Strong-arm tactics: South African Police Service officers enforce social distancing on 28 March during last year’s hard lockdown as shoppers queue

outside a supermarket in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. Photo: Marco Longari/AFP

It was one of the most horrific collective experiences we witnessed in post-apartheid South Africa. It wasn’t immediately apparent to those watching from home what had happened as Andries Tatane clutched at his chest. Within minutes, his death would be broadcast to millions of South Africans. Last week marked 10 years since Tatane was shot and killed by police during a service-delivery protest in Ficksburg.

Their weapon of choice? A rubber bullet discharged at close range.

A decade later, Tatane remains frozen at the moment of his death because justice has been elusive. The officers who shot him were ultimately returned to active duty; meanwhile, while his family and community have voiced their frustration that little of what Tatane fought for has come to fruition.

Hopes that the incident might trigger an introspective interrogation of public order policing have also proven to be horribly misplaced. Murder and violence have become routine in our society — from the countless people who have died in anonymity to the high-profile Marikana massacre.

Why do these incidents keep happening? How is it that a man going about his own business might be killed after wandering out of a doctor’s office?

And most importantly: How do we prevent this meaningless harm from being inflicted by those who are meant to protect and serve?

The strong arm of force

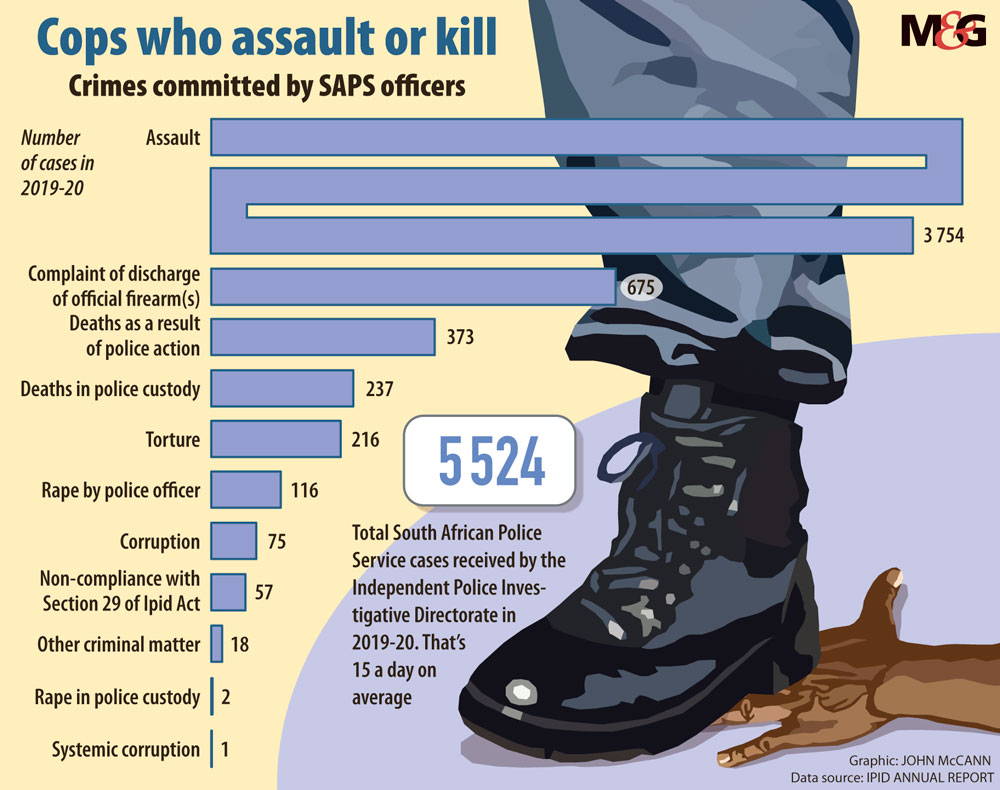

Determining the exact extent of police violence can be tricky, given that accurate reporting and appropriate oversight has historically been brought into question by several observers.

There is, however, enough evidence to support the natural intuition that this is a matter that deserves to be addressed.

According to data from the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (Ipid), 440 people died last year “as a result of police action”, slightly fewer than the previous term. This equates to a death every 20 hours on average.

Writing for Africa is a Country, researcher Paul Clarke argued that this equates to a rate far more egregious than the US — a country that has received unparalleled global scrutiny for police killings. Using data between 2014 and 2019, he found 7.96 deaths per one million people in South Africa.

Over the same period, the US recorded a per capita average of 3.37 deaths per one million people. (It’s worth noting that Africa Check called this comparison into question, citing a lack of data in both countries.)

The implementation of Covid-19 protocols would notch the use of excessive force by law enforcement to further up the public consciousness. Last year, parliament heard that 11 people had died as a result of police action between 26 March and 5 May, the period of the initial hard lockdown.

In handing down his ruling on the killing of Collins Khosa — who was allegedly assaulted by South African National Defence Force members while South African Police Service and Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department officers were present — Judge Hans Fabricius wrote: “No doubt they also have families that suffer under the present state of affairs and I am convinced that no father or mother in the security services would like to see their families be treated in the manner that others have been so visibly ill-treated.”

The extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic may have exasperated the situation, but public trust in those asked to enforce the law has been waning for some time. According to the Victims of Crime survey for 2017/18, published by Statistics South Africa, public approval of the police was at 54.2%, a drop of 10% over seven years. Further proof of the erosion of trust comes from the World Economic Forum which, also in 2018, reported that South Africans rated the reliability of our police services to “enforce law and order” as 118th of 137 countries.

Tracing the problem

It is clear that there is an inherent disconnect between the mandate of law enforcement and the perception of the execution of their duties. Many communities fear the police instead of looking at them as a source of protection; others resort to vigilantism rather than trust in the process.

“The police have become a frontline for the government,” says Lizette Lancaster, project manager of the Institute for Security Studies’ Crimehub.

“It’s almost the public against the police during protests. A lot of protests are against crime and violence; against the police; against the very people that are ‘managing’ these protests. It is a very toxic mix,” she says.

But how did we arrive at such a defeatist outlook on the law?

To many, the answer begins in understanding that our current structures are built on a legacy that did not serve the best interest of most of the population. In the context of the racist apartheid state, policing was politicised and had two key functions: to crush opposition to the government and control the movement of people.

The South African Police (SAP), as it was known before 1994, was a vital and detested organ of the apartheid regime. After it gained power in 1948, the National Party emboldened the force with powers to quash civil upheaval and discontent. Through legislation like the Police Act of 1958 and the Police Amendment Act of 1965, the SAP became a close ally of the military — its officers were eventually able to detain anyone and seize anything they perceived as a national threat.

Although the SAP did change with the addition of “Service” to its name, and various other organisational measures were tweaked, there is an argument that the changes were not significant enough to be considered transformative.

Over the past two decades, as crime has continued to rise, tough-on-crime messages, including some speaking approvingly of lethal force by the police, have come to dominate. With each police minister trying to out-macho the last, the statistics have mirrored the rhetoric.

The political leadership of the SAPS has repeatedly encouraged and excused police violence. On 17 August 2012, a day after the Marikana massacre in which 34 miners were killed, then national police commissioner Riah Phiyega congratulated officers for snuffing out the Marikana strike, saying: “[Your] actions represent the best of responsible policing.”

A view of the ‘large koppie,’ where men gathered during the strike of Marikana where 34 striking mineworkers were killed by police.

A view of the ‘large koppie,’ where men gathered during the strike of Marikana where 34 striking mineworkers were killed by police.

Remember when Bheki Cele was the national police commissioner in 2009 and instructed police officers to “shoot to kill” and “worry later”? Cele is the minister of police again at present.

A decade before that we had Steve Tshwete, a former safety and security minister, promising: “When we visit criminals we will not treat them with kid gloves … We will unleash the police force on them.

“We are going to deal with criminals in the same way that a bulldog deals with a bull… We are going to give them hell.”

It is this sentiment that has been recycled by almost all of his successors.

When we speak of police violence, we tend to think in terms of incident-based issues, instead of the structural failings at play, says Ziyanda Stuurman, a former policy researcher, who is currently communications co-ordinator for Southern Africa for Afrobarometer.

Collins Khosa was allegedly assaulted by South African National Defence Force members while South African Police Service and Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department officers were present.

Collins Khosa was allegedly assaulted by South African National Defence Force members while South African Police Service and Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department officers were present.

We have extremely shocking incidents such as the killing of Nathaniel Julies. Andries Tatane. Collins Khosa. But we never have full conversations about why this continues to happen.

“The problem was there was at least a perception that crime was getting totally out of control in the late ’90s and early 2000s,” says Anine Kriegler, a researcher with the Centre of Criminology at the University of Cape Town.

This made us scared to make the kinds of changes that would have actually been necessary to change the relationship between communities and the police.

“It’s really hard to make a non-militarised organisation when you perceive your situation as warlike, which is how the police see and experience their work on a daily basis — there’s a helluva lot of danger that they have to face,” Kriegler says.

The philosophy of the police as a military conduit is not necessarily a vestige of the past either. As recently as 2009, then-deputy police minister Fikile Mbalula made a concerted push to convert the service into a paramilitary force, replete with army ranks and discipline.

Mbalula — who that same year encouraged officers to “shoot the bastards” — was rebuked by ANC heavyweight Kader Asmal, who bemoaned: “This is a kind of craziness all of us have to take into account. It is part of that low-level political decision-making without reference to the cabinet.”

A way out

When we sit down to discuss ways in which public order policing can be improved, the good news is that an exhaustive document created for that very purpose already exists. The Marikana Panel of Experts Report on Policing and Crowd Management was released by Minister of Police Bheki Cele late last month … more than three years after it was first submitted to him.

Panel of experts report on policing and crowd management by Mail and Guardian on Scribd

The panel was set up after a recommendation in the final report of the Marikana commission — the body set up to look into the 2012 massacre.

Across 596 pages, the panel offers a scathing critique of the management of SAPS and its incoherent structures. Although it touches on the full gamut of law enforcement, the deliberate and predominant intention of the report is to reform public order policing so that we never again face the type of atrocity that necessitated its existence.

In total, the panel gave 136 recommendations. Of those, some are immediately actionable, notably the call for the use of automatic rifles — like the R5 which was used in Marikana — to be prohibited when dealing with crowd management. Others would see overhauls throughout the policing structure to introduce greater transparency and accountability.

Recommendation 15, for instance, calls for the establishment of an independent National Policing Board. This body would be “tasked with setting standards for recruitment, selection, appointment and promotion of SAPS members”.

On releasing the report, Cele provided assurances that most of the recommendations would be implemented in the near future and are, in fact, already incorporated into the South African Police Service Act Amendment Bill.

“This Bill has gone through a round of public comments and these inputs are being finalised before tabling the bill in parliament,” he said.

A man looks at the ‘large koppie,’ where men gathered during the strike of Marikana where 34 striking mineworkers were killed by police.

A man looks at the ‘large koppie,’ where men gathered during the strike of Marikana where 34 striking mineworkers were killed by police.

“The bill gives the assurance that no automatic rifles may be used in crowd control management. It will also address matters of vetting and integrity testing for those employed under the SAPS Act, including municipal police.”

Not everyone is taking Cele at his word, of course. David Bruce, for one, an expert who sat on the panel, took to radio to voice his doubt at the willingness and capacity of leadership structures to follow through with the recommendations. He pointed out that the report has “already been in the hands of the minister of police for close to three years and there hasn’t been, as far as I’m aware, any systemic engagement with the report”.

Stuurman would add that another medium-term issue that must be addressed is properly funding and capacitating Ipid.

The directorate has been systematically underfunded and defunded since 2014. Despite police budgets growing larger over that period, Ipid’s budget has shrunk, with offices closing in areas in which they are needed most.

The police budget was slashed by R1.2-billion in the last medium-term budget by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni. Ipid, already hobbled by cuts and downsizing, was slashed by R140-million.

Ipid can’t function properly with an underpaid staff complement and this may enable officers to act with impunity. “We as the public need to say you need to prioritise funding Ipid,” Stuurman says.

There has to be societal pushback, she insists, noting that citizens need to say we are just not seeing enough of a change or the police functioning as a service as opposed to a force.

No one minister will change the internal culture or structure, Stuurman concedes, as each minister comes in with a tough-on-crime attitude that ends up being at the detriment of South Africans.

The idea is to foster a new mentality — on both sides of the thin blue line.

“The main issue is that, whatever police do, they need to see communities and people protesting not as the enemy,” Lancaster says.

“We have eroded trust at a community level so much in the past 10 or so years through bad policing practises that it is incredibly difficult to now overcome this adversarial tension. It almost resembles what we saw in apartheid: it’s the police against communities,” she continues.

“If we don’t start improving trust in policing, through various ways, but also by simply in the way people are treated, we’re not going to see any change. I know it sounds fuzzy and airy-fairy but at its roots, police need to start being more accountable and professional: treat citizens like their clients, almost.”

Mourners surround the coffin at the funeral service for Andries Tatane in Ficksburg, South Africa on 22 April 2011. (Photo by Gallo Images/City Press/Leon Sadiki)

Mourners surround the coffin at the funeral service for Andries Tatane in Ficksburg, South Africa on 22 April 2011. (Photo by Gallo Images/City Press/Leon Sadiki)

Much is at stake at this pivotal point in the history of policing in South Africa. We have heard the victims’ stories; we have collected the data; we have held the commissions. The moment is now to ensure the right measures are implemented by those in power. It is not too late to ensure Andries Tatane did not die in vain.