Pangolins at the Johannesburg Wildlife Veterinary Hospital NPC which specialises in the treatment and rehabilitation of indigenous wildlife

Cash is king for those on the lower rungs of the illegal wildlife trade in South Africa, but further up the supply chain, payment methods and laundering tactics become far more sophisticated.

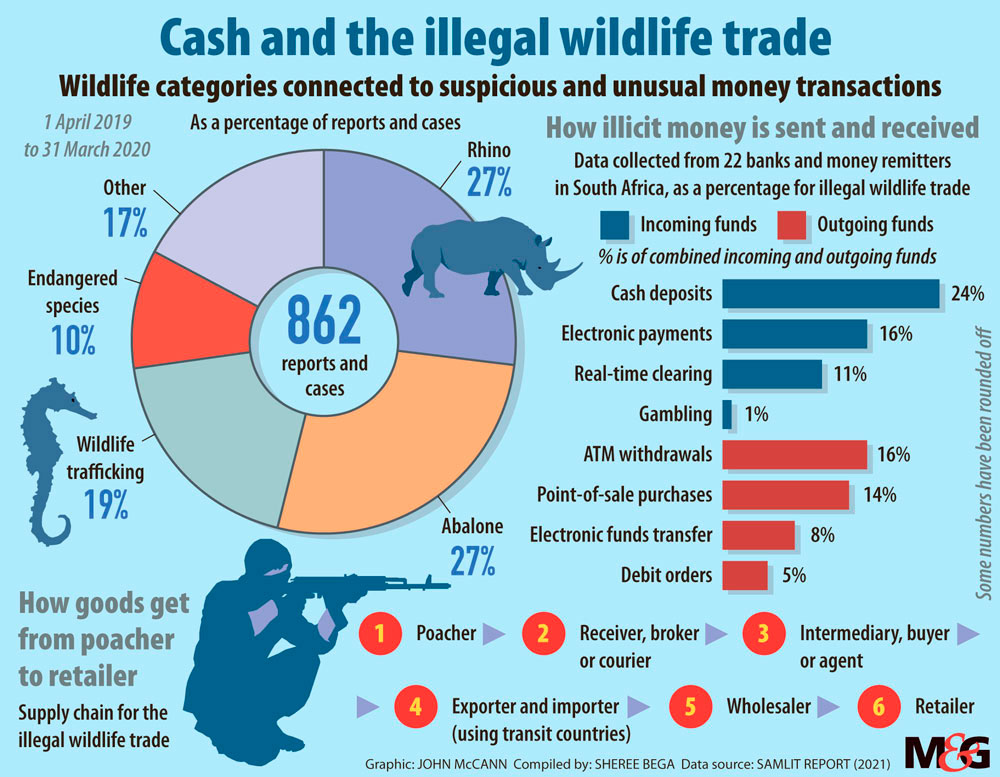

How the money flows in wildlife trafficking has been detailed in the first report of its kind by the South African Anti-Money Laundering Integrated Task Force (Samlit), a private-public partnership established by the Financial Intelligence Centre.

It was compiled using interviews, surveys from local banks and money remitters, data-mining, suspicious transactions and activity reports, and reviewing investigated cases.

What is striking, Samlit says, is the simplicity and ease with which both wildlife and financial crimes are committed. This could be ascribed to an incomplete understanding about the trade and its associated financial flows, the suspected use of informal financial schemes such as hawala and payment with mechanisms that evade the formal financial system such as barter, casino chips — or simply the use of cash.

“The extent to which front companies are implicated in illegal wildlife trade crimes is alarming, especially those linked to import and export activity and cash-intensive businesses,” reads the Samlit report.

The accurate identification of illegal wildlife trade-related financial flows has been identified as the biggest challenge facing financial institutions, “given the similarities with other crime types and the co-mingling of transactions associated with legitimate business”.

Investigators identified various payment methods for incoming and outgoing funds linked to accounts under investigation. “Characteristics of these payments were round amounts, large amounts, cash deposits and withdrawals conducted from various locations in South Africa, card purchases abroad, casino spend and money remittances described as gifts.”

Globally, the illegal wildlife trade is among the most profitable criminal enterprises, valued at up to $23-billion a year.

South Africa’s diverse wildlife means it plays a “devastating role” as both source and transit country for wildlife trafficking. The most popular animal parts include rhino horn, abalone, pangolin and ivory, which is moved through South Africa to the East.

Facilitators of wildlife crime and corruption include politically influential persons (domestic and foreign), diplomats, officials from the department of forestry, fisheries and the environment, the South African National Parks, the South African Police Services, the Special Investigating Unit and municipalities. Others are those employed in leisure, tourism and hospitality industry, veterinary surgeons, environmental practitioners, butchers and taxidermists.

The use of the legal wildlife industry to mask illegal trade is prevalent and includes wildlife breeders, the hunting and taxidermy industries and legal wildlife trade exporters.

Data mining shows deposit references such as “secret”, “happy”, crypto currencies, luno/VALR, complicated codes such as YISHANGLVYO-UXI5223630003110768; taxidermy; villa payment; hunting trophies; hunting package; MOOLA and names such as Lin, Chen, Liang, Gao, Huan and Qian.

Poachers are mostly paid in cash or “send-cash” options that create vouchers redeemable at retail till-points or ATMs. “Cash is the preferred and most frequently used method of payment as it minimises the risk of detection and allows for easier flows between legal and illegal economies,” the Samlit report reads.

Cash is often laundered through the purchase of vehicles or boats (for abalone poaching) and the construction industry, where building materials are bought with cash, after which houses are sold legitimately.

“Cash-in-transit and transport industries feature heavily in the illegal wildlife trade industry. Cash intensive businesses such as Chinese shops or markets easily combine illegal cash with other legitimate cash deposits,” says the report.

Electronic fund transfers (EFTs) are primarily associated with people involved higher up in the supply chain. Syndicate leaders make payments to members for miscellaneous expenses, including vehicle hire and domestic accommodation, making it difficult to establish links to those involved in the trade based on transaction descriptions or references.

The report states that it’s hard to establish the main person controlling the syndicate because of the complexity of the transactions “where various business and personal accounts are used to co-mingle funds”, as well as the use of a spouse or relative’s account on the main member’s behalf.

Front companies and enablers may appear to be legitimate, but the analysis of their transactions pointed to large incoming flows and showed few legitimate business expenses.

Money mules are paid by a syndicate member to either allow them to take over their bank account or open a new bank account in their own name. “This way the syndicate can transact without being directly linked to crime,” says the report.

Illegal wildlife trade funds move across borders through EFTs, money service businesses and informal remittance systems, particularly into offshore accounts, while casinos and retail stores are often used to transfer funds back into South Africa.

Currency coming into South Africa is often American dollars and euros, while funds leaving the country are in American dollars, Canadian dollars, euros or Thai baht. This is moved out through cash smuggling and money transfer systems.

Unusual cash deposits and EFTs into park rangers and other informers’ accounts and unusual cash spending for flashy or expensive items such as cars, houses and boats particularly in areas close to the Kruger National Park and other nature reserves “should ring alarm bells”, warns the report.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Suspects caught for poaching or trafficking can seldom afford legal counsel or pay bail “but often end up doing so through support from higher levels in the syndicate”.

One respondent noted a case where vouchers (iTunes and Google Play) were purchased from a supermarket with cash to be sold online. “On raiding a property, the police confiscated rhino horns, as well as R2.7-billion worth of vouchers, which had been originally purchased via one supermarket,” stated the report.

Prepaid cards (iTunes, Visa, phone cards) provide a “convenient and portable currency” whereby traffickers can pay for poaching and related services in source jurisdictions, and transfer funds internationally. Prepaid cards (iTunes, Visa, phone cards) provide a “convenient and portable currency” whereby traffickers can pay for poaching and related services in source jurisdictions, and transfer funds internationally.