On 8 March last year Mbali, my beautiful 12-year-old daughter, slipped away as I held her on my chest and my family and I sang to her at the Netcare Unitas Hospital in Centurion.

She was diagnosed with leukaemia in September 2016 and we had been through an arduous and at times tormenting journey of treatment, remission and relapse. Twice we thought she had come through the cancer and felt a surging joy carrying us into the future. And then, after what had seemed to have been a successful bone marrow transplant, an unidentified illness, a side-effect of the chemo, radiation, transplant and Covid that she had contracted while in hospital, crept into her little body leading to hundreds of agonising hours, watching her slowly change through the weeks in the ICU into someone barely resembling my beautiful, vibrant, teasing, laughing daughter.

Her father, Mdu, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in 2004. At first it was largely a theoretical thing. There was an occasional stumble during a golf game, visits by a nurse to inject him with Avonex until he learned how to do it himself, an occasional night at the hospital for meds that were given by IV. Life was still normal though. We had been together a year when the diagnosis came and married in 2006. We had two girls, Nandi and Mbali, and divorced in 2013. He had acquired other children during the marriage.

It was during the lockdowns in 2020 that I first came to see that Mdu was really sick. Almost imperceptibly at first his gait had become unsteady. He sat differently. His movements were no longer effortlessly graceful. The whisky and beer he had once enjoyed were now replaced by tea and coffee. There were frequent visits to the bathroom. He loved golf and had always walked the course. Now he had to use a golf cart. In time even the up and down into and out of the cart and the swinging of the club became too much. He never lost his charm though. There was always a joke and a rakish glint playing around his eyes.

The man I had met, fallen in love with and married, the man who fathered my daughters, was becoming someone else, something else, his body changing in front of my eyes. The girls couldn’t understand why the first thing he would do when he took them to a mall was to grab a trolley. I had to explain to them that their father was a proud man and that he preferred to use a trolley rather than a walking stick. When he wasn’t holding himself up with a trolley he used a golf club rather than a walking stick.

This irked me because I was scared that he didn’t have enough balance and might fall and hurt himself. But I realised that it was a way for him to hold on to the person that he had been, the man that he had been. The debonair, charismatic, well-travelled and well-spoken man that he had been was now in a battle against his own body, a battle that, in time, he could only lose.

When Mbali was first sick with leukaemia, from 2016 to 2017, I would spend the days at the hospital with her and Mdu would come to the hospital in the evenings after work and sleep with Mbali so that I could go home and be with Nandi. When the cancer came back in 2022, Mdu tried to do the same. I was grateful but his body would no longer allow him to be fully functional in the small confines of a hospital ward and we had to appeal to him to take care of his health. His mother and my sister stepped into the gap. But almost every day he would come, tap-tapping on his upside down golf club, to check in on Mbali.

Mbali’s illness and eventual passing was indescribably hard for both of us. For any parent the loss of a child brings on the rawest, deepest pain a human being can experience. It is a wrenching and tearing of the soul that can never heal. I think it was harder for Mdu though because he realised that he would never get the opportunity to correct the mistakes he had made by being a mostly absent father. He loved his daughters. But he had acquired three other children along the way and that changes how a father can relate to and be available to his children.

As children grow older they start seeing things through their own eyes. They visit friends and see worlds that are not like theirs and wonder why. You can do what you can to protect your children but divorce, “love children”, “baby mamas”, and unpaid maintenance inevitably get messy.

Mdu visited Mbali’s grave almost every week. He was trying, I think, to put things right with her.

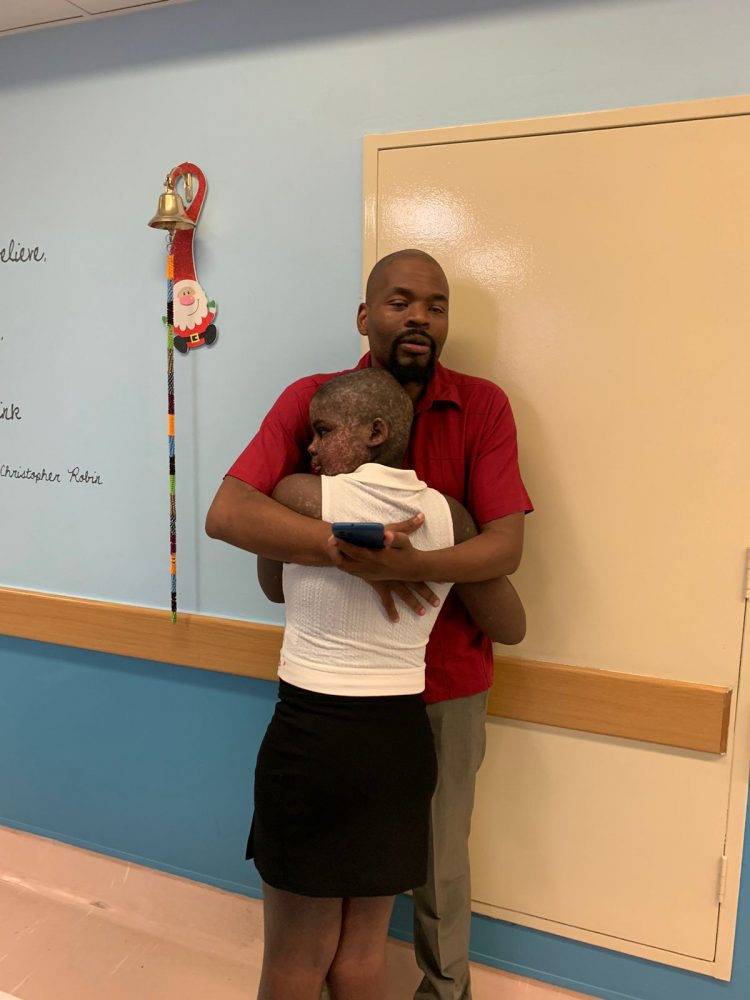

Mbali and Mdu. Photo supplied

Mbali and Mdu. Photo supplied

On 16 January Mdu was admitted to Mediclinic Kloof Hospital for pain in his chest. It turned out that he had pneumonia. His heart was already enlarged due to the immunosuppressant medication that he had to take to stop the spread of the MS. He was then diagnosed with Aspergillosis. This was to be the start of a long list of infections he would get while in hospital.

He was admitted to High Care and a day later to ICU. One day my chosen sister, Tersha Fortune, who had been by my side through all the trials and tribulations of Mbali’s illness, came with me to visit Mdu while he was still in a general ward. When we walked in he was sleeping but he had a radiant smile on his face. We woke him up. He chided us saying we had disturbed his beautiful dream, a dream where he had been talking to Mbali. “Mbali,” he told us, “was very happy to see me.” I couldn’t stay in the room and be present in the moment. I left to find the nurses because he was breathing erratically while the container with the sterile water used for humidification was empty and there was no saturation monitor.

At one point while in ICU he seemed to be getting better and was being weaned off the ventilator. He was able to sit up for three or four hours on lower oxygen. One day I was able to speak to him, to let him know that I was sorry for my part in our failed marriage and that I forgave him for his part. I was able to tell him that I was not and had not been angry with him for a long time. I asked him if he was still talking to Mbali in his dreams. He nodded.

That was the day I accepted that he was going to leave us. Being able to right things with him gave me a sense of peace. It was still a shock, though, when a day later I called the hospital to check how he was doing and was told to get to the hospital urgently, and to tell his parents to get there as soon as they could. Mdu’s lungs had filled with fluid. He had what is called Adult Respiratory Disorder Syndrome (ARDS). He had to be fully sedated and ventilated again.

The doctors were not optimistic, all the meds that could be given were being given. It all felt very similar to Mbali’s last moments. The hospital smells and the sounds. The bright sterile lights. The whispers. The looks from the nurses and doctors that don’t linger. The answers to your questions that never quite give a real answer. The pauses in those answers that you are supposed to fill in yourself. This is how it goes. This is what death in a hospital is like.

I have become fluent in it all. One of the sisters in the ICU ward where Mdu was being treated assumed I was in the medical field because I knew what questions to ask, how to read the machines and the blood test results and what the different ventilator settings meant.

When you are sitting beside an ICU bed again, losing one person so soon after another, all the grief and pain that you have contained surges up again. One thing was different though. When you are a mother losing a child your role is clear. Your role is not clear when you are an ex-wife losing the father of your children, a man who also became the father to other children.

Are you family? Should you be at the hospital? Do you have the right to be distraught? Do you have a right to expect to be involved in the arrangements for the funeral even if not for yourself but on behalf of your children, the one still living and the one who has passed from this world?

Ten days after I had been urgently summoned to the hospital a call came from the hospital in the early hours of the morning. This was to be the final call.

Mdu told his friends that he wanted to be laid to rest next to Mbali. This did not happen but I do know that they are together now.

Nontobeko Hlela is a research fellow with the Institute for Pan African Thought & Conversation and a PhD candidate in the department of politics and international relations at the University of Johannesburg.