Leaders: (From left) UDF president Archie Gumede, unionist and UDF activist Willies Mchunu, Cosatu general secretary Jay Naidoo, unionist and UDF executive member Murphy Morobe. Photo: Gallo Images/Rapport archives

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Durban strikes, which began on 9 January 1973, and the 40th anniversary of the launch of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in Cape Town on 20 August 1983.

From the outset, the UDF aligned itself with the ANC and, by 1985, when labour federation Cosatu was launched in Durban, the bulk of the union movement came to align itself with the ANC. But neither the union movement nor the people and organisations brought together under the banner of the UDF operated as simple instruments of the ANC.

There was considerable political innovation from below and as ideas such as worker control and popular power came to the fore, a clear, if not always acknowledged, tension with the more elitist and authoritarian currents in the ANC developed.

At their best, the unions and the UDF proposed democratic modes of organisation as both means and end, saw popular democratic power as the royal road into a democratic future and were mindful that national liberation would not be well served by surrendering popular power to national elites. This has sometimes come to be concretised in two speeches.

The first, delivered by trade unionist Joe Foster in 1983, argued that organised labour should sustain some autonomy within the wider struggle for national liberation: “Workers must strive to build their own powerful and effective organisation, even while they are part of the wider popular struggle. This organisation is necessary … to ensure that the popular movement is not hijacked by elements who will, in the end, have no option but to turn against their worker supporters.”

The second speech, given by Murphy Morobe of the UDF in 1987, argued for radical or participatory democracy in the struggle and the new society to come: “We are talking about direct as opposed to indirect political representation, mass participation rather than passive docility.”

The democracy to come in a free South Africa meant “all South Africans, and in particular the working class, having control over all areas of daily existence — from national policy to housing, from schooling to working conditions, from transport to the consumption of food”.

There are many necessary critiques of the ideas and practices of the union movement and the UDF, and full measure has never been taken of the political and personal costs of the war between the UDF and the Azanian People’s Organisation that began in Soweto in the winter of 1986. But it can’t be denied that, together, the union movement and the UDF drew millions of people into organisation and struggle, built popular power at significant scale and intensity, and pushed the apartheid state into a stalemate.

After its ascent to state power the ANC moved quickly to co-opt and undo the forms of popular power that had been central to its victory, and when new and autonomous nodes of organisation emerged at the turn of the century they were repressed. Today it promotes forms of official memory that obscure popular participation in the struggles that brought it to power and prefers to build collective memory around its own mythology, including the presentation of its leaders as, in the main, great men with a singular capacity to move history.

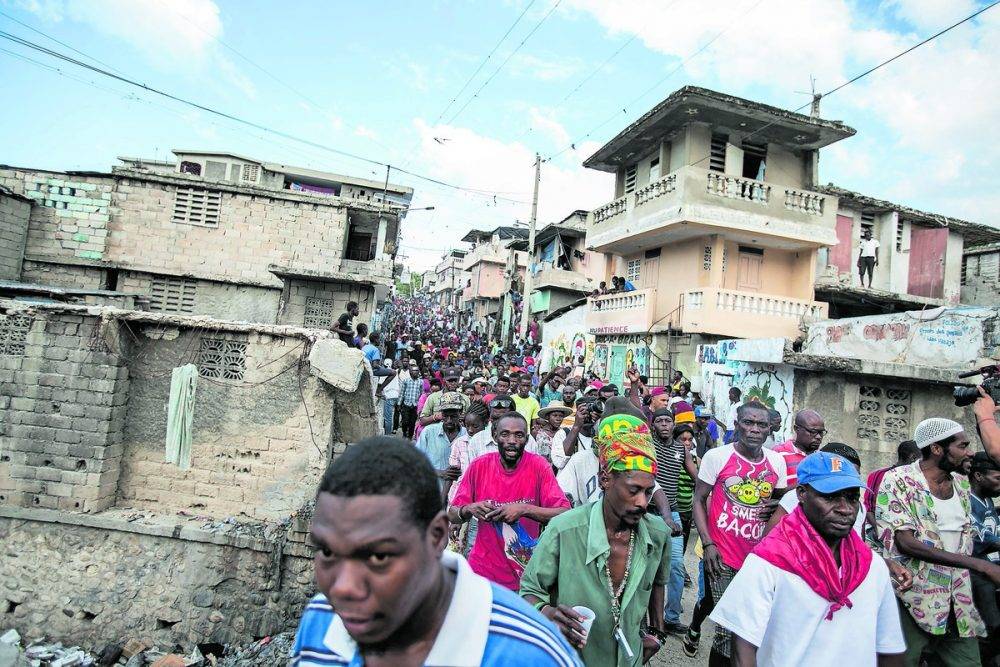

Power in the popular: Supporters of the Fanmi Lavalas political party, as it was by then known, protest against the presidential election results in Haiti in 2016. (Bahare Khodabande/Getty Images)

Power in the popular: Supporters of the Fanmi Lavalas political party, as it was by then known, protest against the presidential election results in Haiti in 2016. (Bahare Khodabande/Getty Images)

As new generations of young people have successively taken to the intellectual stage the decline in the standing of the ANC, or the version of it that came to be associated with Nelson Mandela’s trajectory after prison, has often resulted in figures like Steve Biko, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Robert Sobukwe being proposed as alternatives to Mandela.

There is real value in widening our sense of our political history, and much to learn from some marginalised currents and personalities. But replacing one great figure with another in a manner that sustains the erasure of the political contribution of ordinary people carries real political limits. There is often scant acknowledgement of the actual forms that the work of building sustained democratic counter-power takes, most notably the meeting.

The work of building popular organisation meeting by meeting is slow and patient work. It requires deeply attentive presence in the local and to the particular — to these people, this meeting, this place. It requires the humility necessary for intense and respectful listening, for coming to a shared understanding and building trust.

This kind of political meeting operates at an entirely different pace and scale to the libidinal flows moving through the nodes in the digital realm designed to both elicit and exploit emotion. As a result it may seem out of time, as a politics of a lost world. Technology changes culture and just as politics was different in Europe after Johannes Gutenberg introduced the printing press in the mid-15th century it has become different after the smartphone.

We are both atomised and connected by our phones and the velocity with which images and ideas can travel and mutate vastly exceeds anything that could have been imagined in the age of the pamphlet, the orator on a box in a square or the circulation of speeches on cassette tape.

A man sets himself alight outside a municipal office in a provincial town in Tunisia, or the police murder another young man in Paris, and in a sudden electric moment strangers are pulled together, there is a sense of an ethical life in common and, for a moment, everything changes.

The Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall, all propelled by the torsion between lived and mediatised reality, exploded into life with a scale and speed that can easily appear to have rendered what came before redundant. When they achieve sufficient intensity these moments can upend an entrenched symbolic order in days, but they seldom leave behind the kind of organisation that can continue day-to-day political work month after month and year after year.

Of course organised movements — movements with members, meetings, structures and elections — have their own temporality. When organised fidelity to a new moment is sustained beyond its initial appearance it will never be permanent. Energies dissipate, sclerosis sets in, ideals are corrupted, rivalries emerge, people are co-opted, bureaucracies form and acquire their own interests.

The one-and-a-half-million-strong movement of the landless in Brazil, the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST), which will mark its 40th anniversary next year, is an outlier.

Nonetheless, movements like the MST, and more modest projects around the world, win real gains for their members and create invaluable space for convergence, practices of solidarity and what Abahlali baseMjondolo here in South Africa call “thinking together”. They build nodes of power outside of states and enable democracy to be about participation as well as representation.

And since the turn of the century the countries in which there have been profound social advances have all been changed, from below, by the interplay of popular organisation and state power.

In Haiti the political movement that emerged against the US-backed dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier in the mid-1980s, and which came to be known as Lavalas (avalanche or flood), would survive extraordinary repression, carry Jean-Bertrand Aristide into the presidency 1991, endure a coup seven months later, return Aristide to state power in 2000, suffer a second coup in 2004 and continue to resist for many years to come.

Members of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto, the movement of the urban poor, protest in São Paulo. (Thiago Bernardes/Getty Images)

Members of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto, the movement of the urban poor, protest in São Paulo. (Thiago Bernardes/Getty Images)

Although driven from office by an alliance of local elites and the US and other Western governments it enabled impoverished people to take the political stage, affirm Haitian sovereignty and undertake significant reforms, such as the disbandment of the Haitian military in 1995, a military that had been set up by the US to oppress the Haitian people.

In Brazil Lula da Silva first came to political prominence as the leader of the metalworkers’ union during a series of strikes that ran from 1978 to 1981. During his first two terms in office, from 2003 to 2011, poverty was cut by half and more than 20 million people were lifted out of poverty.

Along with the unions he has been given critical support by other forms of popular organisation such as the MST and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto (MTST), a movement of the urban poor.

In Bolivia poverty was more than halved during Evo Morales’ term in office from 2006 to 2019, 54.2 million hectares of land were redistributed and illiteracy eradicated. The origins of the Movement for Socialism, the party that brought Morales to power, lie in unions, indigenous, peasant and urban movements, and a series of political ruptures, most notably a popular uprising against water privatisation in late 1999 and early 2000.

In each case there were real limits to what was achieved, and there are all kinds of important critiques of all these presidents, their parties, the governments they ran and the movements that backed them. Although things could have been better, the contrast with our own trajectory since the end of apartheid is instructive.

This does not mean that we can or should try and go back to older modes of politics. Politics takes specific forms in particular historical moments, and periods of innovation are always limited and often brief. Those who seek to mechanistically impose ideas and practices extracted from the past onto the present can only, to borrow a phrase from Frantz Fanon, “come down into the common paths of real life … [with] formulas which are sterile in the extreme”.

But there is a real way in which the people, as a collective force, were stronger in 1980s than they are now, and we know from Haiti, Brazil, Bolivia and elsewhere that the work of building progressive movements, meeting by meeting, year by year, remains the best route that we have into more just futures.

We would do well to give our remarkable history of popular organising its due in our historical imagination, and to understand the urgent necessity for new forms of popular organisation in the present, if we are to make some progress on the hard road that lies ahead.

Richard Pithouse writes about politics, music and poetry.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.