Only a collective response will ensure water security and the per person use to a below a 170-litre future

Many places in the country already experience a Day Zero, frequented by water-shedding, interruptions, low pressure and long shut-downs for maintenance.

In addition, there is sufficient evidence that South Africans’ water usage is not sustainable for a water stressed environment. Our per capita water usage is way above the world norm of about 170 litres per capita (person) per day — in Gauteng this averages about 270l/cap/day.

Thus, municipalities need to develop innovative programmes that manage household and industry water demand as a priority and with urgency.

Traditional water responses centre on engineering and new infrastructure. This approach is relevant where areas have not established baseline water security, but in already well-serviced areas this approach seems to create perverse behaviour to consume more.

Demand strategies (outside of crisis periods) have tended to employ price, pressure management or information and awareness campaigns, individually or in combination, to limit people’s water use. But very little to nearly negligible attention is afforded to long-term behavioural change, which can have a longer lasting and sustainable effect on water security.

In an environment of growing water constraints and risks, water use behaviour and value is a crucial intervention requiring effective adaptation and mitigation strategies. People have to be part of dealing with water problems, including the aspects that climate change brings. The value of every drop of water needs to be on everyone’s conscience so that they are part of the solution. Collectively we have to aspire rapidly to a below 170 litres per person per day future if we want better water security and economic growth.

Innovation in this area should be encouraged because it holds the promise for water demand management. One such option are behavioural nudges (messages), which have been found to be an effective way to promote pro-environmental behaviour. In the context of water and electricity, these interventions signal a departure from the instruments typically used to elicit behaviour change — price interventions (tariffs and taxes) and structural interventions ( water restrictions and load-shedding).

The behavioural change approach is based on behavioural economics by expanding the classic model of rational human decision-making and allowing for the various biases and positions that characterise people as they really are. This is helpful for policy design. The benefits of this approach is that it has the ability to produce policy interventions that “nudge” people into a behaviour that is in their best interests, but which they, for some reason or another, do not adopt.

It involves techniques that influence or trigger two aspects of human behaviour, norms and salience. Behavioural change techniques were used during the Day Zero crisis in the City of Cape Town, through its billing system. It is about providing consumers with sufficient information and knowledge to link to their own water use, as well as the broader water issues.

Behavioural “nudges” augment conventional economic theory by also using insights from psychology to give a better understanding of human decision-making. It strips away the theoretical assumptions that people always act rationally and have the computational ability to carefully evaluate all choices by comparing current and future cost and benefit streams. Behavioural nudges can be used to identify circumstances where people show poor judgment or don’t act rationally (for example, deferring saving or wasting electricity).

An example of a behavioural bias that can be leveraged to better design policy is the lack of full information to inform the consumer.

People have limits either to information or to the cognitive ability to make decisions based on full information. In the context of water consumption, it is difficult to conceptualise, for example, how six kilolitres — the amount allocated free of charge water — translates into the amount used for cooking and bathing in one’s household. An example of a tangible reference point we have for one litre is a container of milk. But translating a one-litre container of milk into an amount of water consumed for various uses in a home is not easy (even for those with high cognitive ability). Thus, when households receive their water bill, it is probably unclear how they can reduce their consumption in kilolitres of water.

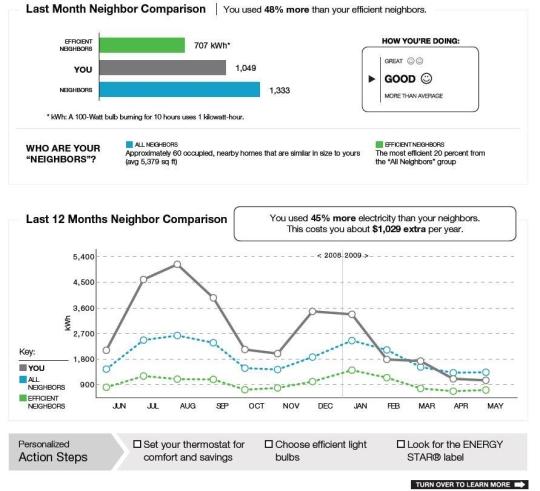

In addition to improving communication about the level of consumption, information could also be used in the form of making consumers aware of how their consumption compares to that of their peers. Insights from psychology emphasise that we often care about what our peers are doing. Social norms signal appropriate behaviour in a group. We behave in ways expected of us in case there is a negative social consequence to violating the norm. Thus, pro-social behaviour can be encouraged by making social norms more explicit.

Inexpensive, non-price and non-regulatory based behavioural interventions are increasingly being seen as a way to promote pro-environmental behaviour. They form part of the mix of interventions but are a crucial long-term intervention if the connection to water use and the value of water to water problems in South Africa are to be realised.

Jay Bhagwan is an executive at the Water Research Commission.