The world is heading for a nearly 3°C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels under current climate pledges, the latest United Nations report has warned.

The world is heading for a nearly 3°C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels under current climate pledges, the latest United Nations report has warned.

The Emissions Gap Report 2023 released by the United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) on the eve of the COP28 climate summit in Dubai found that pledges under the Paris Agreement put the world on track for 2.5°C to 2.9°C global warming above pre-industrial levels this century unless countries amplify climate action. The predicted 2030 emissions must be slashed by 28% to 42% compared to current policy scenarios to get on track for the 2°C and 1.5°C goals of the Paris Agreement. The Earth has warmed by 1.2°C.

Achieving the Paris Agreement goals hinges on strengthening mitigation this decade to narrow the emissions gap, according to the report’s findings. This will facilitate more ambitious targets for 2035 in the next round of climate pledges and increase the chances of meeting net-zero promises, which cover about 80% of global emissions.

“The 2023 edition of the Emissions Gap Report tells us that the world must change track, or we will be saying the same thing next year — and the year after, and the year after, like a broken record,” wrote Inger Andersen, the executive director of Unep. Humanity is breaking all the wrong records cords on climate change, she said.

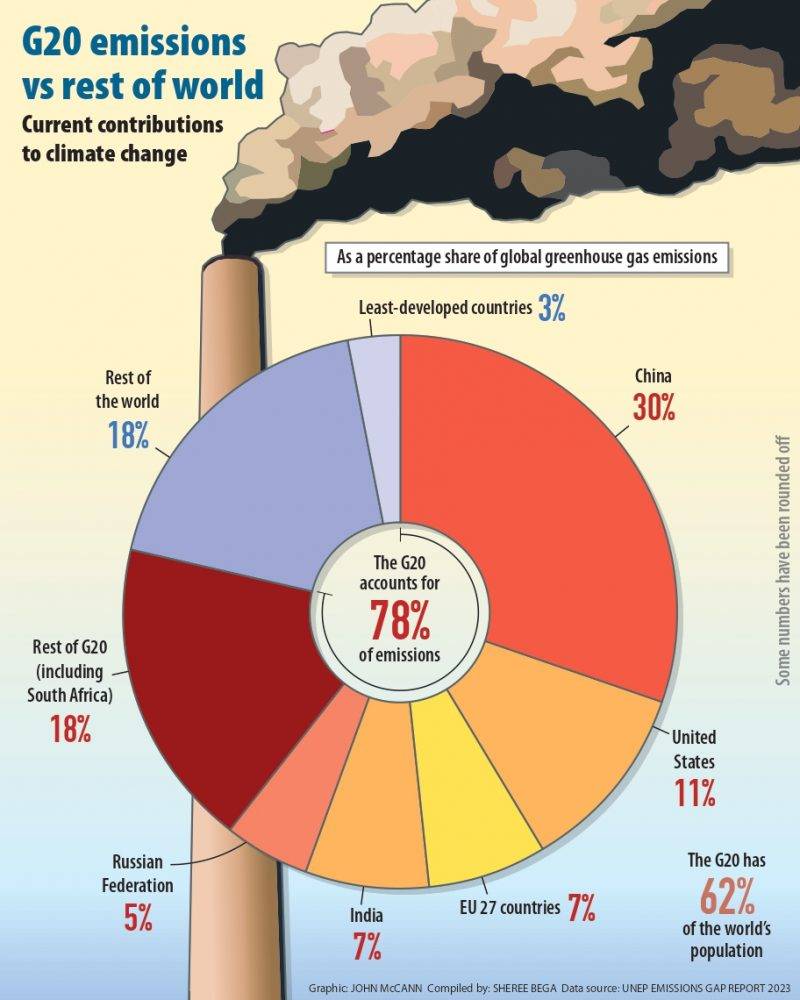

Global greenhouse gas emissions increased by 1.2% from 2021 to 2022 to reach a new record of 57.4 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Similarly, GHG emissions across the G20 increased by 1.2% in 2022.

Fully implementing and continuing efforts implied by unconditional nationally determined contributions (NDCs) would put the world on track for limiting temperature rise to 2.9°C. The additional achievement and continuation of conditional NDCs would lead to temperatures not exceeding 2.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

In the most optimistic scenario, where all conditional NDCs and net zero pledges are met, limiting temperature rise to 2°C could be achieved. “However, net-zero pledges are not currently considered credible: none of the G20 countries are reducing emissions at a pace consistent with their net-zero targets. In the most optimistic scenario, the likelihood of limiting warming to 1.5°C is only 14%.”

The report said energy is the dominant source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 86% of global carbon emissions. “The coal, oil and gas extracted over the lifetime of producing and under-construction mines and fields as at 2018 would emit more than 3.5 times the carbon budget available to limit warming to 1.5°C with 50% probability, and almost the size of the budget available for 2°C with 67% probability.”

Global transformation of energy systems is thus essential, including in low- and middle-income countries, “where pressing development objectives must be met alongside a transition away from fossil fuels”.

Last month, Forestry, Fisheries and Environment Minister Barbara Creecy told the national stakeholder consultations on COP28: “Where we are starting to get to in the international negotiations is who is going to use the remaining carbon budget.

“Developing countries are saying we should use the remaining carbon budget because developed countries have managed to secure the prosperity of their citizens on the basis of the climate crisis we’re now suffering. And of course, once you get into that question then there’s all kinds of hypocrisy you’re starting to deal with,” Creecy said.

This raises several issues, said Jesse Burton, a lead author of the Emissions Gap Report (EGR) and a senior energy policy and just transition researcher at the Energy Systems Research Group at the University of Cape Town.

“The EGR this year shows that the remaining ‘carbon budget’ — the amount of emissions we can emit globally for a given temperature target —for 1.5°C is very close to exhausted already, and the existing fossil fuel infrastructure far exceeds that. This means globally there is already too much fossil fuel being produced or planned, and too much emitting infrastructure — so already globally we are looking at stranding some of these investments, these investments that are rapidly becoming climate liabilities.”

Who “gets” that remaining budget is a critical part of the debate. “If you apply a ‘fair shares’ lens — a lens that looks at countries’ historical emissions, their capability to act, which South Africa has done for its own targets — it is clear that developed countries have far exceeded their share of the budget,” Burton said.

“They continue to exceed it, leaving very little space for developing countries for critical investments in the short term, where existing technologies are not yet fully decarbonised but are necessary — for example steel, cement, mobility.

“So, in that respect the minister is absolutely correct, and there is a lot of hypocrisy, where very rich countries, who have emitted significantly, are also developing new oil and gas resources for export for example, and using up more and more of this scarce budget.”

On the other hand, Burton said, “we need to be critical about whether those international debates support local development, because the answer is that often the situation on the ground is that fossil fuel extraction doesn’t lead to benefits for people and communities, or even countries overall.

“Do fossil fuels still serve as drivers of development? This isn’t so clear to me anymore. Certainly energy services — the ‘things’ that energy does for us, like lighting, cooling, refrigeration, mobility — and energy access are critical, and delivering this to people who lack access needs to be massively scaled up.”

The main question is what does it mean to be prosperous in a future world without fossil fuels, Burton said. “And in turn, what stops the developing world from being able to move into new technologies. And then we come full circle to the international debates, because one of the fiercest and most vicious aspects of the international negotiations is about finance and how to make sure that those who need it most can be supported to transition.

“Because of the lack of carbon budget, the inequality in its use described above, everyone now has to go so much faster, but we don’t see financial flows, including grants from developed countries, matching the effort being demanded from developing countries. And some of the largest emitters continue to fail to pay their fair share of the finance that needs to flow to developing countries.”

(Graphic:John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic:John McCann/M&G)

Burton said that probably the most important thing for Africa overall in the low carbon development transition is energy access. “Africa is really being left behind in the roll-out of electricity and clean cooking, and we see the International Energy Agency reporting that fewer people have access in recent years.

“Turning energy investment towards scaling up new supply, new electricity networks and connections, clean cooking options, is critical for human development, for health and well-being, and for education.

“Avoiding new emissions is a co-benefit of that, but the reality is that energy access is critical for dignity, for small business to thrive, for economies to grow in and of itself. And while renewable energy is often the cheapest new supply option, it is capital-intensive, and so again finance is a key part of the solution here.”

Global change expert Nick King said: “The key point is simply that the longer we take to transition, the more difficult it becomes, for a number of reasons. First, the committed finance to major energy infrastructure projects, which become stranded assets, causing huge financial losses and turmoil to national economies — the loans will still need to be repaid.

“Second, extreme weather events become more extreme and more frequent. In addition to the human cost of lives lost, property damage, etc, this also means damage to old and new energy infrastructure, again meaning significant financial losses and disruptions across the economy — energy, transport, manufacturing, agriculture, health and education.”

Third, most of South Africa’s fossil fuel energy infrastructure, including Koeberg, is at or nearing end of life. “Thus it needs to be replaced, so why are we quibbling about whether to refurbish and keep these going, and build new coal-fired power stations when renewable energy is cheaper, more easily decentralised [and] can reach many more people?”

Given that huge infrastructure such as coal-fired power stations have an intended lifespan of about 50 years “taking us to around 2080, it’s inconceivable that anyone thinks they will still be functional then”, he said. “We need an urgent overhaul of our energy systems and thinking strategically about what it all means for 10, 20, 50 years ahead — it’s not about solving load-shedding now.”

Burton said South Africa is seeing progress through the Just Energy Transition Partnership to manage the effects of the transition from coal and building new areas of competitiveness in new-energy vehicles, for example. “But there are still many new mines being developed and we are not adding new generation capacity quickly enough to address supply insecurity, demand growth, or decarbonisation,” she said.

“New renewable energy, new networks are key here, but also focus on the developmental aspects of the transition, trialling new ownership structures, supporting local manufacturing and value chains can be part of South Africa’s development strategy for the 21st century.”