After 60 years of air pollution by oil refineries, it will take Wentworth residents at least two generations to reverse epigenetic changes. Photo: Supplied

Not much has changed in the 40 years since Shareeza Domingo’s family moved out of Wentworth.

It is a Saturday morning and the streets are beginning to buzz with children’s voices as they prepare to partake in soccer fixtures scheduled around the neighbourhood. Even those who don’t play for official school teams at the sporting grounds opposite Engen‘s rotting refinery are putting together teams for tournaments at makeshift pitches next to its infamous flats. Aunty Kat is already seated at her spot in the shade of an adjacent tree, where she spends her days waving at passersby.

Wentworth is certainly one of those South African townships where everyone knows everyone else.

Former resident Domingo recalls a typical weekend in the neighbourhood during her youth: “There was little to be done in the 1970s, I would say. Basically, it would be a trip to town to do your shopping, get back and the kids were all in the road and everyone was playing, parents are braaing and having time together.”

Domingo’s fond memories of her childhood neighbourhood prompted her to show her daughters, Lamise and Mahira, where both of their parents were born and raised. Having lived in the northern part of Durban since 1992, she felt it important to give them a sense of where their family was rooted, a community she always speaks of with tremendous pride.

It was exactly how she remembered it to be: the way it looked, sounded and felt. The community still finds joy even in its hardship. But just a few moments into their excursion, Domingo quickly remembers the real reason they had packed up their four-bedroom home in exchange for a small apartment in Durban’s central business district: “the smell” that killed her father.

“When we entered Wentworth my two girls said to me: ‘Wow, y’all had to live in that smell? That smell that’s stinking? I can’t breathe.’ My eldest one’s father is also from Wentworth, and he also had asthma. She also has asthma and kept saying, ‘I’m choking, I’m choking.’ So, we just left.”

Former Wentworth resident Shareeza Domingo in the Durban apartment her family moved to in 1992, after her father grew gravely ill from the pollutants he was exposed to while working at a large refinery in the South Durban Basin.

Former Wentworth resident Shareeza Domingo in the Durban apartment her family moved to in 1992, after her father grew gravely ill from the pollutants he was exposed to while working at a large refinery in the South Durban Basin.

Poverty in the air

Wentworth, situated in the South Durban Basin, is surrounded by nearly 300 petrochemical industrial sites, with more than 150 smokestacks. Formalised under the Group Areas Act during the apartheid regime, its population is still predominantly coloured.

Much like other so-called coloured communities across South Africa, this community continues to spiral into economic despair despite the country’s hard-earned democracy. But, unlike other townships in the north of Durban with similar racial compositions, one of the key drivers of poverty experienced here is the elevated rate of illness due to long-term exposure to air pollution created by the surrounding industries.

“Although children both in the north and the south were affected by the pollution, the children in the south had much more asthma than the children in the north,” says Professor Rajen Naidoo, an epidemiologist and head of occupational and environmental health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

The University of KwaZulu-Natal’s groundbreaking research into the impact of air pollution on the South Durban community began 20 years ago when residents reported alarming numbers of pupils losing consciousness at school.

“Work really started with a single school, the Settlers’ Primary School. There was an incident where a large number of children were collapsing and it was attributed to the elevated levels of pollution in the area,” explains Naidoo.

“Settlers’ Primary was a very interesting school. If you stand out in the playing fields of that school, if you look out in one direction, you see some stacks of the Engen refinery. If you turn around, directly behind you, you see the smokestacks of the Sapref refinery [Shell and BP]. So clearly depending on which direction the wind blew on a particular day, that school was always in the middle of it.”

It was then that they discovered that the area was indeed a cancer cluster, with leukaemia rates in children under the age of 10 at least 24 times higher than the national average — but continued study of the community revealed a more dire situation.

“We hypothesised that it is possible that there is something that genetically reshapes children such that they become more susceptible to develop asthma, because historically we know that asthma is a genetics-based disease,” adds Naidoo.

“It seems likely that the pollutants are causing what we refer to as an epigenetic change over a shorter period of time within generations … and that it is still likely that the next generation or two will still be carrying some of the pollutant-related burden going into the future.”

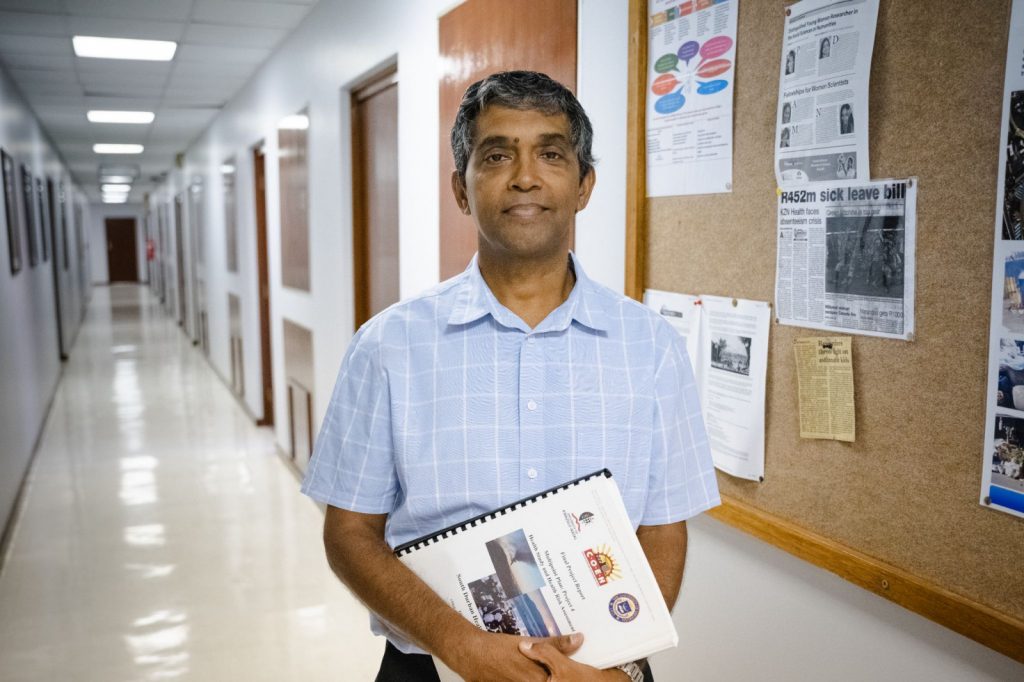

Epidemiologist and head of occupational and environmental health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal Professor Rajen Naidoo holding the results of their groundbreaking study into the genetic changes experienced by the South Durban community due to air pollutants from the surrounding oil refineries

Epidemiologist and head of occupational and environmental health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal Professor Rajen Naidoo holding the results of their groundbreaking study into the genetic changes experienced by the South Durban community due to air pollutants from the surrounding oil refineries

Air pollution’s long-lasting legacy

It is then not surprising that despite their move out of Wentworth even before her daughter’s birth, Domingo’s eldest daughter suffers from asthma today — just like her father.

“People thought, ‘It’s in the genes.’ They’d say: ‘So, the father had asthma, it follows the same genes. Of course, the child will follow.’ That’s what people would say. They knew that the oil refinery was a hazard, but how do you prove that?”

While the Domingo family were able to move out of Wentworth, for most of the residents of the South Durban Basin there is no refuge from the highly polluted neighbourhood. Naidoo explained that when the lion’s share of an already marginal income is rationed toward the healthcare needs of chronically ill children, there is nearly nothing left to help families escape this toxic environment.

“A lot of the people have been staying there for three or four generations because they are not able to step out. Parents build their children so that they can move up into the next level and escape that poverty cycle, but they are not able to do that in South Durban.”

“Our young people are suffering worse off than ever before. Not only is there a double dose of asthma, cancer and leukaemia, but they don’t have money to study further,” said veteran environmental justice activist and co-ordinator of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance Desmond D’Sa.

D’sa’s mission to protect his community’s constitutional right to a healthy environment earned him the 2014 Goldman Prize. His family was split up by the Group Areas Act when he was a child — with only some of his siblings moved to Wentworth, while others were placed in other racially-based neighbourhoods.

He co-founded the environmental movement in Durban in response to the large number of injuries and deaths experienced by workers at the refineries due to the toxicity of their work environment. D’sa says that not only are these oil giants evading responsibility for the suffering they have and continue to cause, but they are also further disenfranchising the community through their discriminatory employment practices.

“Engen doesn’t have a habit of employing budding engineers from the community. In fact, they don’t employ our skilled people here because they know through the medical assessments that they do that already people are affected with their health. So why would they employ people from here?”

Gender-based violence activist Oliver Meth stands outside his childhood home, holding an acknowledgement of his contribution to South Africa’s constitutional values, awarded to him by President Cyrll Ramaphosa. The Engen refinery can be seen in the background

Gender-based violence activist Oliver Meth stands outside his childhood home, holding an acknowledgement of his contribution to South Africa’s constitutional values, awarded to him by President Cyrll Ramaphosa. The Engen refinery can be seen in the background

Toxic relations

Soaring unemployment rates in the community, coupled with the mounting financial burdens created by chronic health issues, has had a toxic knock-on effect on the social fabric of Wentworth.

“A sense of hopelessness comes in when a person is unemployed, and those frustrations obviously get carried out and are seen visibly within the community through the abuse of substance, physical violence and the manipulation within your own personal relations,” says Oliver Meth, a gender-based violence activist from Wentworth.

In 2002, Meth was brutally raped by a group of young men in his community. He was just 16. When he approached the police to report the crime, he was ridiculed and turned away. This hate crime was later used as a case study when the South African government was forced to expand its Sexual Offences Act to include all forms of nonconsensual sexual penetration regardless of gender as rape.

His story is but one example of the lack of institutional support in the community, as well as the extremely high levels of gender-based violence in Wentworth. Meth believed that the only way this community can rid itself of the worst social symptoms of systemic inequality that plague it is to create more economic opportunities for its residents.

“The main struggle for them is that people are thinking about the immediate, like to put food on the table, and not the long-term consequences that these refineries pose to them. The long-term effect is not as important to them for now because they are just trying to get through the day,” adds Meth.

Currently, there are very few opportunities available outside of these toxic industries, and what little opportunity remains continues to be threatened by the fossil fuel industry. While these oil giants have all announced their plans to finally abandon these rotting refineries, several more are scrambling for drilling rights along the Southern African coastline.

Veteran environmental justice activist and co-ordinator of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance Desmond D’Sa stands on the veranda of the organisation’s offices. His home can be seen behind him and smokestacks of another refinery behind that.

Veteran environmental justice activist and co-ordinator of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance Desmond D’Sa stands on the veranda of the organisation’s offices. His home can be seen behind him and smokestacks of another refinery behind that.

Clearing the air

With firsthand knowledge of the exploits of big oil, local fishers and indigenous peoples groups fight tirelessly in court to prevent any further loss to their livelihoods because of greedy, colonial industries. Corporations continue to take advantage of countries whose environmental laws are less strict than in the countries these multinationals are headquartered in, according to Naidoo.

“We’ve got to, firstly, have a situation where polluters accept responsibility for what they are doing and what they have done in the past. We’ve got to have a government which holds those polluters responsible, make sure they understand what they’ve done and put into place plans that redress that,” says Naidoo.

“And yes, it can be done. If these companies have been generating massive amounts of profits for all these years, then now, it’s in a sense, payback time. You’ve exploited these communities. You’ve exploited these environments. Now, you’ve got to make good.”

“We don’t want these big corporations running away from the country. We want them to be held accountable for people’s health, and also to be held accountable for the workers,” adds D’sa.

“The oil refineries robbed a lot of them of their livelihoods, their families and their loved ones. To find a way to resolve that is rather late but go back and see what you’ve done to the people and rectify it. Compensate them, but money doesn’t save it, at the end of the day,” concludes Domingo.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.