Picture this: A portrait of Russia’s President Vladimir Putin in a restaurant in Kyiv, Ukraine. The International Criminal Court has charged him over the abduction and deportation of children during the war in Ukraine.

South Africa’s ruling party, the ANC, held a national executive committee meeting from 21 to 24 April. One of the resolutions coming out of the meeting was that the ANC had decided to withdraw South Africa’s membership from the International Criminal Court (ICC).

This was neither the first time that the party had made this decision nor was the main reason for it novel. While there is justification for grievances against the ICC, the ANC’s stance, timing and about-face reek of confusion and its reason is uninspiring.

This should not be an absolution of the ICC, as its selective indictments and deference to the UN Security Council are shocking absurdities. The ANC’s exasperation with the ICC is understandable, but knee-jerk, and its public changes of mind do not inspire hope for the creation of African instruments of juridical recourse.

Focusing attention on the ICC and its raison d’être is appropriate here.

The ICC was established on 17 July 1998. The Rome Statute, which came into force in July 2002, on which the ICC is based, was a major transfer of prosecutorial authority from sovereign states to an international institution. The ICC was tasked with dealing with atrocity crimes.

Designed to prevent and end impunity and offer justice to victims, the court’s jurisdiction charged it with “prosecuting individuals, including senior political and military leaders”.

In a world that had seen ethnic decimation in the former Yugoslavia, and the 1994 Rwandan genocide, an international remedy was justified, especially if victims of crimes lived in countries where prosecutorial institutions were fledgling or non-existent.

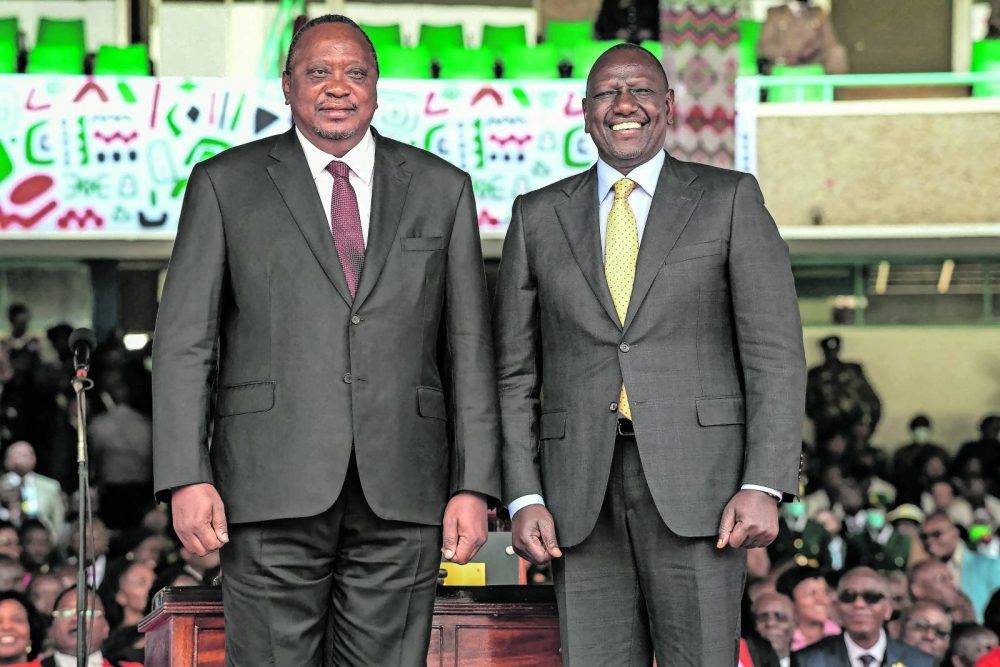

Awkward: Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy at the time William Ruto were charged by the International Criminal Court while still in office. Photo: Simon Maina/Getty ImagesFruto

Awkward: Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy at the time William Ruto were charged by the International Criminal Court while still in office. Photo: Simon Maina/Getty ImagesFruto

The ICC has intervened in about 28 situations and issued warrants of arrests to just over 50 individuals. Thus far, its record of completed prosecutions is a pathetic five, curtailed as it is by its treaty-based jurisdiction.

Apart from this limitation, the ICC is also assailed by persistent accusations of almost exclusively focusing on African perpetrators.

Furthermore, the Security Council can refer a situation to the ICC, which empowers the ICC to investigate all four crimes which fall under the Rome Statute, including crimes of aggression, without further conditions.

“The Security Council’s powers under the UN Charter are the legal basis upon which the ICC can investigate such crimes without any consent requirement by the states involved.”

Therein lies one of the main grievances on which the ANC’s stance is based. Russia, the US and China, permanent members of the Security Council, are not part of the 123 states that are party to the Rome Statute.

This creates problems for indicted parties, as they could ultimately come under pressure from the Security Council, even if some of its members are immune from prosecution. It would seem, then, unless the ICC’s jurisdiction is broadened to include, say, all members of the UN, it will be criticised for selective justice.

At face value, the African Union (AU) should endorse the ICC’s stance against impunity because the transformation of the Organisation of African Unity into the AU in 2002 saw the insertion of the principle of non-indifference — in other words, giving the AU powers to intervene in members states where atrocities were committed.

However, and for good reason, African actors have impugned the credibility of the ICC, accusing it of exercising a selective brand of justice.

America and Britain’s 2003 blunder in Iraq is often cited as a glaring case that should have got the court’s attention. Apparently, it would have been reassuring for Africans to see former US president George Bush, his mandarins in the State Department and at the UN, and ex-British leader Tony Blair arraigned before the ICC for starting a war when there is evidence the casus belli was a travesty.

Furore: South Africa failed to arrest then Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir when he visited the country in 2017 as the Rome Statute said it should. Photo: Ashraf Shazly/Getty Images

Furore: South Africa failed to arrest then Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir when he visited the country in 2017 as the Rome Statute said it should. Photo: Ashraf Shazly/Getty Images

Nothing was done, and eight years later when Libya was laid waste to in the pursuit of liquidating Muammar Gaddafi, the West, once again, seemed to have got away with murder — literally.

However, when it comes to African suspects, the ICC has been remarkably proactive — much to the predictable chagrin of Africa. What is worse, incumbent politicians such as Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir and later Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto were slapped with ICC charges and were expected to be arraigned while they were in office.

For South Africa, this was a step too far. In 2015, Al-Bashir travelled to South Africa for an AU summit. He was not arrested. The government was taken to court for its apparent dereliction and two courts ruled against it.

In response, the South African government railed against the ICC and threatened to abandon the court. In 2017, the ICC confirmed the rulings stating that South Africa’s refusal to arrest Al-Bashir was “contrary” to the country’s obligation as a signatory to the Rome Statute.

However, the ICC did not refer South Africa to the Security Council or to the Assembly of States Parties for censure. With the passage of time, South Africa quietly dropped its intention to leave the ICC. Until now.

On 17 March, the ICC issued a press release that read: “Today … Pre-Trial Chamber II of the International Criminal Court (“ICC” or “the Court”) issued warrants of arrest for two individuals in the context of the situation in Ukraine: Mr Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin and Ms Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova.”

Russian president Putin is allegedly responsible for the war crime of unlawful deportation of children and that of their unlawful transfer from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation. The crimes were allegedly committed in Ukrainian occupied territory at least from 24 February last year, when the hostilities commenced.

South Africa finds itself in a quandary once again as Putin is scheduled to travel to the country for a Brics summit in August. Immediately after the warrant was issued, there was speculation about whether South Africa would extend an invitation to Putin. After initial dithering, the invitation was duly issued, paving way for last month’s ANC resolution to abandon the Rome Statute, once again.

On 24 April, President Cyril Ramaphosa hosted Finland’s President Sauli Niinistö, in whose presence he said the ANC had decided to leave the ICC because of “unfair treatment”. All hell broke loose, as the party was criticised by detractors, mainly from the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the media.

Later on the same day, presidential spokesperson Vincent Magwenya compounded the furore by contradicting Ramaphosa, stating South Africa would remain a member of the ICC and would use its membership to campaign for consistent application of international law.

It cannot be gainsaid that Magwenya’s about-turn came at the direction of his boss, thereby proving Ramaphosa parroted an ANC stance to Niinistö that he personally, and as head of government, did not endorse.

Alan Winde, the DA premier of the Western Cape, lampooned the government for its vacillations. Knowing very well Putin probably wouldn’t go to the Western Cape, Winde threatened to arrest him if he did.

The ANC did not help its cause by sending mixed messages due mostly to the conflation and confusion of party mandates and government obligations. Author Qaanitah Hunter wrote a scathing critique in News24 describing the ANC’s and the government’s confounding statements as symptomatic of Ramaphosa’s “spineless leadership”.

On 27 April, Minister in the Presidency Khumbudzo Ntshavheni reported on a cabinet meeting convened by Ramaphosa. She confirmed “South Africa’s participation in the International Criminal Court and confirms that we remain a signatory to the Rome Statute” and that the president had configured an inter-ministerial committee, led by Deputy President Paul Mashatile.

The committee would consider “various options on the matter of the ICC as it relates to the visit of some of our guests during the Brics Summit.”

The International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda (centre left), holds a press conference during her visit to Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 2018 to look into allegations of extreme violence. Photos: Roman Pilipey/Getty Images & John Wessels/Getty Images

The International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda (centre left), holds a press conference during her visit to Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 2018 to look into allegations of extreme violence. Photos: Roman Pilipey/Getty Images & John Wessels/Getty Images

What, then, does the volte-face mean for Putin’s visit? It seems almost certain South Africa has no appetite to arrest him, which complicates the different messages coming from the ruling party and the government.

This also goes to the heart of whether (South) Africa should leave the ICC to eliminate the awkwardness that comes with indictments of incumbent leaders.

When one cuts through South Africa’s diplomatic chaff and assurances of solidarity with non-Western players — the usual candidates for ICC prosecution — the country comes across as a devoted supporter of international instruments such as the ICC.

The ANC keenly remembers how crucial international instruments and players were in shining a spotlight on the evils of apartheid. However, it is also ideologically tethered to wistful memories of how the developing world, and Russia, shored up the anti-apartheid struggle.

How, then, does the ANC contribute to preventing impunity, while at the same time supporting its former comrades-in-arms when their leaders are summoned to the ICC?

As it stands, the ICC, with its flaws, offers some assurance to victims of atrocities. It sounds patriotic to opt for an African recourse for suspected atrocity crimes, but what would happen in the time that such an instrument was under construction?

There are justifiable grounds for opting for alternatives to the ICC but the ANC’s flip-flopping antics are certainly not a reliable formula.

An honest question is also whether an insular organ would be in kilter with a multilateral global order. Would one expect, for example, that a Russian court would be objective in trying that country’s sitting president, especially one as near omnipotent as Putin? In Africa’s case, is it wiser to abandon an existing instrument in a forlorn hope of an African alternative or to remain in the court while campaigning to change it from inside?

In addition, to inveigh against the ICC’s alleged selective application of justice is all well and good, until one is challenged on whether there are grounds for questioning the many Africans, and now Russians, who have been summoned to the ICC. These are difficult questions to which South Africa and the African continent should respond.

Another grievance, that came out during the cases of Kenyatta and Ruto, is incumbent leaders should not be made to stand trial at the ICC. This would be laughable if the dangers were not fatal and irreversible.

It is disingenuous to say incumbents should not be tried because this is likely to perpetuate the scourge of lifelong leaderships. The continent is already littered with leaders who, for fear of reprisals and accountability, are not shy to change constitutions to remain in power ad infinitum.

In sum, it is imperative that the African continent strengthens instruments (such as national, regional and continental courts) that prevent and punish impunity. However, what happens in the interregnum when such courts do not exist and who can vouch for the surefire impartiality of such organs if they do exist? Emmanuel Matambo is research director at the Centre for Africa-China Studies, at the University of Johannesburg.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.