Back to basics: Ndevana High School in rural Eastern Cape, like many schools, particularly in rural South Africa, has inadequate facilities. Photo by: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

Education leaders make the grade

Good progress has been made in unravelling apartheid’s systems of education but there is still a lot to be done to achieve equality

GRADE = D

South Africa has made bold strides towards transforming education, considering the major overhaul that was required from apartheid’s unequal systems of Bantu education and Christian national education — which was based on the philosophy that a person’s social responsibilities and political opportunities are defined along racial and ethnic lines.

But, despite the Constitution guaranteeing that every person has the right to “a basic education”, which the state is obliged to “make progressively available and accessible”, many schoolchildren in rural and township areas have poor education because of a shortage of teachers and inadequate school infrastructure.

Here’s how the country’s last five education ministers have fared in terms of delivering on their constitutional mandate.

Sibusiso Bengu (1994-1999)

Bengu did not leave an indelible mark on the education system after taking up the post at the start of democracy, with only a little improvement recorded during his tenure.

Granted, he inherited an atrocious education system where the majority of black children during apartheid had little chance of attaining a decent education.

Nevertheless, the number of pupils sitting for senior certificate examinations rose from 495 400 to 551 000 from 1994 to 1998 but matric exemption passes declined from 89 000 to 71 600.

The introduction of a new curriculum in 1998 — Curriculum 2005 (C2005) — was hampered because provinces did not have the finances to implement it, while many black schools in townships and rural areas remained overcrowded and barely functional.

Teacher commitment levels were at an all-time low and there were problems with the delivery of textbooks.

Bengu is not remembered for much, but what stands out is that he was criticised for cadre deployment at the expense of hiring experts.

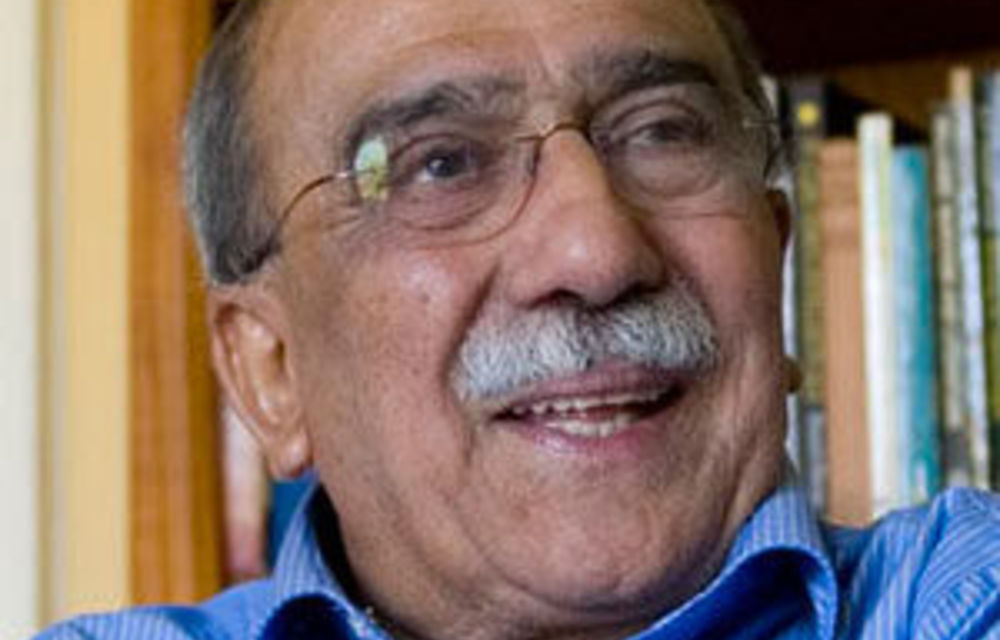

Kader Asmal (1999-2004)

Asmal inherited a chaotic department but did make improvements to the heart of the system.

He ushered in outcomes-based education (OBE) and ran with C2005, saying the new system reflected the government’s policy on education and would produce citizens imbued with the country’s values.

Asmal said OBE and C2005 “encouraged children to be aware of the full diversity of South African society: the rich array of races, ethnic and language groups, and the many religious belief systems which make up this country”.

But not all educationists approved of outcomes-based education.

Asmal also oversaw the production of a new curriculum for further education and training for grades 10 to 12 and initiated the practice of first-day ministerial school visits. The result was that the start to the school year — perpetually characterised by the non-delivery of textbooks, overcrowding and children being turned away, started to show a slight improvement.

Asmal received cabinet approval for the bulk of controversial tertiary-merger proposals across the country. But by the end of his term there were concerns about whether his policy initiatives would be sustainable and how much of the apartheid legacy remained. Outcomes-based education was eventually quietly shelved.

Naledi Pandor (2004–2009)

The exceptionally hard-working Pandor was committed to education and understood her portfolio. But the system she inherited was far from perfect.

Hampered by dismal performances at provincial and school level, with only isolated pockets of excellence, and a huge 50% university dropout rate, the ravages of apartheid remained tangible, as reports on educational quality illustrated.

South Africa came out bottom in a 2007 international study on reading, which surveyed mainly grade four pupils in 40 countries. After the study, Pandor announced a new strategy called a “foundation for learning” that included developing assessment tests in literacy and numeracy.

She also spearheaded an improved remuneration system for school teachers and realised the need to prioritise early childhood development.

To her credit, Pandor called out the “unacceptably high” underperformance in the sector, saying apartheid and inadequate resources could no longer be used as excuses for “failures on our part”.

She also advocated for free primary education and her department took steps to act against dishonest school managers who were inflating statistics about the number of registered learners and those who don’t keep records.

Sibusiso Bengu

1994 – 1999

Kader Asmal

1999 – 2004

Naledi Pandor

2004 – 2009

Angie Motshekga

2009 – present

Blade Nzimande

2009 – present

Angie Motshekga: basic education (2009 to present)

In 2009 the education portfolio was split into the departments of basic education and higher education. Unfortunately, after decades of opportunity to improve the sector, the basic education department under Motshekga still leaves much to be desired.

The 2021 edition of the international study on reading revealed that learners turning 10 had a very weak ability to read for meaning. South Africa scored 288 points, significantly below the centre point of 500.

In addition, the latest Trends in International Mathematics and Science study (2019) showed grade eight learners in the country have a substandard grasp of mathematics compared with those in other developing countries.

Teachers are lacking in both skills and qualifications. There were 1 575 unqualified and under-qualified teachers in classrooms in 2022 and a Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality study revealed that their knowledge does not measure up to their counterparts in the rest of the continent.

According to the study, teachers struggled to pass tests in subjects they taught. Grade six teachers achieved results of less than 50% — 41% for mathematics and 37% for reading subjects.

Under Motshekga the matric pass rate rose to 80.1%, the highest it has ever been.

But infrastructure problems remain huge. Many public schools still do not have libraries, laboratory facilities, computer centres or sports facilities. Pit latrines remain at many schools, there are still mud schools in the Eastern Cape and hundreds of schools in KwaZulu-Natal still have asbestos roofing.

Motshekga has also taken flak for the Basic Education Laws Amendment Bill, which aims to make grade R the compulsory start to formal schooling, and to make it a criminal offence for parents not to enrol their children in a school.

It aims to hold school governing bodies accountable for financial interests and gives department heads power over language policies and curriculums.

Blade Nzimande: higher education (2009 to present)

Nzimande’s tenure has been marred by the 2015-16 #Feesmustfall protests at universities, a problem he largely left to university vice-chancellors to handle instead of swiftly and decisively intervening.

The protests were sparked when students at the University of Witwatersrand started protesting in October 2015 in response to a 10.5% fee increase announcement. These violent protests then spread to other universities, causing an estimated R600 million in damage to property.

The students got their way when then president Jacob Zuma announced in 2016 that there would be no increase in university fees.

Student protests against financial exclusion flared up again in 2021 but this time, to his credit, Nzimande responded decisively, although not without controversy.

He met some of the students’ demands, including reopening the discussion on free tertiary education.

Importantly, Nzimande noted during the Commission of Inquiry into Higher Education that free higher education for all would not be possible in South Africa because it would not be fair to also extend this benefit to the rich.

He has demonstrated his support towards making education accessible to the poor and the “missing middle” (households earning between R350 000 and R600 000 a year) through a hybrid system of loans and bursaries through the department’s National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS).

The scheme is funding 1.6 million students, following “an unprecedented surge” in applications during the current financial year.

Despite being bedevilled by several problems and disagreements with direct payment service providers, NSFAS is arguably one of the department’s greatest achievements since 1994 because it represents a progressive model that has made university education accessible to those who otherwise would be turned down for student bank loans.

Over the past 30 years, the education department has achieved much to reverse the dual system implemented under apartheid and this should be duly acknowledged because it has been no easy task to steer around such a huge ship with limited resources, despite there still being immense work to be done to reduce inequality.

The department scores a D for its overall effort to serve learners adequately, although it does not always hit the mark.

Get the M&G’s take on other ministries over the past 30 years:

Department of Health

Department of Police

Department of Finance

Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment

Department of Human Settlements

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

Department of Public Enterprises