Dean Elgar of South Africa reacts during day one of the First Test Match in the series between New Zealand and South Africa at Hagley Oval on February 17, 2022 in Christchurch, New Zealand. (Photo by Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images)

Who of us hasn’t experienced mild cognitive dissonance when it comes to thinking about New Zealand cricket? On the one hand — the rational part of the brain is speaking — the Kiwis played in the last two white-ball World Cup finals (in 2019 and 2021) and, even better, won last year’s inaugural Test championship by beating India by eight wickets in a one-off final.

That side, incidentally, is no more, for they are playing in the current Test against the Proteas in Christchurch without their two premier batters, Kane Williamson (elbow injury) and Ross Taylor (retirement). Even so, here is a smart, experienced side (particularly in the bowling), who play their cricket against the backdrop of an untroubled land where there is no history of political interference in matters cricket. They have reasons to be confident.

On the other hand — the emotional side of the brain here — the Kiwis ought somehow to be worse than they are. They have a tiny playing base and their players are seldom sought after as stars, say, in the Indian Premier League (IPL).

They live in the long shadow cast by their bumptious cricket cousins, the Australians, and the sport in New Zealand has neither the glamour nor the cachet of All Black rugby. They have no apparent right to be so good.

Once we get over such dissonance, however, we should be able to settle down and watch an enthralling two-Test series in Christchurch. Unusually, the summer has been hot in New Zealand, so the wicket at the Hagley Oval might be drier than normal.

This means that the teams’ respective coaches, Gary Stead (New Zealand) and Mark Boucher (South Africa), will probably consider their spin-bowling options at some point, because spinners could take advantage of a dustier, drier and, therefore, turning wicket. Ordinarily pace bowling wins the day in Christchurch; spin might yet, well, fizz into the frame in Test two next week.

The Proteas are a fascinating team at the moment, largely because Boucher and his Test skipper, Dean Elgar, have formed a solid, “I’ve got your back” partnership. Boucher didn’t start his international tenure in impressive fashion, losing a home series to England 3-1, but that was under captain Faf du Plessis, who sometimes looked too infatuated with his tailored cricket shirts (he had them specially made) and his sculpted hairstyle to bring a little mongrel into the Proteas dressing-room.

Captain Dean Elgar and Head Coach Mark Boucher of South Africa look on prior to day one of the First Test Match in the series between New Zealand and South Africa at Hagley Oval on February 17, 2022 in Christchurch, New Zealand. (Photo by Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images)

Captain Dean Elgar and Head Coach Mark Boucher of South Africa look on prior to day one of the First Test Match in the series between New Zealand and South Africa at Hagley Oval on February 17, 2022 in Christchurch, New Zealand. (Photo by Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images)

Elgar suffers from no such inhibitions. Stories came out of the recently completed Test series against India of the riot act being read to several players (one iffy instance with Kagiso Rabada was well-publicised) and flinty Elgar clearly doesn’t shy away from having difficult conversations.

He comes from Welkom (a clue here), and went to an unfashionable Catholic school, often travelling vast distances in dad’s car as a teenager because the only place that he could get a decent game of club cricket was in Bloemfontein. He’s had to battle hard for every inch of recognition and, finally, at 34, with 72 Tests under his belt, plaudits are coming his way.

He batted South Africa to victory in the second Test against India at the Wanderers, scoring a priceless 97 not out in the second innings, and went on to lead the Proteas to an astonishing 2-1 series win as a result of the victory in the third Test at Newlands last month.

Elgar is not spectacular tactically. But he and Boucher have galvanised their troops, making them conspicuously better than the sum of their parts. In some respects Elgar is beginning to remind me of another left-hander, Australia’s Allan Border.

“AB”, as he was known to all and sundry, was the quintessential Aussie battler. There’s some of that in Elgar and there’s needed to be — he got a pair in his debut Test against Australia in Perth in 2012.

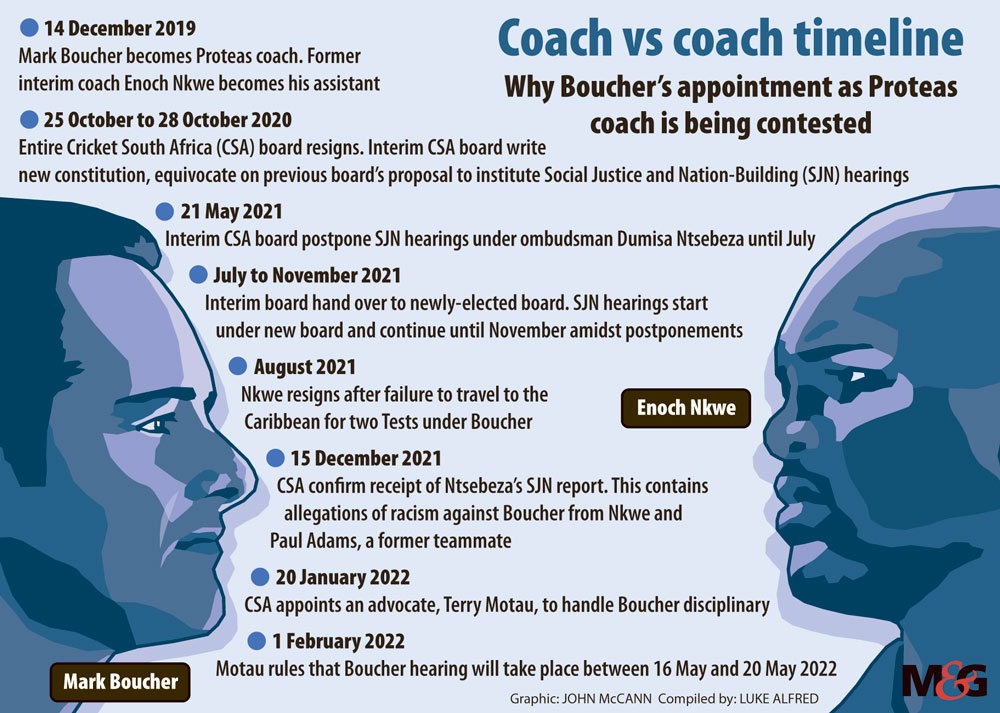

To some extent, Elgar’s cussedness is circumstantial. He’s said on several occasions that he neither knows nor particularly cares for the current crop of Cricket South Africa (CSA) suits, the very administrators he sees hauling Boucher before a disciplinary hearing chaired by advocate Terry Motau, in May.

The charges against Boucher in a seven-page charge sheet revolve around accusations of “racism” and “subliminal racism” levelled at him by Paul Adams, a former teammate, and Enoch Nkwe, his former assistant. Adams’s came in the context of last year’s Social Justice and Nation-Building (SJN) hearings, which shone a light on a persistent strand of racism — sometimes nasty; sometimes simply thoughtless — running through the sport.

Adams alleged that as a player in the late 1990s Boucher adapted the words of Boney M’s Brown Girl in the Ring to “Brown Shit in the Ring” and sung the song in team fines meetings. In his affidavit to advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza, the SJN ombudsman, Boucher did not dispute the allegation and apologised for the hurt he caused Adams. In his report after the hearings, Ntsebeza rejected Boucher’s apology, finding it “ignorant and ill-considered”.

Nkwe lost his job as acting team director to Boucher in the so-called crazy week of December 2019, becoming his assistant. Having apparently worked in relative harmony with Boucher for 18 months, Nkwe suddenly resigned in August 2021, citing concerns over the “functioning and culture of the team environment”.

In his exit interview with the CSA board he raised further concerns, prompting an internal investigation. “It wasn’t a deep dive,” one CSA board member told the Mail & Guardian, “but there was enough there for us to embark on these hearings. Once the accusations of racism against Mark surfaced, we couldn’t be seen to be doing nothing.”

During the May hearings (the cricket season is over by then) Boucher’s legal team will call witnesses, as will CSA, which is attempting to prove the charges of racism against him.

The players have said they will come to their coach’s support. Given Elgar’s comments on the suits and his general predisposition, he’s likely to be one of them. You don’t need to be blessed with spectacular gifts of prescience to see how destructive such a situation will be: the Test captain and the national coach bearing witness against CSA — their employer.

The rallying of witnesses works both ways. Adams and Nkwe will not only be called by CSA (because CSA’s case rests on their witness), but they also face the prospect of being cross-examined by Boucher’s legal team, who will comprise some of the smartest advocates in the land. Any shortcomings in their respective arguments will be ruthlessly exposed.

For the time being at least, we can put our exasperation aside and watch the cricket in New Zealand. From a South African perspective that’s not looking good so far. Boucher’s side capitulated and were bowled out for 95 on their first stroll onto Hagley Oval.

The summer may well be arduous and one Devon Conway will hope to flourish in the heat. An East Rand boy, once of St John’s College in Houghton, Johannesburg, he is now scoring runs by the bucketful for the Kiwis.

Writing in The Sunday Times 12 years ago, Ray White, the former president of the then United Cricket Board, said Conway “was the new Ricky Ponting”. People laughed him out of town. White might finally be proved right. After five Tests, Conway is going great guns, with three centuries (including one double-hundred against England). You can be sure he is licking his lips at the prospect of scoring one against the Proteas.