Hippopotami bathing at Lake St Lucia, in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park. Comprising of 280 km of coastline, iSimangaliso is South Africa's third-largest protected area. Watching hippopotamus bath in the evening is a popular tourist attraction. (Photo by Leisa Tyler/LightRocket via Getty Images)

It has been four months since the department of environment, forestry and fisheries committed to appointing a scientific task team to investigate why the estuary mouth of Lake St Lucia was artificially breached.

The breaching went against a 2016 high court ruling, in which the court found that the process of back flooding with a closed mouth is part of the natural dynamic of an estuary and to artificially breach it would harm the environment.

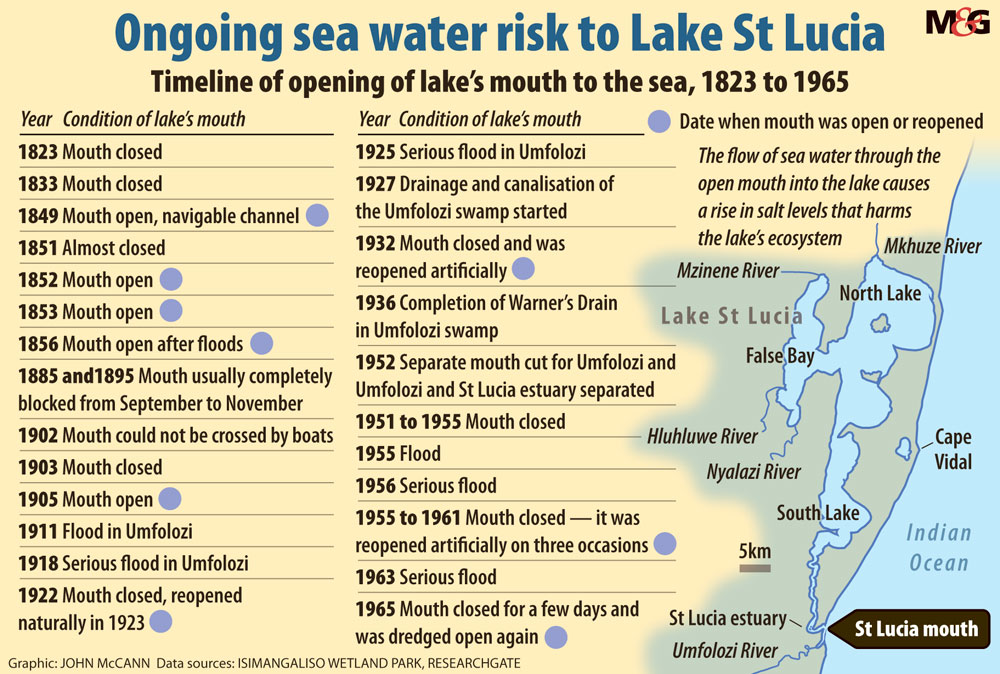

This was not the first time the mouth was artificially opened — and the rising threat of extreme weather means that it may not be the last, given the threat of flooding that affects the tourism and agriculture industries.

In January, scientists and environmental groups reacted with shock when the process to artificially open the Lake St Lucia mouth to the sea got underway. Scientists opposed the opening because of the risks it posed to the lake, which is in the Isimangaliso Wetland Park, a world heritage site.

The decision was taken to help farmers hit by flooding caused by effluent and invasive species clogging the Umfolozi River during heavy rains.

Minister of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Barbara Creecy had to intervene in February this year. She promised to appoint a team to investigate why the reopening of the mouth leading to the sea was justified, given scientific advice to the contrary.

Creecy said the task team would also investigate how the opening was linked to the Global Environment Facility (GEF) project to restore the ecosystem. This was to take place by reconnecting the Umfolozi River to Lake St Lucia, which had previously been artificially closed.

A tour guide explained to the Mail & Guardian in early June that invasive species were spreading fast on the lake and said he believed the sea water may help to clear the lake of some invasive species.

The iSimangaliso Wetland Park Authority, which manages Lake St Lucia, says it is possible that nutrients from effluent are promoting an increased vegetation response in the lake and the lower uMfolozi floodplain. It said the nutrients and increased sediments may facilitate the proliferation of alien plants.

“In recent years, the system has not been able to function naturally, resulting in several ecological challenges that called for urgent intervention with an intention of restoring the ecological functioning of this unique and dynamic system,” said Bheki Manzini, who heads communications for the park authority.

He said that interventions made thus far are part of the implementation of the St Lucia estuary management plan.

“The ultimate aim of the GEF project was the ecological restoration of the functioning of the St Lucia Estuary system. The assisted breach of the mouth was also for the very [same] purpose — to provide assistance to the system through human intervention. In relation to the assisted breach of 6 January 2021, the activity was not funded by the GEF,” Manzini said.

But, in an open letter to Creecy in January, a group of scientists said the park authority seemed to have abandoned its management strategy and ignored the scientific evidence on which the strategy is based.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

“In addition to committing significant time and effort to the GEF project and outcomes between 2010 [and] 2017, the iSimangaliso [Wetland] Park Authority also made a significant financial contribution to the GEF project, initially committing $12.7-million and then being able to leverage extra funds to extend this to a contributed total of $49-million to the restoration initiative,” the scientists wrote.

In a report in 2011 on the worsening eight-year drought situation, the park authority said the iSimangaliso Wetland Park was recognised globally for the area’s ecological processes, biodiversity, conservation history and superlative beauty. Covering an area of 239 566 hectares, the park encompasses marine, coastal, wetland, estuarine and terrestrial ecosystems.

The park has three major lake systems, the bulk of South Africa’s remaining swamp forests, eight interlinking ecosystems, old fishing traditions, coastal dunes that date back 25 000 years and more than 520 bird species. The systems include coral reefs, long sandy beaches, extensive coastal dunes, estuarine and freshwater lakes, inland dry savanna, and woodlands and wetlands of international importance.

The scientists who wrote the open letter were part of a group overseeing a World Bank research project to protect the estuary. They condemned the artificial breach as going against the scientific findings of the GEF project, which ran from November 2014 to February 2017.

“The major recommendation from that project was that natural processes should be allowed to re-establish; the Umfolozi River should be allowed to rejoin the Lake St Lucia estuary, and allowed to fulfil its dual role as a source of freshwater and a driver of mouth inlet dynamics. It specifically recommended that no artificial breaching of the mouth was to take place,” the seven scientists wrote.

The scientists told Creecy that the actions taken on 6 January were contrary to the outcomes envisaged.

“We hope that the current pathway can be halted and the restoration of this estuary brought back to a scientifically robust and data-driven process,” they wrote.

The department of environment, forestry and fisheries did not respond to the M&G’s request for comment by the time of publication.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa