Visitors leave on May 19, 2010 the Apartheid museum in Johannesburg, South Africa. The Apartheid Museum opened in 2001and is acknowledged as pre-eminent museum in the world dealing with 20th century South Africa, at the heart of which is the Apartheid story.The Apartheid museum, the first of his kind illustrate the rise and fall of Apartheid.

The exhibits have been assembled and organized by a multi-disciplinary team of curators, filmmakers, historina and designers, include provocative film footage, photographs, text panels and artefacts illustrating the events and human soties that apart of the epic saga known as Apartheid.

Transformation: A visitor at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. The seven-year gap between the author’s first and second visits to the museum entirely changed his appreciation of it. (Gianluigi Guercia/AFP)

We’re all familiar with iconic pictures from the first democratic election 27 years ago. They capture people queuing in the form of a river, twisting and turning into shapes previously unseen in South Africa.

These queues stand in contrast to the rigid history of white supremacy — of black and white, us and them — and created shapes that cut across the historical narrative of racism and separation in the country.

Some people feel it’s pointless to contemplate freedom in South Africa because the topic is just window dressing for the most unequal country in the world. Some overlook the violence of the transitional period. Others feel the topic is redundant and everyone should just move on. Perhaps it’s even less useful for an American like myself to do so. What can an American illuminate about South Africa’s democracy anyway?

But I do think it’s necessary to reflect on South Africa’s transition, especially as a non-South African, because I believe the outcome of democracy is revolutionary.

It’s crucial to continually reflect on South Africa’s transition to democracy, no matter who is doing so because the significance of it changes and evolves over time — it doesn’t and shouldn’t mean one thing.

When viewed in relation to the full extent of South Africa’s turbulent history, the outcome of democracy is so unlikely.

Although it’s tempting to adopt an insider-outsider perspective as a non-South African, preferring to consider differences between “here” and “there”, establishing my life in South Africa has required me to adopt as full and as wide a view of the country as possible.

When it comes to South Africa’s history, this means not considering only apartheid, but also the projects of slavery and colonialism. These projects are too often thought of in historical silos, even though they built off one another.

But, I didn’t always think about South African history this way. In fact, for some time I had a skewed view of it.

In 2011 I visited the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. I was a wide-eyed international student originally from Minnesota, in the US, and had spent a semester at Stellenbosch University. At the time I was an undergraduate student at the University of Kansas.

What I remember from my first visit to the museum was the brutality of apartheid depicted throughout the different exhibitions: the tragic combination of violence, fear and ignorance that was institutionally diffused across South Africa.

My first impression of the museum — and, by extension, South Africa’s history — wasn’t shaped by understanding. It was instead shaped by the ease with which a visitor like me could conveniently cordon off the apartheid past, as if continuity between then and now were a figment of some imagined present. What the museum depicted was history, after all — and it was not my history, I assumed.

Seven years later, in 2018, I visited the Apartheid Museum for a second time. This time I was working with a group of American international students studying at the University of Cape Town.

During my second walk through the museum with American students in 2018, I had an entirely different and altogether profound experience. I came to realise how mistaken I was to assume South African history was not my history and, had, in fact, become a part of my life since my first visit. What made my second visit profound was all that had happened in between.

My life had transformed. I returned to South Africa, in 2013, after finishing my undergraduate studies to pursue a postgraduate degree at Stellenbosch University, focusing on Marlene van Niekerk’s novels Triomf and Agaat. I started working with international students. I also met the woman who became my wife in 2017.

Over time, a path opened up and I saw my future in the country.

With this backstory in mind I walked from display to display in the Apartheid Museum during my second visit and realised that, had the transition to democracy in 1994 failed or descended into violent civil war, as it almost did, I wouldn’t have met my wife and the contours of my life would be radically different. As this realisation took shape I stood before a map of the Bantustans, which had truly become legible to me.

One of the few towns listed on this map was where my wife is from. Realising all that had to happen — both in the US and South Africa — for us to meet, I was moved to tears.

Leaving the Apartheid Museum that day I realised I wasn’t in between South Africa and the US. I was leaving not only the US behind, but also my initial understanding of South Africa and its history.

I was learning to see the country with a fuller view of history that considers how the present was shaped by centuries of racism and subjugation through the projects of slavery, colonialism and apartheid.

When considering South African history, many people unfortunately overlook the extent to which slavery, with legislation like the Cape Slave Law, shaped parts of the foundation of society. From 1658, when the first group of human beings used as slaves arrived on the Amersfoort, to 1834, when it was abolished in the Cape Colony, slavery was prominent. That’s 176 years — or the amount of time between 1834 and the 2010 Soccer World Cup.

Although colonialism began in 1652 with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck and the Dutch East India Company, the period after the abolition of slavery saw the expansion of a colonial mindset.

This period encouraged land dispossession and reinforced the legislative infrastructure first imposed during the project of slavery with laws like the Native Lands Act, or the Immortality Act — which would have made it illegal for my wife and I to be together — helped to advance a system of racialised paranoia and neglect.

When the National Party took over in 1948 and implemented apartheid, they inherited an infrastructure of white supremacy. Despite the intrinsic illegality of apartheid, one of the most poignant displays at the Apartheid Museum is a collection of the different laws that made up the system.

Although the number of laws illuminates the extent to which South Africans always resisted oppression, upholding the legality of white supremacy requires many “laws”. There’s no morality in such a system, so governing parties need to try to legislate away any sense of moral conviction.

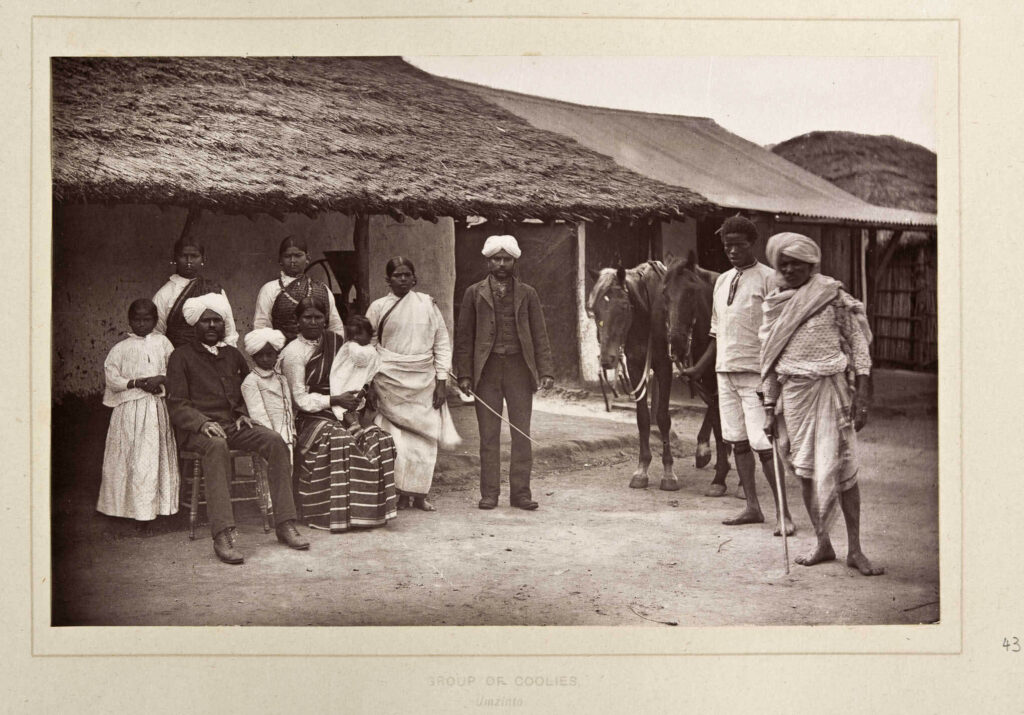

Cycles of history: An Indian family in Natal circa 1888. The indentured labour Indian people were subjected to at the time was a form of slavery, which, together with colonialism, greatly influenced the construction of apartheid. (The Collections Library of the South African parliament)

Cycles of history: An Indian family in Natal circa 1888. The indentured labour Indian people were subjected to at the time was a form of slavery, which, together with colonialism, greatly influenced the construction of apartheid. (The Collections Library of the South African parliament)

The belief that South Africa belongs to all who live in it is revolutionary because, for more than three hundred years, through the projects of slavery, colonialism and apartheid, South Africa was designed — in many ways, violently so — to fail.

So, overcoming this history in 1994, after negotiations and a democratic vote — in a country that preferred violence to talking, and restriction to participation — is worth celebrating.

Whether the transition was revolutionary isn’t a redundant topic — there’s major historical significance at stake. Instead of thinking in terms of singularity — of what South Africa was — the future opened up to a plurality — of what South African could be.

The blossoming of possibility engendered by democracy — in a country in which, historically, possibilities were fixed, limited by race and legislated to remain in place — constitutes a major revolution.

This belief changed the lives of South Africans; it also changed my life. The courage and sacrifices of South Africans to fight for a better life and future not only made a new country possible, they made what my life has become possible.

The country changed in 1994 because people believed it could change, and they believed it was worth changing. We cannot change something that we do not believe is capable or worthy of changing.

Without knowing it and before moving to South Africa in 2013, the shape of what my life was to become was determined by people and events in South Africa, many of which took place before I was born, far away from the US.

Looking back to my first visit to the Apartheid Museum I realise it was a mistake to assume South Africa’s history couldn’t be my own. History, whatever our perception of it, doesn’t easily conform to the shapes we wish it would. It has a shape of its own, like the shapes of people queuing to vote in 1994.