Equality: Members of the United Democratic Front were of all hues, but were they truly non-racist? Photo: Gallo Images/Rapport archives

I was 20 years old in 1991 when I fell in love for the first time. She ticked all the boxes; she was beautiful, progressive and believed in building a non-racial, non-sexist and united South Africa. Her family were well-known supporters of the struggle against apartheid.

But our relationship was doomed because her family was against us being together. I was dark-skinned, not Gujarati-speaking and poor. Her family told her that if she continued to see me, they would deal with her. I knew this was going on while her family attended ANC meetings and hypocritically called for equal rights and the end of racism and prejudice.

Unfortunately this traumatic experience is not an anomaly in the Indian-origin community I belong to. It happens more often than not. Colourism, where the fairer of complexion you are, the more you are appreciated, runs deep in this community. Divisions based on religious language groupings are strong.

The majority of Gujarati and Urdu-speaking people came as “passenger Indians”; they paid their own passage to South Africa and were free people. Those who were Tamil and Telugu-speaking came mainly as indentured labourers, and were ostensibly poor and working class.

Gujarati and Urdu-speaking people originated from the northern parts of India, and therefore were fairer of complexion.

Black African people in South Africa are accused of “reverse racism” and we correctly caution of a rising exclusive nativism in the black African community. For there to be progress on the national question, the focus cannot only be on black African and white people. We have to call out the entrenched racism in the so-called Coloured and Indian-origin communities.

To put this into perspective, generally there is the racism that people of Indian origin practise against each other, and there is racism and enmity between so-called Coloured and Indian-origin groups. But both groups do not care for people who are black Africans; they regard themselves as superior. Yet both, as much as they claim to hate white supremacy, still regard white people as the pinnacle of the racial food chain.

I recall driving as a young family with my former partner, who was so-called Coloured, to Durban for a weekend break. As we approached Durban, I told her to brace herself. I cautioned her that people, especially so-called Coloured people, would look at her strangely because she was with a person of Indian origin.

So-called Coloured people in Durban are a minority, quite snobbish and look down upon people of Indian origin. I added that people of Indian origin would either admire me for being with a so-called Coloured woman or despise me because they would presume I thought I was smart for being with her. And I said that if the staff at the hotel were of Indian origin, they would have difficulty serving me because they were used to serving white people.

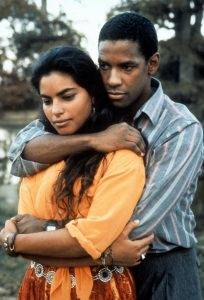

Not only black and white: Sarita Choudhury and Denzel Washington in a scene from ‘Mississippi Masala’. Photo: Samuel Goldwyn Company/Getty Images

Not only black and white: Sarita Choudhury and Denzel Washington in a scene from ‘Mississippi Masala’. Photo: Samuel Goldwyn Company/Getty Images

She dismissed my concerns, thinking that I was talking nonsense. But that evening, when we went out to buy takeaways, she experienced everything I warned her about. And the next morning at breakfast, whenever I tried to wave a waiter over, there would be no response. But the moment she lifted her hand at least two would rush over.

There is a general elitism, racism and prejudice against darker-looking and working-class people in these communities that is normalised and an acceptable social practice.

In more than one relationship with a so-called Coloured person, their parents refused to accept the relationship because I was of Indian origin. I was referred to as a “coolie”. We were adults and working professionals, as were the parents, who claimed not to support apartheid and its backward values.

Mississippi Masala is a 1991 film about a family from India who re-settled in the US. Denzel Washington plays the role of Demetrius, an African American who works in the family’s carpet cleaning business.

In one scene, the uncle of Indian origin says to Demetrius, “There is only black and white, nothing else. We are the same, me and you.” I have heard that statement so many times in my community, not just among family but also in every type of social gathering from drinking holes to religious gatherings. But, when Demetrius began a romantic relationship with their niece, suddenly it was no longer “only black and white”.

So as we romanticise our memory of the United Democratic Front (UDF) and its seemingly non-racial character while surreptitiously calling out the ANC — and especially the black African majority — let us not fool ourselves. Our communities are generally racist towards each other. The more black African you look, the more racism you experience.

The UDF’s non-racialism is a myth. It gave the impression that it was non-racist because it made certain that so-called Coloured people and people of Indian origin felt in charge, even if the communities they came from were havens for racism and elitism.

We will not be able to build a non-racial country if we do not confront the entrenched racist practices in our communities. We are quick to call out others, but fail to be honest about how easily we retreat to our racial laagers. Romanticising the struggle against apartheid is not enough to defeat the values of it. We have to build a country where racism is truly unacceptable, not only when you think of yourself as the victim.

Donovan E Williams is a social commentator.