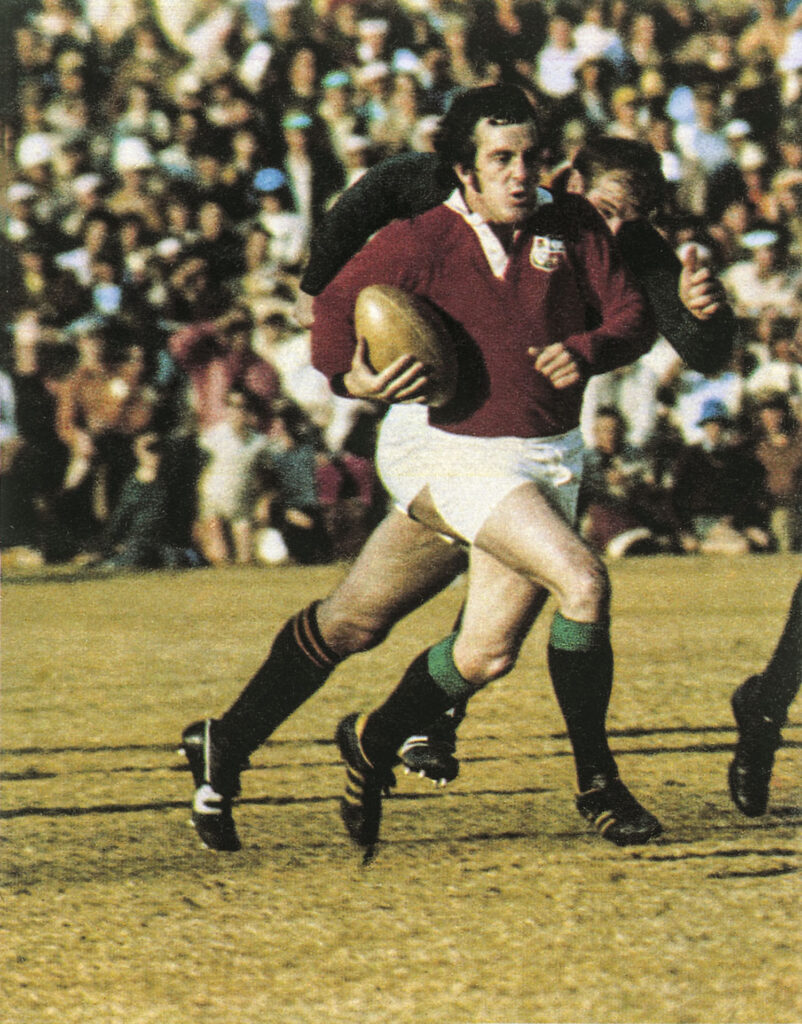

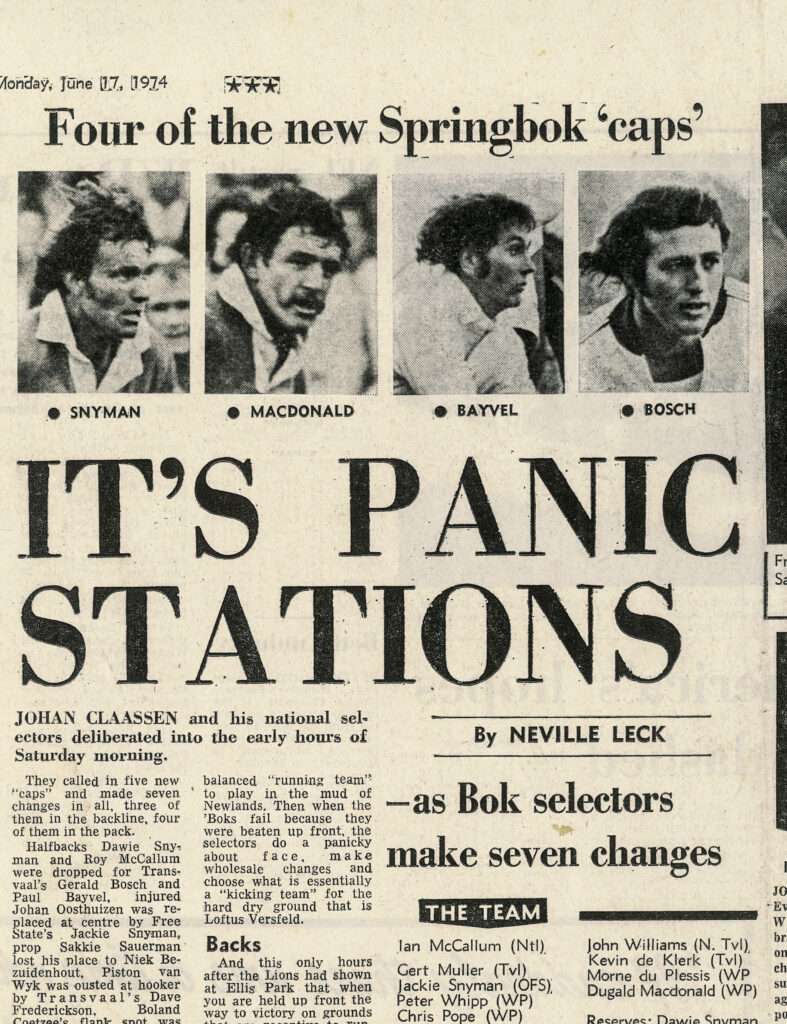

Dugald Macdonald was one of seven ‘unexplained changes’ to the ’Bok team for the second Test.

On 22 June 1974, Dugald Macdonald, a barn-storming eighth man from the University of Cape Town made his Springbok debut against the British Lions in the second Test at Loftus Versfeld. It was the biggest day of his rugby-playing life, but the portents leading up to the Test were not good. Springbok rugby had entered a paranoid phase. All was dark and in-turned.

For the first Test Macdonald was on the Springbok bench at Newlands. On the morning of the match the ’Boks caught their team bus down the Cape Peninsula to the pink stucco surrounds of the swanky Kalk Bay Hotel.

Sitting stiffly in their green blazers trimmed with golden braid, the ’Boks discussed the weather. Was it wise to play with or against the wind at Newlands that afternoon, wondered their captain, Hannes Marais, as he sipped his tea. The farmers in their midst such as Jan Boland Coetzee reckoned it was best to play with the wind in the first half, because it would die down as evening approached. Marais, fondly known as “Ons se Hannes”, took Coetzee’s advice — the Springboks started the Test with the wind at their backs.

Watching from the stands, Macdonald noticed that the touch judge’s flags were streaming rather than flapping. He saw the mud and felt the cold. The rugby was inconclusive, although the men in red, led by monster Ulsterman Willie John McBride, clearly had the upper hand in the scrums. The sides’ turned round with the score at 3-3.

As the second half progressed — with the Lions now playing with the wind at their backs — the wind showed no signs of abating as Coetzee had predicted it would. The Lions went ahead thanks to a Phil Bennett penalty; a Gareth Edwards drop-goal wobbled over the cross bar to make it 9-3 to the visitors. Ground down in the scrums by the powerful Lions front five, two of the ’Boks stand-out forwards, Jan Ellis and Morné du Plessis, were forced to scavenge behind a beaten pack.

Another Bennett penalty (12-3) put the match out of the ’Boks reach. When referee Max Baise eventually blew his final whistle, those sitting in the Newlands West stand blinked their eyes as if waking from a nightmare.

Penalties by Phil Bennett led to the Lions defeating the Springboks in the first Test

Penalties by Phil Bennett led to the Lions defeating the Springboks in the first Test

For the Springbok selectors it was now a classic case of stick or twist. Should they retain the same side and file the Newlands loss under “aberration”? Or should they reject their traditional caution in favour of a more freewheeling style on the Highveld, where the Loftus turf would be hard underfoot and ’Bok backs could hit their stride, something conditions had prevented them from doing at Newlands?

After deliberating for hours, selectors Johan Claassen, Butch Lochner and Ian Kirkpatrick decided to twist.

According to Macdonald’s recently published book, Ja-Nee: The Story Beyond the Game, he was one of seven “unexplained changes” for the second Test.

Amid public concern verging on anger, the ’Boks moved up to Pretoria. Practices were held in secret at the Baviaanspoort police ground. The team was forbidden to read the newspapers. There was a night-time practice. Here was rugby lockdown.

Macdonald remembers being approached by Kirkpatrick, who doubled as the backline coach, a couple of days before the Test. “You’ve got the ability to spark a team,” Kirkpatrick told him, but it was quite an expectation to fulfil. This was Macdonald’s first time in the green and gold jersey. He was simply a talented young player trying to do his best in circumstances stacked against him.

The son of a World War II paratrooper who had joined Tito’s partisans in Macedonia, Macdonald had grown up in Plumstead and attended Bishops school and liked nothing more than playing rugby or catching the train down to Muizenberg for an afternoon of surfing with his mates. When he read, it wasn’t Gustave Flaubert. He devoured anything by Ian Fleming he could lay his hands on. James Hadley Chase’s No Orchids for Miss Blandish was a favourite. In Ja-Nee he calls these authors “The Bastard Punks of Avon” and his book owes something to their hard-bitten, let’s-move-it-along style.

By the time they romped into Loftus the Lions had cut a swathe through South Africa, not only winning the first Test, but subduing their provincial opposition up front before skinning them out wide. Before the first Test, they’d beaten Eastern Province and then Western Province, one of the best provincial sides in South Africa.

They’d scored 43 tries in seven matches before reaching Newlands, nearly five tries a match. Perhaps it wasn’t the best time to flirt with “unexplained changes”?

From English front-ranker Fran Cotton to the Welsh Number 8, Mervyn Davies, all bases were covered in the Lions pack, with scrum half Gareth Edwards and his Welsh teammate, fly-half Bennett with his dancing feet. To expect Macdonald to spark a game was a big ask.

Perched high in the West stand that memorable Loftus afternoon was Gerhard Viviers, rugby commentator and doyen of the Afrikaans airwaves. Macdonald believes Viviers “invented South African rugby” and in a sense, he did.

“He turned moments into folklore,” writes Macdonald, with breezy precision. “‘Gerhard says’ settled arguments, quiz questions, bar fights, braai fights even. Every rugby club in South Africa had its Gerhard impersonator.”

Protesters demonstrated against the games. (Wessel Oosthuizen/SASPA)

Protesters demonstrated against the games. (Wessel Oosthuizen/SASPA)

Early on in his radio career, Viviers described HF Verwoerd’s funeral procession as it moved solemnly through Pretoria’s Church Square. A natural-born storyteller, Viviers needed more than an event like a funeral or a radio play (an early speciality) on which to discourse, he needed a subject. He found it in rugby, an epic narrative peopled by unsmiling sons of the African soil, who fought a long rear-guard action against pretty much everyone. Their vendetta was particularly sharp against folk from the north. Northerners drank too much warm beer in smoky caverns called pubs. The layabouts among them were propped up by something called the welfare state.

Viviers covered the traumatic 1969/70 Springbok tour of the United Kingdom, where the ’Boks were hassled by anti-apartheid demonstrators down the length and breadth of the land. He didn’t mince his words, describing the protestors as “long-haired sewer rats”, the offspring of a fatally permissive society. These tragic northern flaws were magnified when, once every six years or so, the British Lions ventured to either South Africa or New Zealand, bringing their talent but not their hearts. Unlike the dandies of the north, the grim men of the south were in touch with the wellsprings of their manhood. In the South Africans’ case, they tilled the soil (in magazines such as Huisgenoot Springboks were ritually photographed sitting on tractors) and spoke the language of that soil. Rugby was part of their culture and identity, their very being. It was one of the few things they had left as the world began to take an increasingly dim view of apartheid.

In the long minutes before kick-off at Loftus, Viviers knew what the stakes were. He knew that with South Africa becoming a pariah-state because of apartheid, isolation was around the corner. And he knew the Lions were both talented and hard.

As a result, he said, this Test “was going to be the most important match in Springbok rugby history”. If they lost at Loftus, no one would want to play them because playing any sport against white South Africa was becoming morally indefensible. “It might even be the end of international rugby for them for quite a while …”

That late June day in 1974, as they were heading to the changing rooms, the ’Boks were perturbed to hear singing coming from the Lions bus alongside. Led by the Scots’ winger, Billy Steele, the Lions banged out each verse of Flower of Scotland with crazy gusto.

“The Lions have a shared story: their memory of the bus, the song, the growing resolve, the sense that this would be their day,” writes Macdonald. “We Springboks have no shared story. Each will have his own story. For all, the common denominator would be the pressure and foreboding that pervaded the Springbok camp.”

The “pressure and foreboding” was indeed too much for the team of seven “unexplained changes”, of which the unfortunate Macdonald was one.

Worse still, they were a patchwork team of 15 individuals while the Lions had a very good idea of what the afternoon would bring.

They had already won the 1971 series in New Zealand 2-1, drawing the last Test 14-all, and this gave them the confidence to believe they might do something similar in another southern outpost.

Asked by Kirkpatrick to “spark a team”, Macdonald barely touched the ball all afternoon and neither did his team. Down by two JJ Williams tries to nil at half-time, the ’Boks leaked three more tries in the second half, their defence as full of holes as a colander. They eventually lost the Test 28-9, at the time the heaviest defeat in Springbok rugby history.

Despite Viviers’ incipient fears, the afternoon found him in stellar form, his merry vocabulary of “Noujas”, “platloops” (flatten) and “inklims” (climb in) at the ready. He even invented a few words. For the Lions’ third try, for instance, initiated by a twinkling run from deep by Bennett, he invented the word “hinkepink”, meaning to sidestep or jink.

Watching the video of the Test in his study all those years later, Macdonald is correct to point out that Bennett’s dizzy run starts with a “head dummy”, but he also admits that he can’t compete with the off-the-cuff brilliance of Viviers’ “hinkepink”. “It’s humiliating to be sidestepped,” he writes, “but there’s no shame in being hinkepinked.”

Discarded as part of an experiment gone horribly wrong, Macdonald never played for the Springboks again, discarded at the tender age of 24. His uncle, Pat Lyster, had played in the famous Springbok “Invincibles” to New Zealand in 1937. As a boy, Macdonald was asked if he’d like to put on one of Uncle Pat’s old Springbok jerseys and was thrilled at the prospect, cherishing the feeling for days. Now he’d done the real thing and it was all over, a nightmarish anti-climax.

After the Loftus defeat, Macdonald played at Oxford University for two years before finding himself at the sleeping giant that was Stade Toulousain, which was rousing itself. It was a heady time to be in the South of France, where he played in a back-row with two of the rugby world’s ultimate exotics, Jean-Pierre Rives and Jean-Claude Skréla. The glory years were just ahead and for Macdonald, it was no bad thing. He had much to forget, after all.

Ja-Nee: The Story Beyond the Game, is published by Flyleaf. An e-Book is available for Kindles on Amazon