(John McCann/M&G)

The 10th of December marks the 28th anniversary of the signing of the Constitution into law. Regarded as one of the most progressive legal documents in the world, the Constitution provides a strong foundation for democratic governance.

Its emphasis on transparency, accountability and justice also provides a critical framework to prevent and limit corruption.

But, over the past three decades, the practical effectiveness of these safeguards has been uneven.

High-profile corruption cases and systemic inefficiencies in prosecution capability and efficacy have eroded public trust, raising questions about the extent to which the Constitution has fulfilled its role. Understanding its strengths and weaknesses is essential to support anti-corruption efforts in South Africa.

Section 1 establishes transparency, accountability and responsiveness as foundational values, while Chapter 9 institutions such as the public protector and auditor general ensure independent oversight. The Bill of Rights empowers citizens with access to information (section 32) and just administrative action (section 33), fostering public accountability through participatory governance. The judiciary further reinforces these safeguards, as seen in landmark rulings such as the Nkandla case, which upheld the public protector’s authority and executive accountability.

Despite this robust framework, the implementation of these principles has faced significant hurdles.

State capture, during the Zuma administration, exposed systemic corruption and weakened key institutions such as the National Prosecuting Authority.

Political interference has undermined the independence of oversight bodies, reducing public trust.

Corrupt officials often evade accountability because of delays in judicial processes and weak enforcement mechanisms, while whistleblowers lack adequate protections. Socio-economic inequalities exacerbate these problems, creating fertile ground for corruption in service delivery and procurement processes.

The evidence is clear that grand corruption enabled corruption everywhere, and vice versa, creating a vicious cycle that has proved difficult to stop.

The very institutions that were designed to deter corruption have become weakened through systemic corruption.

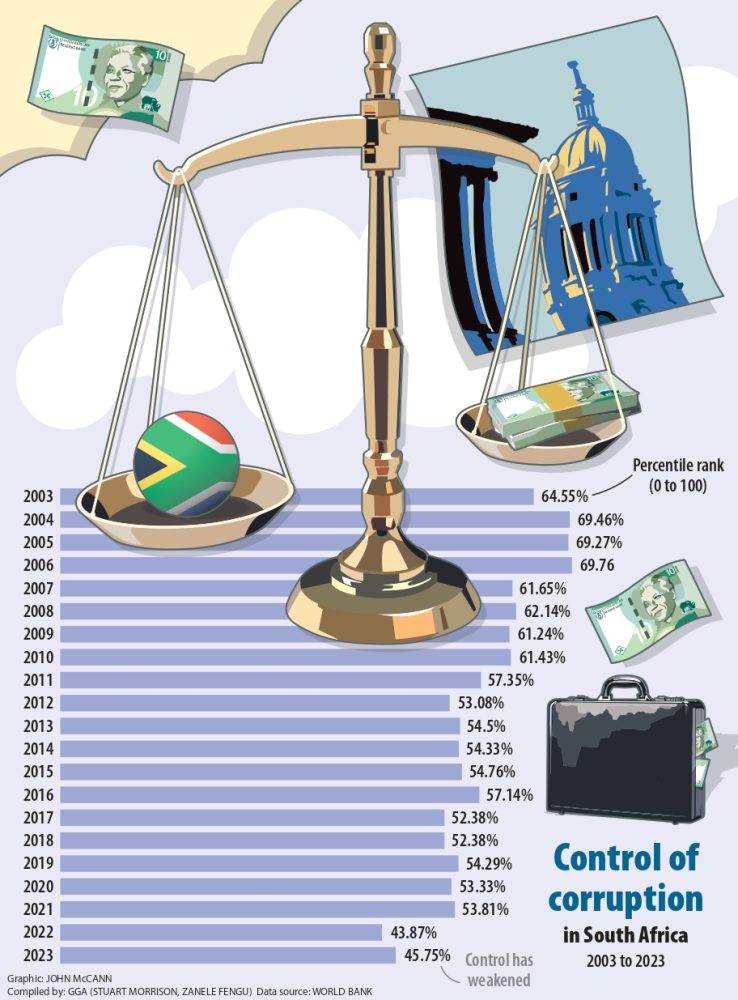

Public perception reflects these shortcomings. According to the World Governance Indicators, which measures perceptions about the quality of a country’s governance, the ability of South Africa’s institutions to control corruption has sharply declined over the past two decades.

In the early 2000s South Africa scored close to 70%. We’ve since declined to 45.75% in the latest iteration of the indicators. This decline signals ongoing scepticism about the government’s ability to tackle corruption.

This raises the question of the extent to which the constitution has been able to effectively safeguard against corruption and what to do to address the limitations.

While the Constitution on paper provides a solid foundation for combating corruption, the country’s efforts have been limited because of systemic failures in implementation and enforcement.

A constitution is only as valuable as a country’s ability to uphold it. In itself, it cannot prevent failure such as those that have afflicted South Africa.

These failures, as highlighted in the Zondo state capture commission, can be summed up broadly into three issues: political interference, lack of accountability for political leaders and inadequate funding and capacity.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

According to section 181 of the Constitution, key oversight bodies such as the public protector, the auditor general and the electoral commission need to be fully independent and perform their duties without “fear, favour or prejudice”. But the ability of these Chapter 9 institutions to protect citizens against government corruption has been limited by political interference.

For example, the public protector’s office has been subjected to various kinds of political pressure ranging from campaigns to discredit the office to the politicisation of the public protector both in appointment and function. This undermines the values of accountability enshrined in the Constitution and compromises the independence these institutions are meant to have. This has a direct effect on the implementation of the Constitution.

Section 42 of the Constitution emphasises that the National Assembly exists to represent the people of South Africa and parliamentarians are so entrusted by citizens to hold other branches of the government accountable. But this is undermined by political parties being unable to hold their members accountable, especially those elected to represent South Africans in the legislature.

Patrick Kulati, chief executive of Good Governance Africa, has recently argued that there is an accountability crisis taking place in the political sphere.

Political parties fail to effectively hold their leaders accountable. This undermines the Constitution’s ability to be an effective safeguard against corruption because it limits the processes of accountability fundamental to any democracy.

For this reason, reconfiguring our electoral system to enable greater levels of accountability should be a priority of the present grand coalition in power.

One of the key issues that limits the implementation of the Constitution as it pertains to corruption safeguards is the shortage of resources and personnel to staff key branches of government and institutions.

This is best seen with the problems the judiciary faces in being an effective arm of justice. The judiciary has been courageous and effective in upholding accountability and limiting as much as possible the entrenchment of corruption. But its struggle with problems such as prolonged case backlogs is symptomatic of the resource and capacity issues the judiciary faces.

These implementation and capacity gaps allow corrupt actors to operate with impunity, weakening public confidence in anti-corruption measures that ultimately undermines our democracy.

To address the implementation gaps which limit the Constitution’s framework being translated into action, there needs to be a stronger commitment among leaders, MPs and government officials to addressing corruption.

Doing so will rebuild the public’s trust in the various state institutions and its leaders, as well as making progress towards realising the aspirations of the Constitution.

But this commitment needs to go beyond speeches and PR work; it requires intentional and targeted actions which will address some of these gaps.

This should include prioritising the implementation of the Zondo commission recommendations. Particularly, recommendations that promote and rebuild public trust in the state, such as the adoption of the National Charter Against Corruption and those that address the key accountability gaps such as the establishment of a permanent anti-corruption commission should be prioritised.

Furthermore, there needs to be greater effort to strengthen the independence of Chapter 9 institutions.

This includes greater involvement from civil society and the wider public in the appointment of key positions in these institutions such as the public protector and improved resource allocation to ensure that these institutions are able to fulfil their constitutional mandates.

Last, there needs to be greater efforts to realign the state, the public administration and private sector to the values outlined in the Constitution.

The Constitution is the “people’s document”, because it highlights the desires, hopes and dreams of South Africans.

But there is a growing sentiment of frustration at the slow pace at which these ideals are being realised.

This calls for a moment of critical reflection by the public and private sectors to unpack the extent to which they align with the constitutional values and, more crucially, how to realign themselves to these values.

The Constitution’s effectiveness as an anti-corruption safeguard depends not just on its provisions but also on the commitment of political leaders, the integrity of institutions and active civic participation. Without these, the Constitution’s progressive ideals risk becoming distantly aspirational rather than immediately actionable.

Stuart Morrison is a data analyst at Good Governance Africa. Zanele Fengu is a legal researcher specialising in human rights, governance and anti-corruption.