Scene of daily life in a Bantustan, or Homeland, near Johannesburg in South Africa, in February 1963. The bantustans or homelands were African reserves allocated to the country's different black ethnic groups, established in 1951 by the "Bantu Authorities Act" introduced by the government of Daniel Francois Malan as part of the policy of apartheid. These homelands were independent states to which each African was assigned by the government according to the record of origin, losing his citizenship in South Africa and any right of involvement with the South African Parliament which held complete hegemony over the homelands. (Photo by EPU/AFP)

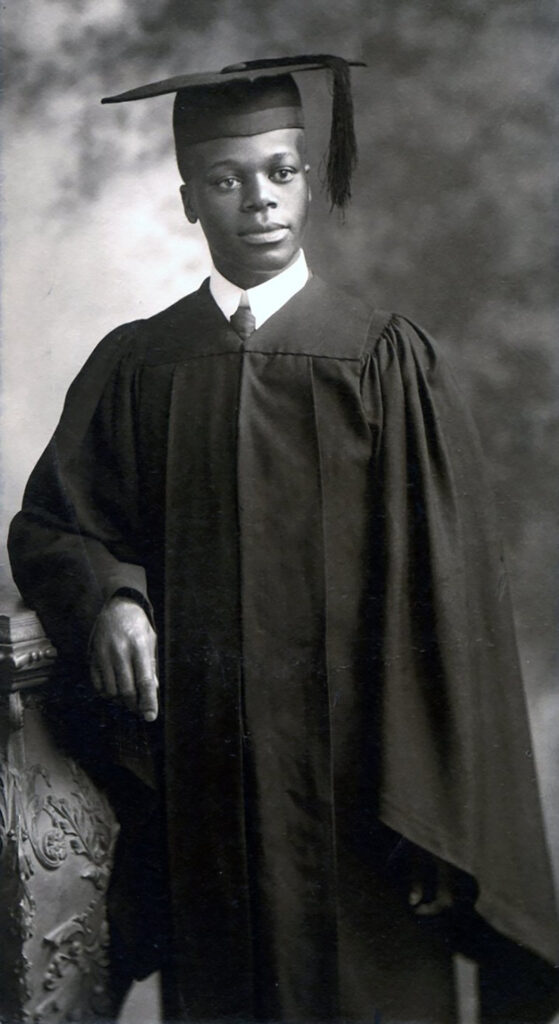

On 2 October 1910, a steamer from England arrived on South African shores. Among those on board was Pixley ka Isaka Seme.

Since leaving for America 13 years earlier, Seme had become an accomplished gentleman. Fluent in English, he also spoke Dutch and French; he could play the piano, and enjoyed a game of snooker or tennis. He also held a BA degree from a prestigious Ivy League university. And while he had not completed his Bachelor of Civil Law at Oxford, he had qualified as a barrister in London.

Seme was a cosmopolitan man of the world, having lived in New York, Oxford and London, and visited Paris and Holland.

With Seme’s return to South Africa, there was a sense of great expectation. The land he had left behind was not the same as that he returned to. In 1910 the whites-only Union of South Africa had been established as a country under British dominion. Natal and the Cape were no longer colonies, but provinces of South Africa, as were the two former Boer Republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State.

A new, though shifting, “South African identity” had been thrust on his people.

Black people were by now, in law no longer citizens but subjects of the new white racial oligarchy. Seme’s urgent vision was the rejection of tribalism, ethnicity and provincialism in favour of a black nationalist identity. He wanted to work towards a South African Native Convention to form a national political organisation.

Today, we know this organisation as the African National Congress.

The idea of the formation of a national black organisation has a strong historical pedigree which predates Seme’s arrival to the scene by far. Yet Seme’s role in the formation of the modern version of the ANC remains central.

The ANC’s founding constitution adopted in 1912 would be revised six years later by a young lawyer, Richard Msimang. His greatest contribution was to focus the party to its mission of the age: land.

Mabawuyek’umhlaba wethu (leave our land alone)

The backstory to the formation of the ANC was land.

To understand this, we should examine some events that took place in the period immediately before January 1912. The Union of South Africa came into being on 31 May 1910. Then, there were some six million Africans, four million of which lived in “South Africa” and another two million in the reserves — forerunners to the “homelands” in a total population just in excess of eight million people. The reserves were the result of the territorial conquest of the 19th century.

Although during apartheid there was a tendency to deny African ownership of the land, it was the first prime minister, Louis Botha, who admitted in 1916 that “the natives” were here when the Europeans arrived. By the end of the 19th century, most African land was under the control of Europeans.

Historian Leonard Thompson, author of A History of South Africa, estimates that the Zulu lost two-thirds of their land, while the Tswana lost more than that, because of Afrikaner and British conquest. The Xhosa in the Cape and the Sotho in the Free State lost more than 90% of their land.

Remarkable: Pixley ka Isaka Seme helped establish what became the ANC to present African views to the state, but this was not realised

Remarkable: Pixley ka Isaka Seme helped establish what became the ANC to present African views to the state, but this was not realisedArising from this, new relationships to the land were forged. Most Africans simply lived on land owned by Europeans with no legal rights to it, often referred to as “squatters”.

Land had been commodified. It could be bought and sold in the market, although the market itself was created through the racial lens and reflected state policy, rather than unpredictable economic forces. Ownership of land was proved through the mechanism of title deed.

There was an uneven dispensation here. In the Cape, Africans could purchase land according to the individual tenure system, although there were vast restrictions on this arising from the Glen Grey Act, 1894, which stipulated that African purchases of land had to be approved by the colonial government. The result was that in practice few Africans owned land in their own right. Mostly, land was held in communal tenure systems.

In the Free State there was an outright prohibition to the purchase of land by Africans. In the Transvaal, official policy was to prohibit African land acquisition although no formal law existed to that effect.

After the 1905 case of Edward Tsewu v Registrar of Deeds, which confirmed that Africans had the right to acquire land, official policy changed. Now, Africans could buy land in their own name, but the common practice remained that land was bought through white intermediaries such as native commissioners and Christian missionaries.

These land acquisitions were largely marginal and did not affect the actual land territory held by Africans, which remained largely representative of the land taken through conquest.

Yet after the formation of the Union, white farmers, under the political influence of Barry Hertzog, then minister for native affairs in the Botha administration, began to agitate for a uniform land policy, to guarantee the security of white control over the land.

Hertzog, in some respects, can be viewed as the intellectual father to Hendrik Verwoerd, widely regarded as the “architect of apartheid”. He opposed “mingling of the races”, and proposed that each race must “develop along their own lines”. On land, he was unequivocal that Africans should not own land in the “white man’s territory” and no white person should acquire land in “native reserves”.

The problem was that there was no legal entity known as a “white man’s territory”.

The Natives Land Act: racism in land

By December 1911 — as Seme was busy with preparations for the launch of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) — the Union government proposed the Native Settlement and Squatters Registration Bill. It roughly concerned measures to restrict African land purchases and ownership and to regulate the rights of “squatters” on white-owned land. Although the Bill did not become law, its essence was taken up with much energy by Hertzog in the coming months.

He conceived the idea of a native land legislation that would divide the country into two — one section for Europeans and the other for the rest. What he wanted to achieve was territorial segregation. But, as he drafted the legislation, he appreciated that this was not possible, so the draft legislation focused on legal rights, rather than physical occupation.

White people could own land in European areas. Africans could not own land, even in native reserves, without forms of trusteeship under the tutelage of the white administration. “Squatting” was made illegal and criminal sanctions were proposed. The native reserves were placed under the control of the state. That way, segregation in politics could be translated to racism in land.

When the Natives Land Bill made its way to parliament, in May 1913, Hertzog had been fired from the cabinet. He had been replaced by the liberal minded JW Sauer, a one-time ally of John Tengo Jabavu, the founder and editor of Imvo Zabantsundu.

But Sauer could not prevent the passing of the Native Land Act, with its obnoxious content as theorised by Hertzog. Black people’s views were not solicited and the Bill was publicised for only five weeks before it was passed as law, between 5 May and 19 June 1913. Its central tenet was the creation of “scheduled areas”, which demarcated areas for Native and European occupation.

From the 1916 report of the Natives Lands Commission, these areas are reflected as follows: For the Cape, 8.45%; Natal, 22.83%; Transvaal, 3.33% and Free State, 0.48%, which gave a national total of less than 8% of all land available in the country.

Section 1 of the Act proclaimed that no native could buy land in European areas and no European could buy land in native reserves, without the permission of the government.

There is evidence the right to grant permission to acquire land in European areas was sometimes granted by the government, but it did not affect the larger picture of the land occupation. The situation somewhat improved in 1936, when new areas were added into the schedule to increase the land size available in native reserves to around 13%.

Deprivation of land, wealth and livelihood

While Seme might have thought that the SANNC should be a vehicle for the conveyance of native views to the government, this wish was dashed by the realisation that any liberal pretensions of Louis Botha would yield to the radical views of Hertzog. White people were consolidating their control over territory and black voices were subjugated.

Solomon Plaatje writes in his Native Life in South Africa, first published in 1916, that in May 1913 a congress deputation led by Mpilo Walter Rubusana, which included Alfred Mangena and Plaatje, met government representatives to oppose the proposed “embargo on the purchase and lease of land’’ by Africans.

This failed, as Plaatje notes, because of the desire on the part of the government to “retain the support of the Free State malcontents”.

There were too many instances of stories of hardship brought by the Act. The SANNC decided on a uniform policy to the Act, asking the young lawyer Msimang to record African experiences of the Act. The effect of the Act was wider than land deprivation.

In Thaba Nchu, people who had been evicted were told by the government “to sell all their stock, and return to the farms to labour in capital as unpaid servants”. Or “to go to the reserves”. The government itself was responsible for evicting Africans from its own lands — Crown land: “79 and 100 individuals or more families at Peters and Colwoorth respectively are being ejected by the government itself in anticipation of the supposed requirements of this law”.

The ejections from farm land were being deliberately made “with the sole intention of debt-enforced labour, as provided in the Act. White farmers know fully well that since the Act, natives are no longer free to obtain land or to make terms for occupation of land.”

In Natal there were 436 000 “squatters” and in the Free State about 80 000. Most in Natal had been given six months’ notice to vacate while in the Free State the average duration of a notice to vacate was five days and some had been given “one hour’s notice to leave and trek”. These caused “loss of buildings without compensation, and reduction to a state of vagabondage with no prospect of permanent settlement”.

Bid: Public hearings on land expropriation were held in 2018 but an amendment to the Constitution failed in 2021. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Bid: Public hearings on land expropriation were held in 2018 but an amendment to the Constitution failed in 2021. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

The black people that Msimang interviewed had given him the number of livestock that they possessed. Thus, he concluded that the effect of the Act was not merely going to be removal from land, but deprivation of African wealth and livelihood.

With the accounts, the ANC was able to note that what the Native Land Act achieved were three interrelated outcomes. Loss of land: the security of tenure enjoyed by black people was drastically curtailed and they could be evicted at the whim of the government and any white person.

Loss of property: particularly in the form of cattle. The cattle were not “lost”; they were confiscated and taken away by white farmers. Often, sham transactions were entered into, in terms of which blacks were compelled to “sell” their cattle to have a place to stay.

The third was a conversion overnight of black people into a class of labourers.

There was loss of citizenship too, as many Africans left South Africa to settle in Lesotho and Botswana.

These findings, and Plaatje’s work on land, served as a basis for the ANC approach on the Native Land Act. What they wanted was the “right of the native to the free purchase of and dealing with land on the same terms as the white subjects of Your Majesty”.

110 years later

I have written about the founding generation of the ANC and their struggles for land.

Land remains central to the imagination of citizenship of today’s ANC. Yet the evidence since 1994 shows hesitation, timidity and indifference to the resolution of land. The disaster with the abortive constitutional amendment has been illustrative of a larger malaise.

While the ANC negotiated a radically transformative Constitution in 1996, it seems to have been reluctant to enforce it. Let me focus only on expropriation to make my point.

Section 25(2) of the Constitution explicitly states that property (including land) “may be expropriated only in terms of law of general application” (a) for a public purpose or in the public interest; and (b) subject to compensation, the amount of which and the time and manner of payment of which have either been agreed to by those affected or decided or approved by a court.”

Quite clearly, land can be expropriated by the state.

There is nothing “implicit” here to justify explication by an amendment to the text. When it expropriates, the state must act in terms of a law of general application. The ANC holds a majority of seats in parliament. It is entitled to pass a law, provided it complies with the Constitution, to grant itself the power to expropriate land to meet the land crisis. Yet in our statute books we remain stuck with the 1975 Expropriation Act. There is no reason this is so.

Let us now consider the second facet of section 25(2), that of compensation.

The ANC has falsely touted the notion that the payment of compensation — at whatever level — accounts for the “slow pace” of land reform. But there is plainly no evidence that this is so.

Every credible research undertaken in this regard shows that compensation is a marginal factor in the failure of land reform. There are other, much more formidable obstacles, including state capacity, corruption, institutional design and policy confusion.

Yet the ANC has simply failed to place these items on the agenda for discussion.

There is a further problem with the compensation dynamic. Since 1997 the ANC adopted a policy of “willing seller, willing buyer” through which it has been over-compensating white landowners, in breach of the constitutional requirement that compensation must reflect an equitable balance between the interests of those affected and the public interest and in any event must be “just and equitable”.

The ANC has never sought to flesh out in policy or legislation the content of just and equitable compensation, resorting to vague and abstract suggestions.

For the past four years, the ANC has been obsessed with the notion of depriving landowners’ financial compensation. Until December 2017, the idea did not appear from any of the historical records of the ANC. Its recent adoption by the ANC has been influenced by the Economic Freedom Fighters. But it is unclear how the ANC proposes to flesh this out, after the predictable failure of the proposed constitutional amendments.

One approach is to make amendments to the present draft of the Expropriation Bill, to render it applicable to wider land reform expropriations. At the moment, section 2 of the draft Bill limits its application to property acquired for state use. So, for instance, a farm expropriated for redistribution will fall outside the purview of the new Expropriation Act.

Farmland is regulated by the restitution legislation, passed in 1994. But that legislation restricts expropriations to instances where there is no dispute about the validity of the claim. The effect of this is even after the Expropriation Bill is passed into law, the state will not have the wider expropriation powers to effect land reform, under the Constitution. The valuer-general has no powers of expropriation. Its role is to determine the value of the land, using the modality in its own legislation.

Another approach is to leave granular intellectual work to the courts. If this is the approach to be adopted, it is necessary for the state to play an active role in the judicial system, pushing through the cases it has selected to test the limits of the Constitution.

The state needs to be a true ally of the landless, ensuring that it respects their rights to restitution and that it is committed to constitutional governance. Our Constitution is a product of war. It was adopted so that our basic rights are sourced in law. Land restitution is not a favour to be dispensed by the government, at will. It is a right enforceable by law.

In its 110th year of existence, it is necessary for the ANC to recall the vision of its founders. They lacked formal political power. They had idealism. Often, today’s political class, which is indifferent to suffering, has no idealism.

There is a risk that the indifference will soon turn to a great betrayal. ANC founders believed in constitutional governance. But they believed in justice too. By returning to constitutionalism, we can pay homage to the founding generation.

Tembeka Ngcukaitobi SC is a South African advocate, acting judge, public speaker, author and political activist. He is a member of the South African Law Reform Commission