Former Brazil president Dilma Rouseff turned to austerity, but it was too late. (Photo by Mario De Fina/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

More than three decades ago, two Italian economists, Francesco Giavazzi and Marco Pagan, planted a very dangerous idea: that fiscal austerity has the potential to generate economic growth, rather than drive economies into recession.

In their 1990 paper, Can Severe Fiscal Contraction be Expansionary? they considered the so-called “German view” of fiscal policy, which suggested that, in scaling back the public sector, austerity would create more room for the private sector.

This view coincided with a growing acceptance that the state was not capable of bringing about economic growth needed for development — and indeed that “big government” would end up crowding out corporate investment.

This idea’s danger lies in it having propped up the private sector and clearing the way for corporate capture, while simultaneously infantilising the state. And this view would have a profound effect, including on the budgets of various countries, which would be left with almost no space to grow.

In a report published last week, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development took up this very subject.

The report points to its 2010 edition, which warned about the “draconian fiscal retrenchments” inflicted in Europe in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. The fiscal adjustment programmes post-2008 were adopted under the guise that spending restraint would make economies more resilient towards other market-induced shocks down the line. This as some governments grappled with higher debt.

“In the eagerness to embark on fiscal consolidation, it is often overlooked that a double-dip recession, through its negative impact on public revenues, could pose a greater threat to public finances than continued fiscal expansion, which, by supporting growth of taxable income, would itself augment public revenues,” 2010 Trade and Development Report noted.

In its 2023 report, the UN’s economic arm reflects on a more recent crisis: the economically devastating pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

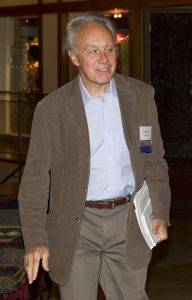

Italian economist Francesco Giavazzi planted the idea that fiscal austerity has the potential to generate economic growth, rather than drive economies into recession. (Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Italian economist Francesco Giavazzi planted the idea that fiscal austerity has the potential to generate economic growth, rather than drive economies into recession. (Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

In the pandemic’s wake, growth in most G20 countries is still much lower than it was in the 2010s, according to the report. But primary fiscal balances — the balances that exclude interest payments and which are, therefore, the more easily controllable parts of governments’ budgets — have quickly turned positive. “This largely results from the high pressure faced by governments to reduce deficits to continue to have access to international credit markets,” the report notes.

This pressure to inflict austerity, which South Africa is all too familiar with, has been proven to exacerbate boom-bust cycles and diminish the desired effect from emergency stimulus. Meanwhile, as the corporate sector gets its claws in, the state loses its ambition to shape the economic trajectory, including through fiscal policy, and tackle heightened inequalities.

At the same time, the growing concentration of market power by large corporations and influence of high net worth individuals reduces the state’s ability to raise tax revenues, according to the report.

“In an era of compounding crises that increasingly require public resources to address systemic disruptions, the asymmetry between growing corporate consolidation and the thinning fiscal space need to be addressed by revisiting dominant economic paradigms and, critically, the policy decisions based on them,” the report concludes.

One of the implications behind austerity is that the state is incapable — or too corrupt — to effectively manage its resources. Under this pretence, the private sector becomes the more acceptable instrument for creating economic growth. The government is relegated to being merely a referee.

But, as with most things, the truth has proven to be far more complicated. The private sector’s blue-eyed boys most often turn out to be as, if not more, tainted than the state. And, critically, they have tended to fail to achieve their growth mandate — leaving the public sector in a far worse fiscal position than if it were to assume expansionary policies.

In an article published last week, economists Clara Zanon Brenck and Pedro Romero Marques look at the evolution of fiscal policies in Brazil, a country which bears certain political and economic similarities to South Africa.

Like South Africa, Brazil enjoyed a commodity-driven expansion in public spending from the early 2000s to the mid-2010s. This period coincided with Lula da Silva’s first term as president.

But, during Dilma Rouseff’s presidency, Brazil’s fiscal position deteriorated markedly, thanks in part to the global slowdown post-2012. Instead of stimulating the economy through expanded public spending, Rouseff’s government did so through tax breaks, hitting revenue.

Amid waning credibility, and with the economic elite turning on the government, Rouseff turned to austerity. But it was too late. In August 2016, she was impeached — a development which marked the fall of the Workers’ Party, clearing the way for the far-right, as well as intensified austerity.

And even with Lula’s return, the fiscal policy debate remains dominated by pro-austerity orthodoxy, according to Brenck and Romero.

Under the congress-approved Sustainable Fiscal Regime, the state is constrained, even in economic booms. This, the pair argue, “limits the government’s ability to participate in the long-run growth plan … ceding ground to the private sector”.

“Fiscal rules claim to insulate fiscal policy from political influence,” the article concludes.

“But this is its own form of politics: constraints reduce the space for the working class, whenever in power, to influence fiscal policy decisions and pursue redistribution.”

The choice to adopt austerity is not about protecting the state against capture — nor is it about realising untapped growth, as evidenced by South Africa and other economies for about a decade now. Instead, restrictive fiscal policy eats away at state capacity, leaving more room for the corporate sector’s corruptive power.

As the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) has recently pointed out, South Africa’s fiscal position will not improve without growth, needed so that the government can sustain a larger debt stock. The state needs to incur debt to sustain aggregate demand and make the necessary investments that underpin economic expansion, the IEJ explained.

Among other things, the IEJ proposes that the government raise additional revenue in the short-term by removing tax breaks for high-income earners and corporates, as well as increasing taxation on wealth and income from financial assets.

Taking these steps requires political will — and a state which refuses to be swayed by narrow interests.