(John McCann/M&G)

It’s been in existence since the 1500s but the Kaaps language, synonymous with Cape Town in South Africa, has never had a dictionary until now. The Trilingual Dictionary of Kaaps has been launched by a collective of academic and community stakeholders – the Centre for Multilingualism and Diversities Research at the University of the Western Cape along with the hip hop-driven community NGO Heal the Hood Project. The dictionary – in Kaaps, English and Afrikaans – holds the promise of being a powerful democratic resource. Adam Haupt, director of the Centre for Film & Media Studies at the University of Cape Town, is involved in the project and tells us more.

What is Kaaps and who uses the language?

Kaaps or Afrikaaps is a language created in settler colonial South Africa, developed by the 1500s. It took shape as a language during encounters between indigenous African (Khoi and San), South-East Asian, Dutch, Portuguese and English people. It could be argued that Kaaps predates the emergence of an early form of Kaaps-Hollands (the South African variety of Dutch that would help shape Afrikaans). Traders and sailors would have passed through this region well before formal colonisation commenced. Also consider migration and movement on the African continent itself. Every intercultural engagement would have created an opportunity for linguistic exchange and the negotiation of new meaning.

Today, Kaaps is most commonly used by largely working class speakers on the Cape Flats, an area in Cape Town where many disenfranchised people were forcibly moved by the apartheid government. It’s used across all online and offline contexts of socialisation, learning, commerce, politics and religion. And, because of language contact and the temporary and seasonal migration of speakers from the Western Cape, it is written and spoken across South Africa and beyond its borders.

It is important to acknowledge the agency of people from the global South in developing Kaaps – for example, the language was first taught in madrassahs (Islamic schools) and was written in Arabic script. This acknowledgement is imperative especially because Afrikaner nationalists appropriated Kaaps in later years.

For a great discussion of Kaaps and explanation of examples of words and phrases from this language, listen to this conversation between academic Quentin Williams and journalist Lester Kiewit.

How did the dictionary come about?

The dictionary project, which is still in its launch phase, is the result of ongoing collaborative work between a few key people. You might say it’s one outcome of our interest in hip hop art, activism and education. We are drawn to hip hop’s desire to validate black modes of speech. In a sense, this is what a dictionary will do for Kaaps.

Quentin Williams, a sociolinguist, leads the project. Emile Jansen, Tanswell Jansen and Shaquile Southgate serve on the editorial board on behalf of Heal the Hood Project, which is an NGO that employs hip hop education in youth development initiatives. Emile also worked with hip hop and theatre practitioners on a production called Afrikaaps, which affirmed Kaaps and narrated some of its history. Anthropologist H. Samy Alim is the founding director of the Center for Race, Ethnicity and Language at Stanford University and has assisted in funding the dictionary, with the Western Cape’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport.

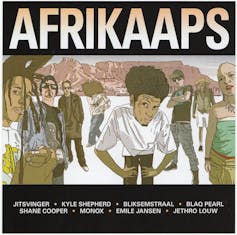

CD art from the musical Afrikaaps.

CD art from the musical Afrikaaps.

Courtesy of Afrikaaps/Dylan Valley

We’re in the process of training the core editorial board in the scientific area of lexicography, translation and transcription. This includes the archiving of the initial, structured corpus for the dictionary. We will write down definitions and determine meanings of old and new Kaaps words. This process will be subjected to a rigorous review and editing and stylistic process of the Kaaps words we will enter in the dictionary. The entries will include their history of origin, use and uptake. There will also be a translation from standard Afrikaans and English.

Who will use the dictionary?

It will be a resource for its speakers and valuable to educators, students and researchers. It will impact the ways in which institutions, as loci of power, engage speakers of Kaaps. It would also be useful to journalists, publishers and editors keen to learn more about how to engage Kaaps speakers.

A Kaaps dictionary will validate it as a language in its own right. And it will validate the identities of the people who speak it. It will also assist in making visible the diverse cultural, linguistic, geographical and historical tributaries that contributed to the evolution of this language.

Kaaps was relegated to a slang status of Afrikaans?

Acknowledgement of Kaaps is imperative especially because Afrikaner nationalists appropriated Kaaps in order to create the dominant version of the language in the form of Afrikaans. A ‘suiwer’ or ‘pure’ version, claiming a strong Dutch influence, Afrikaans was formally recognised as an official language of South Africa in 1925. This was part of the efforts to construct white Afrikaner identity, which shaped apartheid based on a belief in white supremacy.

For example, think about the Kaaps tradition of koesiesters – fried dough confectionery – which was appropriated (taken without acknowledgement) and the treats were named koeksisters by white Afrikaners. They were claimed as a white Afrikaner tradition. The appropriation of Kaaps reveals a great deal about the extent to which race is socially and politically constructed. As I have said elsewhere, cultural appropriation is both an expression of unequal relations of power and is enabled by them.

When people think about Kaaps, they often think about it as ‘mixed’ or ‘impure’ (‘onsuiwer’). This relates to the ways in which they think about ‘racial’ identity. They often think about coloured identity as ‘mixed’, which implies that black and white identities are ‘pure’ and bounded; that they only become ‘mixed’ in ‘inter-racial’ sexual encounters. This mode of thinking is biologically essentialist.

Of course, geneticists now know that there is not sufficient genetic variation between the ‘races’ to justify biologically essentialist understandings. Enter cultural racism to reinforce the concept of ‘race’. It polices culture and insists on standard language varieties by denigrating often black modes of speech as ‘slang’ or marginal dialects.

Can a dictionary help overturn stereotypes?

Visibility and the politics of representation are key challenges for speakers of Kaaps – be it in the media, which has done a great job of lampooning and stereotyping speakers of Kaaps – or in these speakers’ engagement with governmental and educational institutions. If Kaaps is not recognised as a bona fide language, you will continue to see classroom scenarios where schoolkids are told explicitly that the way in which they speak is not ‘respectable’ and will not guarantee them success in their pursuit of careers.

This dictionary project, much like ones for other South African languages like isiXhosa, isiZulu or Sesotho, can be a great democratic resource for developing understanding in a country that continues to be racially divided and unequal.

Adam Haupt, , University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.