellow accused were the embodiment of true service and commitment to the people and the ideals of a “better life” for all as enshrined in the Freedom Charter.

To further highlight this, I would like to recall the following story. During the trial, Patrick Mthembu, who came from Dube village, and belonged to the same branch as Comrade Andrew had turned state witness. During his testimony, he at all costs avoided implicating Comrade Andrew and directed his evidence at Comrade Elias Motsoaledi, making him out to be the primary culprit.

Typical of Comrade Andrew, he raised this with the lawyers and queried as to why Comrade Elias Motsoaledi should bear all the burden alone. This concern and empathy for his fellow accused tells of the solidarity, courage and selflessness of Comrade Andrew and his generation. Comrade Andrew was not willing to allow a fellow accused to become a sacrificial lamb at his expense.

The Nelson Mandela Foundation said Andrew Mlangeni and the Rivonia Trial class represents selflessness that now appears to have been lost.

The Nelson Mandela Foundation said Andrew Mlangeni and the Rivonia Trial class represents selflessness that now appears to have been lost.

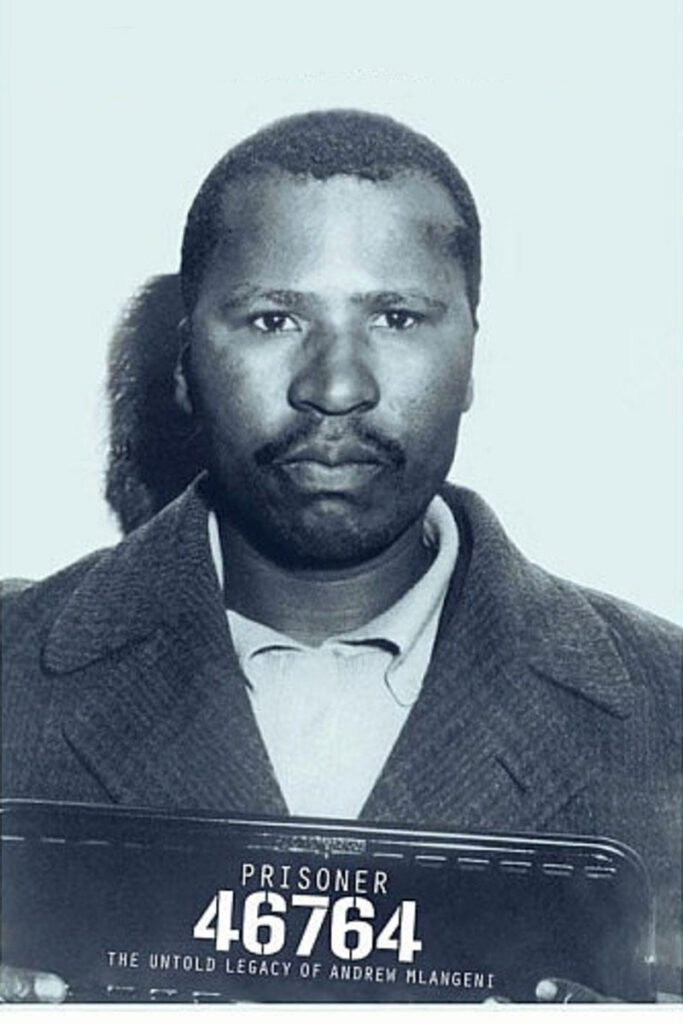

On June 26 1964, Comrade Andrew and seven others were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Following the sentencing, Chief Albert Luthuli, then president general of the ANC, stated: “In the face of the uncompromising white refusals to abandon a policy which denies the African and other oppressed South Africans their rightful heritage — freedom — no one can blame brave, just men for seeking justice by the use of violent methods; nor could they be blamed if they tried to create an organised force in order to ultimately establish peace and racial harmony. For this they are sentenced to be shut away for long years in the brutal and degrading prisons. They represented the highest in morality and ethics in the South African political struggle; this morality and ethics has been sentenced to an imprisonment it may never survive.”

Fortunately for South Africa, the apartheid state’s imprisonment of Comrade Andrew and the seven others failed to quell the spirit of the liberation struggle. They did survive and, although they were shut away, their indomitable spirit became the irresistible force for change.

On October 15 1989, Comrade Andrew, together with four of the eight Rivonia political prisoners, were released after 26 years of incarceration at Pollsmoor Prison and Robben Island. Among those released with Comrade Andrew were Ahmed Kathrada, Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba and Elias Motsoaledi.

As I conclude, we are blessed that we have in our midst this great revolutionary of our times and we should always remember that his and his fellow comrades’ struggle was not for posterity but to improve the conditions and lives of our people. This we should never forget.