The past weekend’s ANC conferences proved a major boost for Ramaphosa presidency of the party

At its heart this work seeks to demonstrate that the serious social crisis we have today in South Africa can be traced back to the fundamentally false understanding and analysis of our society and its history by the ANC, from the time of the Cape Colony and especially since the mineral revolution of the 19th century.

It is because of such a fundamentally false or mistaken understanding and analysis of our society and history that there are serious problems and limitations not only in the realm of analysis but more importantly how that informed the programmatic deficiencies in all the major documents the ANC produced, either on its own or jointly with other organisations, such as African Claims (1943), the Freedom Charter (1955), the Reconstruction & Development Programme (1993) and the South African Constitution (1996).

But it is at a theoretical level that the failure to both know and understand the kind of capitalist society already existed by the time of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, which is captured best in the critique of colonialism of a special type, which originated in the Stalinist Third International or Communist International (Comintern) 1928 conference, under the theme of the Colonial Revolutions. As further discussed in chapters 3 and 4, the Comintern, out of a combination of ignorance of South Africa and the counterrevolutionary role it began to play from the mid-1920s onwards, after the death of Lenin and under the leadership of Joseph Stalin, made this false theory plausible to both the ANC and especially the South African Communist Party (SACP), with which it is most associated.

But I do state in the conclusion what I think are the things we would need to urgently address to give sustainable hope for the future, without which I predict we are going to descend into an uncertain and chaotic future, in which unresolved and combustible race related issues, especially those which intersect with resources and social justice narratives, will feature prominently. What forms that will take is uncertain, but what is not uncertain is that our collective future will be seriously compromised and imperilled as a result, unless we urgently address the root causes of the crisis.

With the impending floodgates of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) opening upon South Africa, that future will in fact be far more imperilled, especially for black workers and youth, who already are in the doldrums of unemployment, poverty and related social miseries. Not just for South Africa, but for the entire world, especially the “Third World”, that future looks bleak, unless our leaders do what Angela Davis said many years ago: “To be radical means to seize things by their roots.”

My aim is to provide an understanding of what has really happened in South Africa, both before and after 1994. I explore the major historical developments since the days of the old Cape Colony up to 1994, when we had our first democratic and non-racial elections. It is a remarkable and revealing fact that since 1652, when Jan van Riebeeck arrived at Table Bay, up until the 1994 elections, black people in South Africa were not only largely denied the right to vote but also subjected to an avalanche of overtly racist legislation that controlled every aspect of their lives. There is no other country in the world where black people were so totally dominated, oppressed, controlled and exploited. Except for the qualified franchise in the Cape, until it was abolished in 1936 for Africans and for coloureds in 1956, that was the situation of black people in South Africa.

Afrikaner history has fascinated me, to the extent that I did some research on Van Riebeeck and the men who docked with him at Table Bay in April 1652, where they came from and what Dutch society was like in those years. Were they already racists when they arrived or did they become so after their arrival? Was there racism in Dutch society and other European countries at that time, before the contact they made with the Khoi and San? Did the fact that Spain, which had for long colonised Holland, influence the latter in its own later colonisation of many countries, including South Africa?

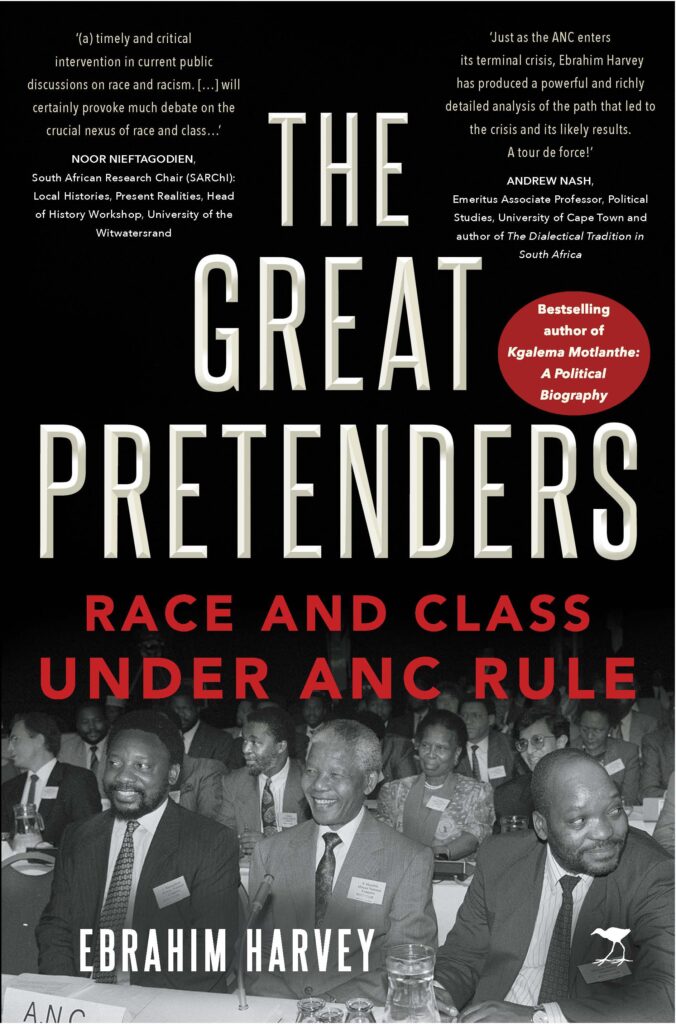

I deal with these issues in chapters 1 and 3. Though it is Portugal which first made contact with the Khoi and San, it appears that they probably learnt much about race and colour from their Spanish neighbours. Finally, the deeper I went into the study the more fascinated I became with the colonial history of South Africa, but also with the historical and global origins of race and the state of Dutch society before Van Riebeeck arrived in the Cape in 1652. There are ideological and discursive links over centuries from the early emergence of race and racism in antiquity, to early modern Europe, and also in India. Those links not only fascinated me but demonstrated beyond the slightest doubt that the race and racism discourses that have exploded in South Africa over the past few years have sorely but understandably lacked the knowledge of just how complex, complicated, ambiguous and contradictory race and racism phenomena are in fact, and that the woeful ignorance and confusion on social media left much to be desired.The Great Pretenders: Race and Class under ANC Rule is published by Jacana Media