Employers affected by the recent unrest in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal will be able to apply for support through the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) as soon as next week. (Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP)

During the recent unrest, the government resolved to deploy the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) to assist the over-stretched South African Police Service (SAPS). This joint deployment is a necessary immediate response to the lawlessness and disorder. But it is not a sufficient response to the social, political and economic problems of poor governance that has festered for well over a decade. Resolving these requires a more nuanced approach.

Systemic interventions and a higher level of accountability by state institutions are the much-needed solutions that will lead to good governance, which is fundamentally about ensuring that public resources are managed and distributed in a way that enhances the welfare of a broad swathe of citizens.

The seeds of discontent

The complex interplay between structural, economic and political factors has driven domestic fragility to this point. Profoundly different social and spatial structures are a permanent feature of contemporary South Africa. This difference is pernicious because it reinforces inequality and disproportionately benefits the wealthy few.

The Gini-coefficient, measuring relative distribution of income, reflects that South Africa is the most unequal society in the world. About 55.5% of the population is living in poverty. That is more than 30-million people. Perhaps most concerning of all is that 63% of the country’s youth are unemployed.

The government’s performance towards achieving societal transformation — the promise embedded in our democratic transition — has been deteriorating. The result is that we have failed to attain inclusive development. The somewhat justifiable economic sources of discontent have grown unabated by any sustained source of hope.

The Covid-19 pandemic has occurred in a context of pervasive inequality, unemployment, widespread poverty, food insecurity and starvation. The resultant lockdowns and mismanagement have worsened people’s conditions and prospects for material development. Interventions in the form of grants and reliefs have been minimal and temporary, thus insufficient in mitigating the economic impact of the pandemic.

Political factors have led to a persistent decline in governance performance and a growing inability to meet essential public needs and demands for services. This decline is most apparent at the local level of government within municipalities. The core impediments stem from limited capacity, maladministration and mismanagement, which leads to wasteful expenditure and corruption. The conflict with the public interest is amplified by perennial problems of the lack of accountability and meaningful avenues for political participation. These issues fuel disengagement and lead to a decline in public trust, alienating communities from state institutions.

Multilevel factors are valuable explanations of the chaos witnessed readily through the disruptive and violent nature of the looting. As an increasing segment of the population comes to regard looting as more effective than peaceful protest, this pattern of violence and accompanying disruption might become an increasingly acceptable and normalised method of mobilisation. This is likely to generate intensified and prolonged unrest in the future.

Protest, populism, polarisation and a ‘third force’

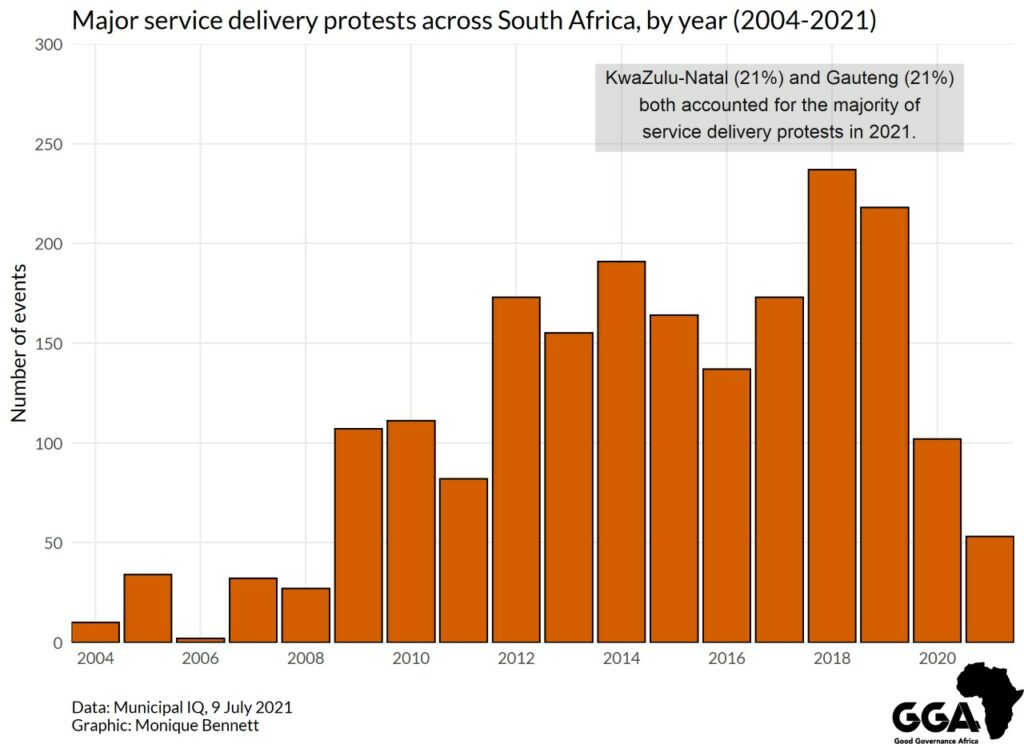

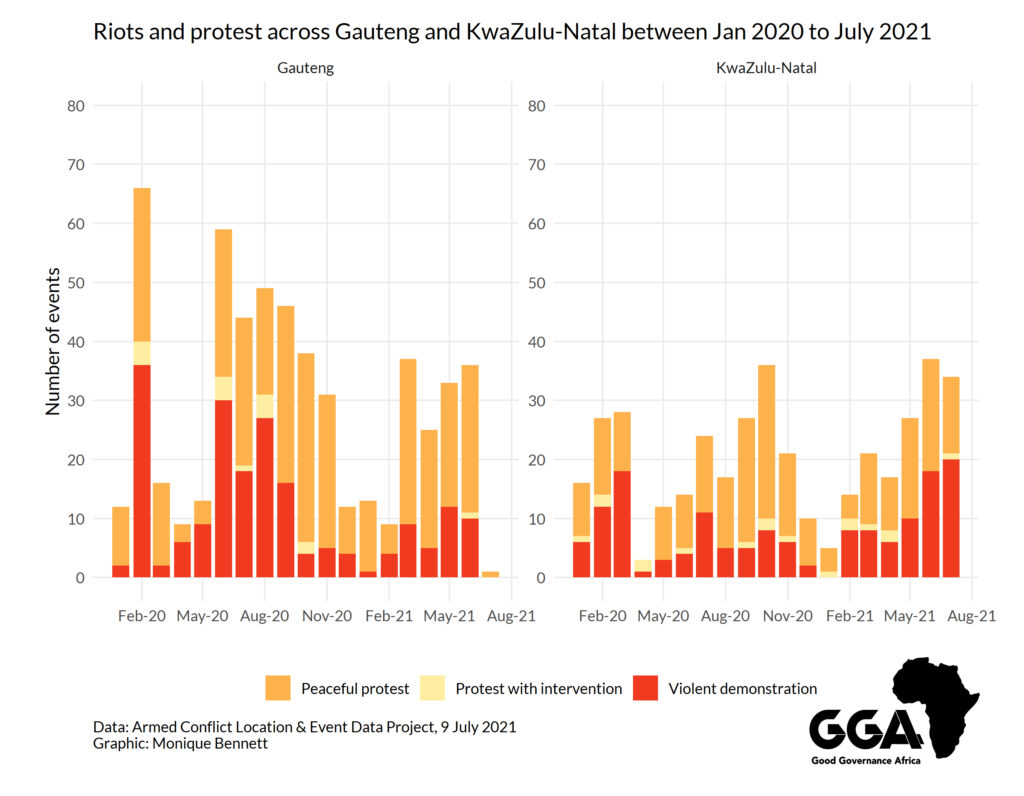

Alarms should have been heeded from the growing wave of service delivery protests, which have become commonplace in the past few years of South Africa’s democracy. These events bear a resemblance to the country’s history, particularly the extensive struggle for liberation. In the past, waves of protests highlighted disillusionment with the exclusionary and securitised nature of apartheid society. As opposed to merely being a discrete set of events, present-day violence is a broader process. The full scale of the protests has not been captured; historic data as illustrated by both the ACLED and Municipal IQ data (see below), which points to how the current outbreak did not happen in a vacuum.

It is no coincidence how they occur near predominantly poor urban areas, in townships or more informal settlements, which are protest hotspots. The inhabitants of these areas feel the brunt of exclusion from social, economic and government benefits. They are contending with ongoing struggles for essential services and limited fruitful discussions with state officials. Of major concern is how genuine grievances are now stoked by polarising discourse and exploited by nefarious forces for narrow political ends.

Cleavages along ethnic and tribal lines have been a perennial feature of South African life that have bubbled under the surface of daily existence. Historically, they resulted in extensive violence between 1990 and 1994 in parts of KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. In the present day, the late Zulu monarch King Goodwill Zwelithini’s inflammatory statements also fuelled xenophobic tensions. This led to spates of violent attacks against foreigners in KwaZulu-Natal and other parts of the country between 2008 and 2019.

Before invoking talk of “war” in communities, such as the series of tweets by Economic Freedom Fighters leaders proclaimed, or baiting violence along ethnic, class and tribal lines, politicians and other influential actors should provide more precise communication to quell the situation, exercise due caution and consider the national and local context.

Undeniably, Jacob Zuma is a polarising figure, who enjoys a distinct and widespread support base. In the days leading up to his arrest, extensive political rhetoric in various shapes and forms was employed to mobilise Zuma supporters, largely using the Zulu nationalism card for drawing support. A standout warning was the threats of violence in Nkandla by the Umkhonto weSizwe Military Veterans’ Association, the erstwhile military wing of the ANC, also seen in the threatening conduct of amaButho-Zulu regiments, the issuing of threats and flaunting and firing of weapons by the crowds, among other tell-tale signs. Inevitably, Zuma’s arrest proved the catalyst for the widespread violence and looting that followed.

Into this explosive mix, some organised and sophisticated criminal groupings are exploiting the chaos for ulterior ends. Genuine discontent is being hijacked to threaten property, life and livelihoods. Moreover, it has spilled over to disrupt societal order and the security of the country. The latter has been illustrated by the blatant sabotage targeted at vital economic zones along the N3, and the alleged threats to strategic roads, fuel, water, electricity, and communications infrastructure, which have the markings of a well-planned insurrection. We have also seen the adoption of vigilantism and self-protecting groups morphing into quasi-paramilitary groupings, which can easily spiral out of control. Combined, these factors pose a risk to the maintenance of values on which post-1994 democratic South Africa was built.

The costs of violence: a decline in business activity and investments

Townships have remained largely untransformed since 1994; moreover, there are many parts of semi-urban areas that are decaying. Decay of critical infrastructure such as water, sanitation, electricity networks and roads characterise these areas. Public violence, which targets crucial infrastructure and businesses, may reverse any service delivery gains while also deterring much-needed new investments in these areas. In addition to poor governance and lack of service delivery, businesses must now consider the risks of being targets in the expression of discontent. In turn, citizens will feel the brunt through losing employment opportunities, a reduction in formal and informal economic activity, development and reduced investments in crucial infrastructure.

What can be done?

There is a need for a nuanced approach to resolving the violent situation, particularly moving away from a security-centric approach towards effecting good governance. Some measures which can be adopted include:

- In responding to the violence

In instances where discontent inevitably escalates into violence, several considerations ought to be made.

- Strengthening the effectiveness of SAPS and interventions on crowd management – At the core of these should be introspection on the roles and functions of personnel. The criminality witnessed may elicit the attempted justification of a highly repressive response on the part of the state, which includes heavily violent policing measures to enforce law and order and stability. It is imperative that these become driven within a rights-based approach whose primary consideration is the value of human life and maintaining law and order.

- Managing the domestic deployment of the SANDF -The principle of primacy of civilian governance has correctly inculcated a culture of reluctance to use the military as a means for domestic law enforcement. This is paramount to averting loss of life in similar fashion to the death of Collins Khosa. This is essential as the unrest and protest have not metamorphosed into a national insurrection.

- Improving the effectiveness of state intelligence agencies – The deteriorating effectiveness of intelligence services must be addressed to effectively perform their primary role of gathering and practically analysing information on threats to national stability and the constitutional order and thwarting them. It should provide early warning signals and develop avoidance and preventative measures to avert the escalation of situations.

- Towards improvement of the delivery of services in the long run

Beyond the crisis and with a view to the upcoming local government elections, there is a need for a radical review of the social contract and a systemic change in values. Commitment to anticipatory governance will be vital to address the root issues.

- The implementation of intervention programmes aimed at socio-economic reforms – This is necessary and must be driven by an imperative to improve the quality of life and addressing the developmental backlogs of those who reside in informal settlements and other nodes characterised by exclusion.

- There is a need for greater emphasis on the transformation of spatial structures and settlements – Proactive responses here including improved spatial, infrastructural, and developmental planning. This will mitigate the strain, create a conducive climate for land-use efficiency, and provide innovative housing and settlement solutions.

- There must be a drive to stimulating investment and growth in the local economy – This will ensure that these areas are not reduced to a permanent state of underdevelopment. There is shared value in partnership for government, businesses, and citizens.

- The appointment of competent civil servants – This must be accompanied by an emphasis on continuous improvement of skills, which will create effective responses to the evolving demands of public service. These must be accompanied by improved action aimed at tackling the systemic culture of corruption that impedes service delivery.

- Immediate interventions to mitigate against corruption and crime – At a local level, these must focus on both administrative and political officeholders. A culture of transparency must be ingrained into local governance via building effective monitoring, regulation, and oversight mechanisms into processes.

- Furthermore, as above, prioritising responsiveness by officials in administrative and political office bearers through consultatory processes of governance will be beneficial.