The City of Johannesburg has launched a sweeping climate action plan in which it commits to achieving carbon neutrality and climate resilience by 2050 to ensure “a cleaner, greener and a more liveable city for Joburgers to enjoy”. (Guillem Sartorio/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The City of Johannesburg has launched a sweeping climate action plan in which it commits to achieving carbon neutrality and climate resilience by 2050 to ensure “a cleaner, greener and a more liveable city for Joburgers to enjoy”.

Among its targets are that within the next 30 years, all residents will have access to safe, affordable and net-zero emissions energy; 90% of commuters will use public transport, walk or cycle; all buildings will operate at net-zero emissions; and all communities will enjoy clean air, be resilient to the health impacts of climate change and have enough food to eat.

“The way we plan our city, the choice of public transport [and] how we provide basic services will determine how our people are able to cope with the projected climate change impacts,” notes executive mayor Geoffrey Makhubo in the plan, which was launched last week.

The plan is ambitious, holds its own on a global scale, and is “doable”, says Megan Euston-Brown, a director of Sustainable Energy Africa, an urban energy and development organisation. “The ambition requires a ramping up of activity, but importantly builds on existing City of Johannesburg direction.

“The City’s existing sector plans were already very progressive, so it was a ramp up rather than a new direction,” she says. “Our experience of Joburg officials is that there is dynamism and substantial willingness to engage the public in ‘co-creating’ these plans.”

The plan, she says, was very rigorous in its development. “There were deep engagements with all the City sector staff and deep engagement with the evidence base. “The City has a particularly good team of greenhouse gas emissions monitoring staff within the environment and infrastructure services department. They really understand data and pulling it together, which is not an easy task.”

Sustainable Energy Africa has been the implementing partner of the C40- funded net zero carbon buildings programme, which the City is part of. “This takes the new building element of the plan into action. In this work, the City held an in-depth consultation process with financiers, developers, designers, low-cost housing companies, universities, the property owners association, province, national government, etc,” she says.

According to the plan, Johannesburg’s residents appear to be most vulnerable to increasing temperatures and heat island effects (urbanised areas that experience higher temperatures than outlying areas). “These are most dangerous in the poorer parts of the city that are home to highly vulnerable communities with limited adaptive capacity.”

Areas most vulnerable to drought, flooding and heat waves include Soweto, Alexandra, Ebony Park, Diepsloot, Roodepoort, Orange Farm, Lenasia and Ivory Park.

The Paris Agreement-compatible plan will implement emission reduction targets of 25% by 2030, 75% by 2040 and 100% (net-zero emissions) by 2050, as compared to the 2016 baseline.

It states that the biggest contributor to the city’s greenhouse gas emissions is stationary energy use by buildings and industry, which account for 54% of emissions in 2016, while the transport sector accounts for 35% of emissions — most generated by private vehicles — while the waste and wastewater sectors account for 11% of emissions.

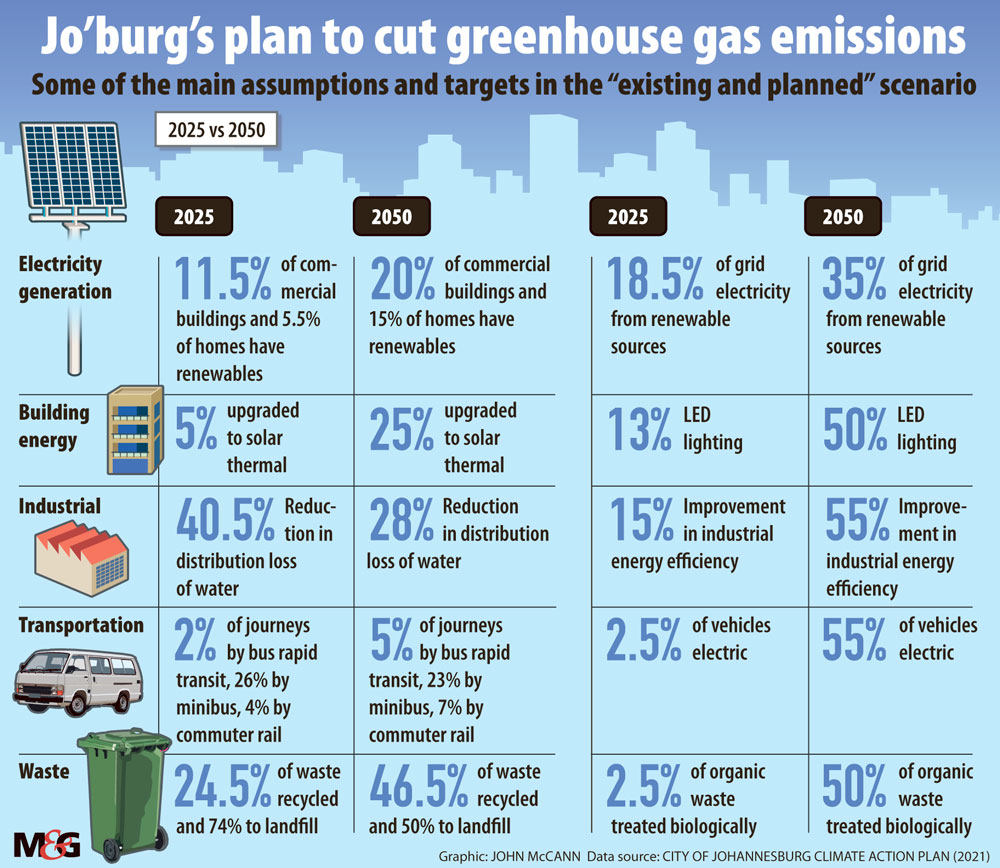

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The plan goes on to say that R10-billion in capital investment is needed for prioritised mitigation actions until 2050, as well as an annual operating budget of about R25-million for the same period.

“Key mitigation emissions reduction opportunities are found in energy efficiency (stricter building standards/codes) and renewables (grid decarbonisation and rooftop solar PV),” according to the plan.

“Transport emissions can be reduced through a modal shift from private to public transport, the use of cleaner fuels (electric and hybrid vehicles) and higher vehicle efficiency (vehicle emissions standards).”

Emissions from waste can be reduced by diverting solid waste from landfill (recycling and composting) and the use of wastewater biogas for energy production, it states.

The City will focus on enhancing water security, creating resilient human settlements, implementing flood and drought management strategies, developing resilient infrastructure and “enhancing the health and wellbeing of communities”.

The challenge, however, lies in the implementation of the plan, adds Euston-Brown. “Partly, we still need to see a similar level of commitment and real leadership from the national government across all sectors. Cities may lead from the bottom up on this work, but successful implementation will require national responsiveness.”

At the city level itself, there is a “disjuncture” between creative and globally impressive plans and the ability to deliver on the ground, says Euston-Brown.

“Joburg is experiencing explosive growth and this presents huge challenges. Infrastructure delivery is struggling to keep up and the City must ‘keep the lights on’ while also adjusting to the new climate ambition.”

New approaches, such as allowing rooftop solar PV to feed into the grid, often require “big system changes”, or “deep legal exploration to ensure that the public interest is being maintained”, according to Euston-Brown. This takes time and resources but Johannesburg – the City together with its citizens – “can lead the way”.

Professor Mulala Simatele, an environmental scientist at Wits University’s Global Change Institute, says while it’s a good start, the plan is “overly ambitious”.

“We can commend the City of Johannesburg for coming up with this very ambitious strategy that is very beautiful on paper. They capture all the nice things we need to hear about.”

But the city, he argues, fails to meet the minimal service provision for water, for example. “So, how are [we] going to deliver on these big things? … When we talk about sustainability, can we comfortably argue that South Africa’s institutions, which have been characterised by high levels of corruption and poor financial management, high levels of institutional fragmentation and silo approaches, will be able to implement a policy that talks about climate change action? My answer is no.”

The action plan will be challenging to implement. “It’s good on paper, but we now need to think about actually how we do it in a context where we have fragmented institutional and policy structures, where there is a silo approach where we are working. There is not an effectively aligned system at provincial, national, district and local levels. We are all struggling there.”

Nicole Rodel, of the African Climate Reality Project, welcomed the fact that the plan is inclusive of vulnerable groups such as women and youth, as well as the city’s ambition to mainstream climate change into other policies and plans.

“However, a noticed gap is that the plan has lumped methane gas with renewable energy sources such as solar and wind in their energy plans. Natural gas is a fossil fuel, and is a false bridge to clean energy that will not support the city’s alignment with a 1.5 °C goal,” Rodel says.

Julia Fish, coordinator of Fund Our Future, says she finds it encouraging that the City acknowledges the intersectional nature of both the climate threat and the alternatives.

“The plan is a holistic understanding that climate change impacts on poverty and access, not just the natural world. It remains to be seen, though, if the city is able to break free from the national energy plan and the country’s coal reliance.

“Transparency and sticking to staggered deadlines are not strong elements of the City at present, but the plan’s intent gives me optimism,” Fish says.