Wastewater treatment processes cannot remove the bioactive compounds, underlining the need for technological advancements. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

The World Economic Forum notes that water scarcity is a key priority on the sustainability agenda. Water availability is not only needed to meet people’s day-to-day needs but contributes significantly towards a country’s overall health, economic growth and development.

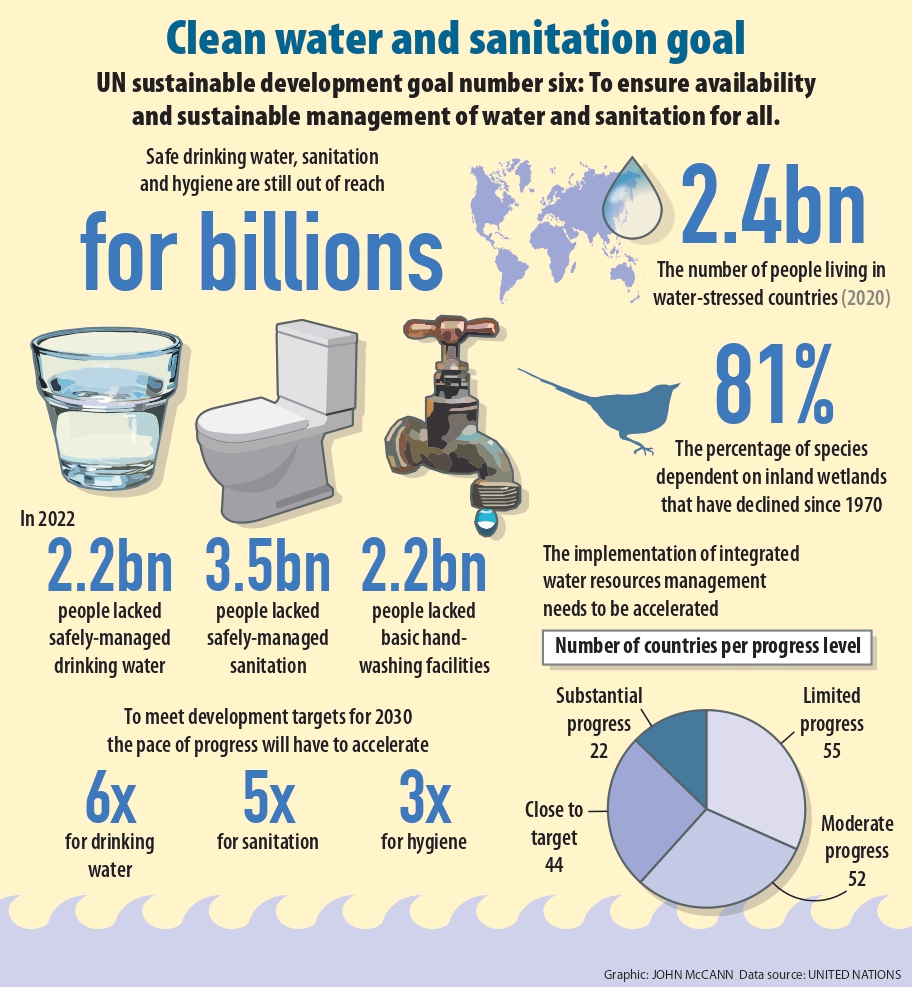

Local governments, which are positioned closest to the residents, play a critical role in the realisation of the UN’s sustainable development goal six that seeks to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

Section 77 of the Zimbabwean Constitution highlights every citizen’s right to food and water, and particularly to “safe, clean and potable water”.

The direct effect that the provision of safe, clean and potable water has on the right to sufficient food and healthcare, among others, makes it imperative for the state, through its local government arm, to “take reasonable legislative and other measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right”.

But, for a majority of residents in parts of Chitungwiza, Epworth and New Dzivarasekwa, it is not the local government but residents themselves who have adapted to ensure access to safe drinking water and other household uses.

Good Governance Africa (GGA) researcher Helen Grange, focusing on South Africa, observes this adaptation resulting from “the breach left by failing local government services, [in which] citizens have been making alternative plans for years … digging boreholes to tap underground water and purchasing water tanks to help them get through water outages and throttling”.

The issue of insecure access to water is not unique to South Africa and Zimbabwe. It is a global problem as reflected in the United Nations 2023 Sustainable Development Goals Report on Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, Waste and Electricity Services in Healthcare Facilities: Progress on the Fundamentals.

The report states that globally, safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene in healthcare facilities was still out of reach for billions of people in 2022. Within this context, 2.2 billion people still lack safely managed drinking water and 3.5 billion lack safely managed sanitation. That is nearly half the world’s population. The report euphemistically underscores that progress will have to be accelerated if the 2030 agenda is to be met.

In Zimbabwe, urban local governments across the country have, for the past two and a half decades, been marked by deepening economic decline while battling a diversity of problems on their service delivery mandates.

GGA researchers Nnaemeka Ohamadike and Ian Palmer have analysed how, for example, “Harare carries a high degree of service provision responsibility, with legislation devolving a wide range of key functions, including infrastructure-intensive services — water supply, sanitation, waste management, urban road infrastructure — and social services, notably healthcare and education.”

Faced with population growth, rapid urbanisation and climate change, among other crises, local authorities in Zimbabwe have seemingly abrogated their constitutional mandate.

Yet it has not only been these external issues, but bad governance characterised by mismanagement, corruption and institutional breakdown.

Residents in and near Harare have been left to take care of their own water and sanitation services, as well as refuse collection. People’s water scarcity adaptation measures include buying water for daily use from enterprising water vendors, pooling resources to drill for water and digging water wells at their homes.

These measures, some of which are unregulated, such as the digging of household wells, pose a health threat to a country already battling waterborne diseases such as cholera.

On 5 April 2025, GGA spoke to residents to better appreciate the depth of their water woes. Chitungwiza is a municipal town, roughly 25km from Harare, with an official population of 374 279. Informal estimates place the population at 650 000.

Respondents said that since July 2024, they had received water from their local authority only once, on 31 March 2025, a day when there were threats of a nationwide protest march.

One respondent said she relies on buying water to meet her daily drinking needs because water from the local authority is not safe.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“Our local authority water has never been safe for our drinking needs. Further to that, its supply is erratic, hence unreliable,” she said. “Apart from 31 March this year, we last received council water here in Tamuka, also known as C Junction, in July last year. We rarely receive local authority supplies and when we do, the water is rusty and often smelly, as if it has passed through the sewage system.

“We simply do not drink our tap water. On the rare occasions that we receive it, we collect it for other non-drinking, non-cooking purposes. For drinking water, we buy from those with safer sources such as boreholes and mobile water bowsers. The water, depending on demand, costs one US dollar for anything between six and eight buckets.”

Respondents identified cases of underground water contamination, such as that caused by ageing sewer pipes affecting drinking water provided by local authorities and residents’ unregulated water wells. As a result, children contracted diarrhoea.

New Dzivarasekwa, as its name denotes, is one of many settlements mushrooming around Harare as a result of rapid urbanisation. Much of it does not receive water from the City of Harare.

Those residents who can afford it have pooled their money to drill co-owned boreholes, enabling them to secure water for their household and other uses.

One respondent, who is also a teacher at a local school, beamed with pride as she explained how they had come together to embark on this life-saving measure.

“We pooled our financial resources for the drilling and purchase of implements and this tank. We even had the quality of our water tested for any likely contaminants and it has been certified safe for use, especially for drinking,” she said.

“We were also informed that our borehole’s water supply is quite prolific and can cater for up to 12 households.”

An Epworth resident commented: “Water is not a problem in Epworth, mari yako chete, as long as you have your money, you can get it anytime you need it.”

While the resilience and ability of Zimbabweans to adapt is commendable, central and local governments need to step up to their mandate to ensure water security through good water governance, anchored in appropriate, solid legal and policy frameworks.

The World Economic Forum notes that because water and national security are intrinsically linked, it is critical for policymakers and the private sector to come together to ensure the safety of the communities they serve.

GGA researcher Leleti Maluleke, writing on water insecurity in South Africa, offers a useful insight: effective water resources governance is key to breaking cycles of poverty and setting communities on the path to attaining sustainable development.

Sikhululekile Mashingaidze is the lead researcher in Good Governance Africa’s Peace and Security Programme.