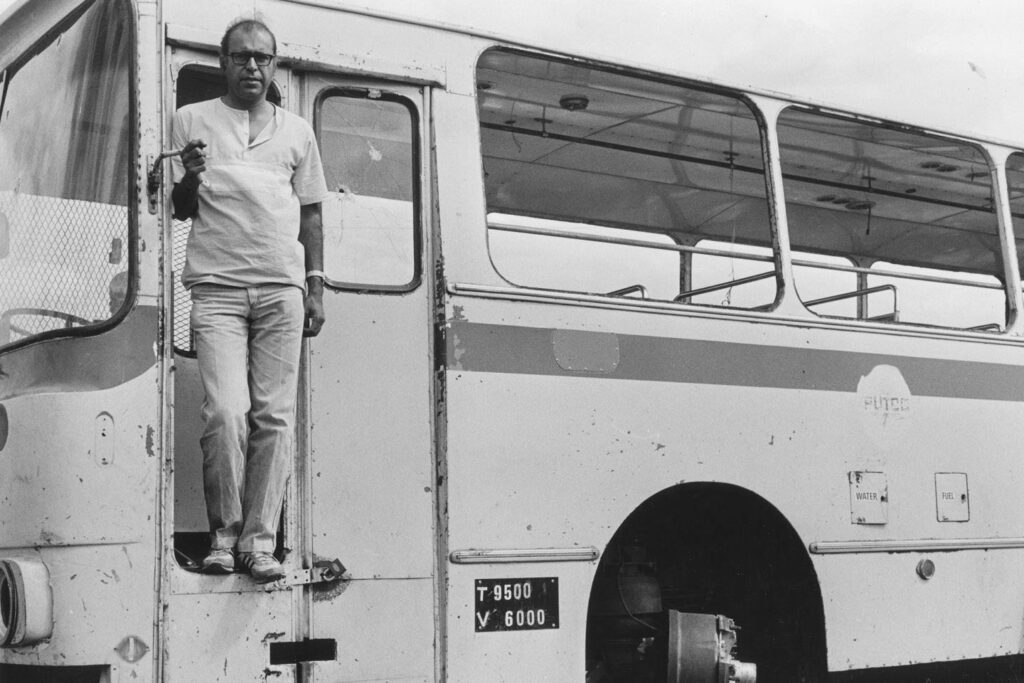

SOUTH AFRICA: AZAPO 9th Congress in the 1990s. (Photo by Gallo Images/City Press)

Earlier this year, the Azanian People’s Organisation (Azapo) and the Abu Asvat Institute for Nation Building commemorated the 33rd anniversary of the death of Abu Baker Asvat, a medical doctor and political activist. Asvat was murdered in his clinic in Soweto in January 1989.

Since President Cyril Ramaphosa posthumously conferred the Order of Luthuli in Silver on Asvat late last year, this inspiring radical activist has re-emerged in our national conversation, although not to the same extent as other important political figures outside the ANC such as Neil Aggett and Rick Turner.

The re-emergence of Asvat as a significant figure in our political memory is a hopeful sign. His modest lifestyle and selfless commitment to working with the oppressed has many lessons for contemporary South Africans.

This is especially true now, at a time when people claiming descent from the national liberation struggle have so fundamentally betrayed the political principles that guided that struggle.

But it would be a mistake to affirm the memory of Asvat as an individual without also affirming the memory of Azapo, the political organisation of which he was a part. Azapo is an often forgotten current in our radical past that, along with the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC), offers what some would say is a far more penetrating critique of colonial power and the system of racial capitalism it spawned than anything developed by the ANC.

This week marked Human Rights Day, when 69 people were gunned down in Sharpeville in 1960 for protesting against the pass laws. Robert Sobukwe’s PAC led the protest.

Sobukwe was an extraordinary human being, a global visionary and philosopher who was kept in solitary confinement for six years for his role in the anti-pass campaign, which led to the massacre. Sadly, when we observe Human Rights Day, he and the politics that carried people into the streets in Sharpeville are largely forgotten.

The PAC never regained the popular character it had forged by 1960, and in the late 1970s the primary pole of political organising and thinking outside of the Charterist tradition of the ANC would shift to Azapo.

SOUTH AFRICA – Dr Abu-Baker Asvat. (Photo by Gallo Images/City Press)

SOUTH AFRICA – Dr Abu-Baker Asvat. (Photo by Gallo Images/City Press)

Azapo was never a mass movement on the scale of the United Democratic Front (UDF), but it was once known for its intellectual and political gravitas. It was also, crucially, a firmly socialist organisation. The development of Black Consciousness into an explicitly socialist direction is another often forgotten element of our history.

The adoption of Black Consciousness rhetoric and symbols by the 2015 student movement was focused on the early years of the Black Consciousness project, which was not explicitly socialist.

Azapo, which was formed in 1978 as an explicitly socialist development of Black Consciousness, was conspicuous by its absence in the gestures of return that often marked this political moment.

Azapo did not only hold the line on a clear commitment to socialist politics throughout the 1980s. It also took a number of positions that led many to see it as an impressively principled organisation.

When the ANC promoted the idea and slogan “liberation before education” in 1985, thereby becoming complicit with the production of “the lost generation”, Azapo opposed this and the school boycotts. When some in the ANC, most notoriously Winnie Madikizela Mandela, supported the necklacing of people said to be informers — often incorrectly — in the late 1980s, Azapo opposed the practice, arguing that it showed a disregard for the lives and dignity of black people.

At this time there was also intense conflict between Azapo and the UDF, which took the form of what people at the time called a war. The UDF is often remembered as a lost opportunity for South Africa, as a mass democratic project that allowed itself to be captured by the ANC, putting an end to aspirations for a radically democratic future.

It is true that, although the development, form and character of UDF affiliates were uneven, there was, for a period, an impressively democratic culture with practices of democratic decision-making and the right to mandate and recall leaders.

But it is not always recognised that violent external hostility to Azapo accompanied this internal democracy.

Today many older intellectuals respect Azapo’s historical role, but it is not part of the political imagination of most younger people and has not had a significant presence in our politics since 1994.

Former president of Azapo Sathasivan “Saths” Cooper believes the party should have contested the 1994 election. “It lost a critical moment by not participating in the first democratic election, and Black Consciousness has failed to carry its message through,” he says.

Now Azapo is in the process of reimagining its political relevance. A new, younger leadership is more in touch with issues on the ground. In a country where half the population is under the age of 30 and most people are impoverished, unemployed and politically uninspired, a leadership that resonates with the young is a great asset. In this context, it is not surprising to see Azapo memes circulating on social media.

The new leadership assumed office in December and aims to overcome the apathy of the past. Cooper says Azapo is doing the right thing by working on local issues and aiming to support local struggles, which will serve as a foundation to rebuild the organisation from below.

“Azapo is doing what it should have been doing a long time ago — it is reaching out to others and the young leadership is driving political rejuvenation. They are aware of the problems of the past and are shedding themselves of that,” Cooper says.

“If they continue to work they will make strides. The new leadership is on the right path. Who knows, there could even be an alliance of the Left in the future — but they should not repeat the mistake of being on the receiving end of largesse. The Left should not also eat from the public purse.”

Last month Azapo and the PAC, which has also been a marginal organisation since 1994, announced a new unity pact with the intention to contest elections together. Given the scale and intensity of our social crisis, and the fact that the ANC has captured and neutralised its own Left, the political terrain is wide open for a mass-based progressive alternative.

But as we know, despite mass unemployment and a broader social crisis, Left parties have not fared well when they have stood for elections without first putting in years of work to build grassroots structures and unity across the left.

It took the Workers’ Party in Brazil 20 years to build a viable electoral project. Building a Left party here may also require a similarly long-term commitment. It would certainly require the buy-in from the unions organised outside of the ANC and, of course, Abahlali baseMjondolo, the only organisation that has been able to mobilise the impoverished people who throng our cities at significant scale.

History does not offer much hope for the new Azapo-PAC alliance. When political parties decline into tiny groups fixated on past glories, they almost never recover mass support. Nonetheless Azapo, which claims descent from Steve Biko, and the PAC, which claims it from Sobukwe, carry names, ideas and political histories that have not been sullied by the degeneration of the ANC.

If Azapo does follow through with its commitment to engage local issues and struggles, it is not impossible that it could, through the slow day-to-day and year-to-year grind of popular organisation, begin to build a popular constituency from below. But this would require a forward-looking project, one attuned to the realities of the present rather than a politics rooted in the past.

If Azapo is not able to build popular support from the ground up, which is the most likely outcome, the new alliance with the PAC could still, to some extent, create a new pole of radical opinion in a political landscape marked by crude opportunism and a rapid and worrying drift to the Right.