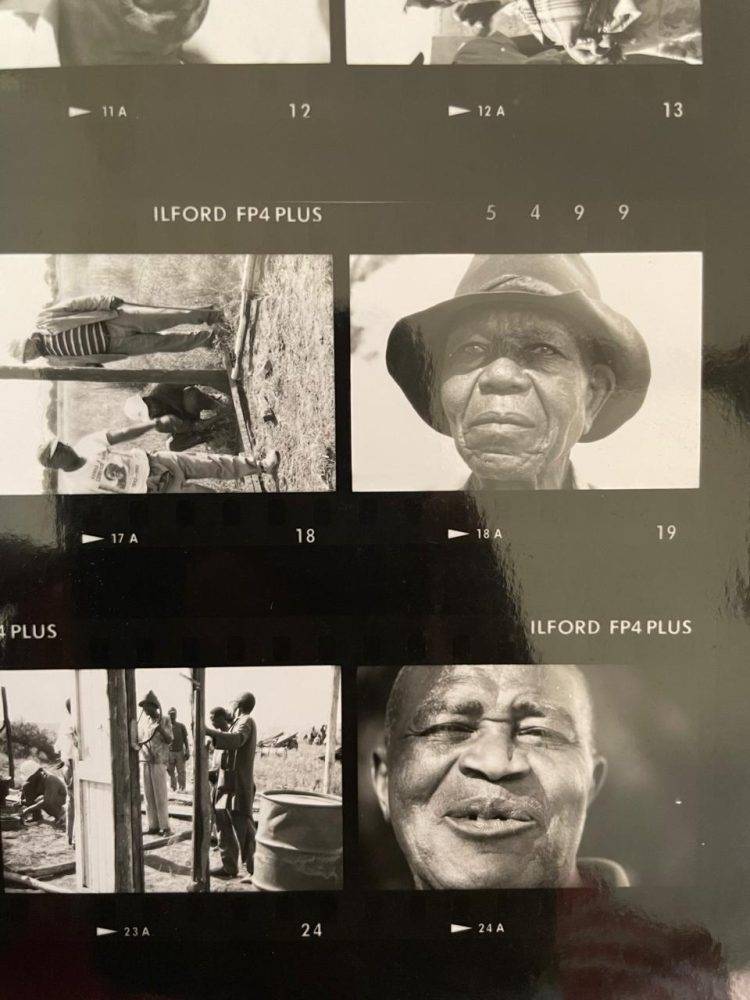

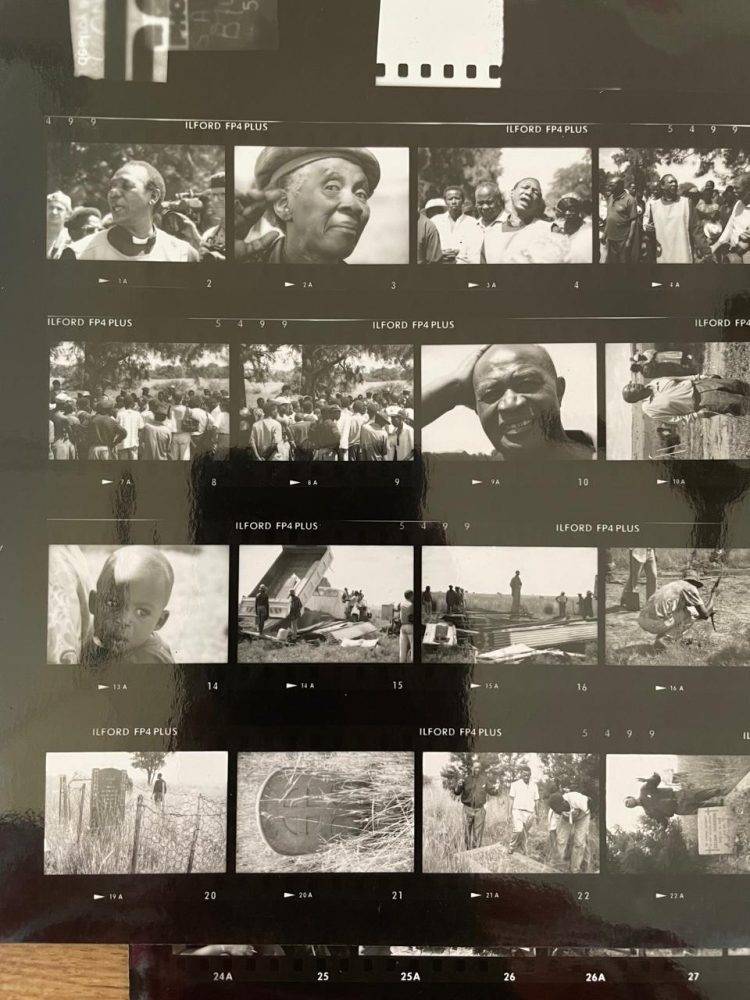

A photojournalist by formal training with a diploma in journalism and media studies, Mbulelo was a self-made intellectual and creative. Photo supplied

In today’s corporate academia and commercial journalism preoccupied with international Nobel Peace accolades, we sometimes gloss over the down-to-earth struggles for liberation waged by grassroots revolutionaries. Mbulelo Linda (1959-2024) falls in this category of activists, who grasped the value of making humble contributions for the broader objective of defeating white racial capitalism in South Africa.

A photojournalist by formal training with a diploma in journalism and media studies, Mbulelo was a self-made intellectual and creative who refined these skills from political education obtained in prison and in local struggles.

He was born into difficult black working-class conditions at the peak of apartheid violence in KwaZakhele in Gqeberha. It was during this time that he was arrested in Grahamstown by the apartheid regime for his involvement in the national 1976 student uprisings. The other unknown aspect of his life is that he once dropped out of school during his teenage years to look for a job to support his parents, siblings and relatives. These socioeconomic conditions shaped his political consciousness, and he began his lifelong commitment to the struggle against apartheid as a member of the ANC and labour federation Cosatu.

Mbulelo began work sweeping and mopping floors in white-owned businesses in apartheid Port Elizabeth. Then his grandfather, Philemon Barney Linda, who was a general worker in The Herald’s building, found his grandson a similar job there.

It is at this job where Mbulelo would quietly develop and sharpen his intellectual rigour by reading political literature on the labour movement. He would participate in discussions with fellow workers and his supervisors about sports and the politics of the day. It was through these discussions where his writing and insights were discovered and he became a photojournalist for the newspaper.

He used his pen and camera to expose the unspeakable crimes of the apartheid regime. This epistemic technique of struggle is similar to the work done by the likes of Sam Nzima, the photographer of the lifeless body of Hector Peterson held by a running Mbuyisa Makhubu alongside Antoinette Sithole on 16 June 1976 in Soweto.

Anti-apartheid photographers such as Nzima, Peter Magubane and Mbulelo presented unavoidable visuals of the cruelty of apartheid. Their photographs reminded the world that apartheid was not an abstract project, but rather a locally executed crime in each township street and in each household. It was specific and aimed to dehumanise black people, who today still carry the trauma.

Mbulelo continued his labour of love into the late 1980s, reporting and photographing black people in sports, political activism, business and the arts. In 1989 he married his lifelong partner, Nomfundo, and was blessed with a family of five children. I was fortunate to meet one of them, his daughter Ntombovuyo, who is now a 31-year-old researcher, creative and intellectual activist. I met her in the picket lines of the student movement fighting for decolonised education. I might not have met Mbulelo personally, but through Ntombovuyo I got to see the heritage of his insights, values, principles and commitment to the liberation of black people.

Ntombovuyo wrote about her father: “What I liked the most about my relationship with my father, is that we found each other interesting, we were curious about the way we thought about things, discourse was our shared love language.”

In the post-1994 epoch of South Africa’s independence, Mbulelo continued with his struggle for liberation. He was instrumental in the founding of the Government Communications and Information Systems, a division in the state intended to craft public discourse about the ideas and work of the democratic government. He then served in communication management positions of the public service in the Eastern Cape until his retirement. He remained highly critical about the unfinished struggle to end the colonial white settler project of racial capitalism in South Africa.

His last opinion piece written in July 2021 in The Herald newspaper, during his illness, he called on young people to vote because many black people still live like animals and human dignity remains a privilege enjoyed by white people. He wrote: “After 27 years of constitutional democracy, we still find poverty concentrated in the slums of the townships, no white people would like to live like that, ever.” Evidently, Mbulelo was disappointed with the current South Africa but was equally optimistic and aware of the power of the youth to change the course of history as his generation had done.

Mbulelo will be remembered as a humble father, husband, uncle and grandfather, a people’s creative, intellectual and journalist.

Joe Davidson, internationally renowned journalist and friend of Mbulelo wrote: “Mbu was my friend since 1986. I was a journalist from Washington covering the apartheid struggle in the Eastern Cape. Mbu was among those who made South Africa feel like a second home to me. We’ve kept contact all these decades. He was a good and decent man and I’ll never forget him.”

Today, we must dip the flag of our nation and thank his family for lending us this towering revolutionary. May his soul rest in power. Hamba kahle Mkhonto.

Dr Pedro Mzileni, a senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Zululand, writes in personal capacity.