Headache: Despite efforts to provide homes, the relentless demand for housing with basic services in the country has not diminished over 30 years. Photo: Cuan Hansen/Getty Images

Housing ministers are a mixed bag

They have on the whole served satisfactorily, but the department has also been marred by decades of maladministration and corruption

GRADE = E

Over the past 30 years, the department of human settlements has improved the living conditions of millions of South Africans through the provision of housing and infrastructure for basic services such as electricity, water and sanitation.

South Africa’s latest census, 2022, shows that 88.5% of the population live in formal housing and that the number of traditional and informal houses has decreased. According to the 1996 census, just two years after democracy, 16.2% of people lived in informal dwellings. By 2022, this was 8.1%.

But the department has had its share of controversies — and the relentless demand for housing continues.

Joe Slovo

1994 – 1995

Joe Slovo

1994 – 1995

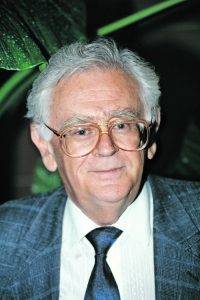

Joe Slovo (1994-1995)

As the first housing minister under Nelson Mandela, Slovo demonstrated commitment to get the housing task under way, not just because it was crucial to the government’s Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) but because it was an engine of economic growth and job creation.

Slovo made strides in setting up the legal, financial and policy structures to identify, expropriate, survey and develop land, and began negotiations with banks to facilitate finance for poorer families.

He convinced banks to service loans of R10 000 (when R30 000 was the usual minimum) to households with incomes as low as R1 000 a month (when the minimum requirement was R2 000).

Slovo faced conflict with provincial premiers who wanted to make their own plans rather than await central government decisions, and he had to placate restless people resorting to land invasions.

Slovo can be credited for laying a strong foundation for the infrastructure needed to embark on projects of a huge scale, no mean feat for a person only in the job for a year.

Sibusiso Bengu

1994 – 1999

Sibusiso Bengu

1994 – 1999

Sankie Mthembi-Mahanyele (1995-2003)

Mthembi-Mahanyele did not initially run with the baton handed to her by Slovo and her tenure was not without controversy.

She awarded a R190 million housing contract to Motheo Construction, represented by her friend, Thandi Ndlovu, and she sacked the director general, Billy Cobbett. These actions “continue to haunt the public perception of her … Prognosis: A coupé on the gravy train would do nicely, thank you very much,” the 1998 Mail & Guardian report card read.

Mthembi-Mahanyele lost her R3 million high court defamation suit against the M&G for the wording of the “F”-rated report card, and her case in the supreme court of appeal.

Her department made progress delivering homes but was criticised for constructing rows and rows of RDP houses similar in style to those of the apartheid government.

Perhaps disheartened by her meagre budget allocations and as housing dropped steadily down the national agenda, she showed little interest in the shacks that were mushrooming around the country.

In 2001, she announced that about five million South Africans had received formal houses since 1994, creating a R28 billion asset base for new homeowners.

She took steps to improve the quality of homes and consumer protection by requiring builders to register with the government, while promoting a savings-linked subsidy scheme for homeowners.

Mthembi-Mahanyele said it would take 15 to 20 years to remove “the scourge” of informal housing. She told parliament that many provinces regularly underspent on their budgets, which undermined the goal of delivering housing in the required volumes.

Tokyo Sexwale

2009 – 2013

Tokyo Sexwale

2009 – 2013

Tokyo Sexwale (2009-2013)

During Sexwale’s tenure, the title of the post was changed from housing to human settlements minister.

The purpose was to give him the power to plan integrated settlements and be responsible for sanitation and electricity but Sexwale was initially criticised for not dealing with the two factors. This could be attributed to a lack of policy direction and legal uncertainty regarding sanitation and electricity.

Sexwale dealt successfully with the longstanding N2 Gateway housing problem by relocating 10 000 shack dwellers to housing units. He also intervened in Lenasia where the Gauteng government was demolishing houses. He stopped the bulldozers and the public bickering.

Under his leadership the department recognised that in some cases it cannot remove people from shacks and pledged to provide them with water, sanitation and electricity through the National Upgrade Support Programme.

Sexwale also focused on transforming white residential suburbs. The strategy was underpinned by seven elements: white suburbs; inner city housing; inner-city land; outer city districts; towns and townships; upgrading townships; and new non-racial towns and cities.

The deracialising of white suburbs involved continuing to oblige banks through the Home Loan Mortgage Disclosure Act to provide loans to black people who wanted to buy property in white suburbs.

Inner-city housing was spearheaded by the Social Housing Regulatory Authority, which purchased many high-rise buildings in major towns and cities. The buildings were transformed from office space to rented family units.

Lindiwe Sisulu

(2004-09; 2014-18

and 2019-21). (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Lindiwe Sisulu

(2004-09; 2014-18

and 2019-21). (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Lindiwe Sisulu (2004-09; 2014-18 and 2019-21)

In 2008, Sisulu handed over more state-funded houses than any previous minister — houses with bathrooms and two bedrooms. Granted, she was standing on the shoulders of those who came before her.

She established the Housing Development Agency to remove the bottlenecks in housing delivery. But the agency later became embroiled in leadership struggles that hampered its work.

Sisulu has been criticised for her lack of concern regarding informal settlement dwellers. Her department was quick to resort to removing the homeless.

The controversy regarding her flagship housing project, the N2 Gateway, is a case in point. Joe Slovo informal settlement residents refused to be relocated to Delft to make way for the project, comprising government-bonded and free houses. Civil society groups criticised her after residents protested when she refused to meet them. She warned: “If they choose not to cooperate with government, they will be completely removed from all housing waiting lists.”

The project yielded 16 740 homes and cost the taxpayer R2.7 billion.

In 2021, her department was described in her M&G report card as “ground zero for so much corruption”.

Sisulu told parliament that there was a need to de-densify congested areas to contain the spread of the Covid-19 virus. The department, in a R2.5 million project, gave people transitional residential units — tin shacks, which cost about R64 000 a unit. These were located on sites from Talana in Tzaneen to Duncan Village in East London. Numerous units across the country had structural defects, others flooded during heavy rains, and parliament demanded to know how her department had accepted the price. MPs criticised her department for failing to enforce procurement standards and allegations of corruption arose.

Concerns were raised when Sisulu gave the acting chief executive of the Housing Development Agency, which had led the tin shack project, another six months to act in the position after the interim board had decided on a candidate.

Sisulu dissolved the boards of the Umgeni Water, Sedibeng Water and Magalies Water, some of which had been plagued by allegations of financial mismanagement and corruption and were owed more than R10 billion.

One of Sisulu’s main focus areas during her final stint was to order an investigation into her department’s more than R30 billion irregular and wasteful expenditure.

The operating business model for the Human Settlements Development Bank was also approved by the treasury, meaning it could lead financing activities across human settlements.

Connie September

2013 – 2014

Connie September

2013 – 2014

Connie September (2013-2014)

September was at the helm for a year, giving her little time to have much effect on the delivery of housing.

At the time she took up the post, there was a backlog of 2.1 million houses requiring R800 billion in investment if the shortage was to be dealt with in seven years, according to the Finance and Fiscal Commission.

September oversaw a shift in housing policy, initiated by President Jacob Zuma, to upgrade shacks and provide services to informal settlements rather than building more free housing for the poor.

The provision of housing and sanitation in rural areas was a problem and the department aimed to improve 400 000 informal settlements, at a time when the country had faced 3 258 service delivery protests from 2009 to 2012. Assisting middle-income earners gain access to mortgage financing was also a priority. The department’s ministerial sanitation task team found that people were still using the bucket system and that the department failed to spend R207 million of its operating budget in the 2012-13 financial year.

Mmamoloko Kubayi

Mmamoloko Kubayi

2021 – present

Mmamoloko Kubayi (2021–present)

Kubayi entered a quagmire of allegations of corruption, maladministration and fraud in the department.

She wasted no time in asking the Special Investigating Unit to look into allegations of corruption and illegal activity that had been reported in the department’s entities.

Kubayi also took immediate action to root out the alleged corruption by appointing new boards at several housing entities. The cabinet approved the appointments, which were formalised in March 2022, but these were not without controversy.

She defended her appointment of Steve Ngubeni, who had a history of financial misconduct allegations, as chairperson of the Property Practitioners Regulatory Authority.

Kubayi was determined to tackle the housing and title deed backlog of more than 439 000. Operation Vulindlela was introduced to accelerate the issuing of title deeds.

She also undertook to review the beneficiary process to ensure the allocation of houses and approval of households was improved after decades of complaints about manipulation and corruption.

According to a May 2022 department report, the government has provided about five million “housing opportunities” from 1994 to February 2022. The department said a further 38 7632 houses were built in 2022, and its target for 2023-24 is to construct 53 655 homes.

But Kubayi, responding to an auditor general’s report that she had been slow to provide temporary homes during flooding in KwaZulu-Natal, disappointingly blamed anti-corruption measures for the slow roll-out.

The department has uplifted the lives of millions of people, having delivered 4.8 million units/housing opportunities since 1994. Corruption, however, cannot be ignored. Millions more could have been uplifted without the immense theft and wastage.

Overall, the department earns the score of an E.

Get the M&G’s take on other ministries over the past 30 years:

Department of Health

Department of Police

Department of Finance

Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment

Department of Public Enterprises

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

Department of Education