December 8 2018: Paul David signs a Consulate Six poster at an In Conversation with Paul David tribute event held at the 1860 Heritage Centre in Johannesburg. (Photograph by Satish Dhupelia)

LONG READ

Nothing quite reflected the ANC’s break with its liberation ideals than one of the final political acts of Devdas Paul David, the human rights activist and lawyer who died at his home in KwaDukuza (Stanger) on the KwaZulu-Natal north coast on August 13 2020.

Three years before David’s long illness confined him to his bed, his deep sense of justice caused him to stand up – as he had always done – for his community.

The ANC-run KwaDukuza Municipality had contrived to sell the town’s sports complex, which included a cricket oval; a football ground; a public swimming pool; tennis, netball and volleyball courts; and a nine-hole golf course to Vivian Reddy, a businessman and crony funder of former president Jacob Zuma.

Reddy had bought the 27 hectares of public land for the paltry sum of R9 million to develop a shopping mall the town appeared not to need. The market price of the land was independently evaluated to be worth, conservatively, approximately R60 million.

Despite semi-retirement, David, a member of the ANC underground whose scope of political activity since the late 1950s included student politics, civic activism and being president of the Natal Council on Sport (Nacos), lent his lawyering skills to the Concerned Citizens Group (CCG), which was contesting the sale of the land and its development. He worked largely pro bono, reluctantly accepting money when it was pressed into his hands, and for much less than the value of his legal assistance – as he had often done during his career as an attorney, which spanned more than half a century.

He also rendered leadership and guidance burnished in the anti-apartheid struggle, where his credentials were impeccable.

At stake for the lawyer who, in his younger days had played for two storied sporting institutions in the town – Swans Football Club and Royals Cricket Club – was not just a deal that appeared dodgy, but the ripping out of the very soul of this working-class community where paper and sugar milling had been historical drivers of employment. It was to these grounds that people turned during their time off.

Industries had shifted and unemployment risen, but the Stanger Recreation Ground and Stanger Country Club grounds remained a community focal point that transcended race and class.

An attempt to urgently interdict the mall construction failed on a technicality and, despite a Promotion of Access to Information Act application, the municipality refused to hand over documents vital for the CCG’s case to continue, stalling the matter until the strip mall became an inevitability.

Reddy, in turn, counter-sued David and the CCG members – comprising retired school teachers, former sports administrators and local businesspeople – for R28 million. The odious Reddy claimed this was for defamation and loss of earnings.

The battle lines were drawn. They had cast David – an activist with a history in the Stanger Ratepayers Association, the Durban Housing Action Committee, the Natal Rates Campaign, Natal Indian Congress (NIC), ANC underground, United Democratic Front (UDF), Release Mandela Campaign, the National Association of Democratic Lawyers, Nacos and the South African Council on Sport – on one side with his community.

On the other side were powerful ANC leaders, all political juniors to David, who stymied transparent government by flouting the legislation that allows ordinary people to participate in democracy. These were public office bearers who had debased a vital interface between citizens and the state so as to push through a deal with a capitalist who was crass enough to try to intimidate pensioners with the threat of bankruptcy.

David, recently described as “the activist’s activist” by his underground comrade, Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan, had, by staying true to his political convictions and standing with the small people – as he had always done – illuminated one of postapartheid South Africa’s most vexing questions: What has power done to the ANC?

David’s “disillusionment” with what the ANC had become was a theme repeated often at the online memorial held for him on 16 August, where comrades from across the political spectrum spoke glowingly of someone possessed with an unstinting political conviction that demanded selflessness over selfishness.

It was an open secret that David had requested a private funeral so that no politicians would hijack it. A straightforward man with little time for hypocrisy, he would have been unable, even in death, to stomach the platitudes that now accompany farewells to political elders, where empty promises to emulate the dead are not matched by the corrupt actions of the living.

“Paul David understood that sacrifice cannot be compromised by greed,” Gordhan said at the memorial.

Undated: Sixteen members of the United Democratic Front were accused of treason in the Pietermaritzburg Supreme Court. Paul David is standing third from the left in the front row. (Photograph supplied by UKZN Archives, Documentation Centre)

Undated: Sixteen members of the United Democratic Front were accused of treason in the Pietermaritzburg Supreme Court. Paul David is standing third from the left in the front row. (Photograph supplied by UKZN Archives, Documentation Centre)

Reverend Frank Chikane, one of the co-accused alongside David in the 1985 Treason Trial in Pietermaritzburg and the director general in former president Thabo Mbeki’s office, noted that the quest for a “non-racial, non-sexist, equal society” informed David’s every action: “That history and tradition represents the opposite of what we are today. We are not the society we struggled for. We are not the nation we struggled for … We are trapped in a society of such inequality where leaders rob the nation and the poor of what they should have, corrupt to the core.” This left David, despite his understanding of the challenges postapartheid South Africa faced, deeply unhappy, Chikane added.

CCG chairperson Haroon Mahomedy told New Frame: “With all the sacrifices Paul made, with his commitment to the struggle, you’d expect the ANC in KwaDukuza to seek him out for advice, but there was no such thing like that. He never sought out positions, but he did have a great institutional memory and vision which was ignored by the local ANC and you see the consequences of that in a community which is split and infrastructure that is broken down.”

Political awakening

Devadas Paul David, the eighth child of Violet and Simon David, was born in Pietermaritzburg on 26 August 1940. His sister, the formidable ANC activist and author Phyllis Naidoo, noted in her book Footprints in Grey Street that their mother “was greatly enamoured with this beautiful boy who looked like her father, whom she last saw when she was eight years old. Despite our poverty, he was the most photographed baby.”

Simon David was known across KwaZulu-Natal as a strict disciplinarian and a no-nonsense school principal, and later, an inspector, whose promotions led him to teach at various schools in the province. His son followed him and was educated at St Anthony’s School in inner-city Durban’s Warwick Avenue, then to Umzinto and finally Verulam High School where he matriculated in 1958.

Students at Verulam High School took a keener interest in the 1955 Treason Trial when it was announced at a school assembly that local attorney Ismail Meer was one of the 156 accused.

According to Footprints, David participated in the 1957 school stayaway called by the South African Indian Congress’ Monty Naicker. It was also the year when “he met [Karl] Marx through MD Naidoo”, a member of the South African Communist Party, who would marry his sister Phyllis a year later.

This meant that even as a teenager, David had access to circles that included Govan Mbeki, lawyer Duma Nokwe and other titans of the anti-apartheid struggle.

In Footprints, David recounted meeting Mbeki for the first time: “When I asked Uncle Gov what could I do to become political? ‘You are already there,’ he replied.”

Initially enrolled for a Bachelor of Arts degree in the blacks-only section of the University of Natal, David moved to the medical school in Umbilo before finally settling on obtaining a law degree.

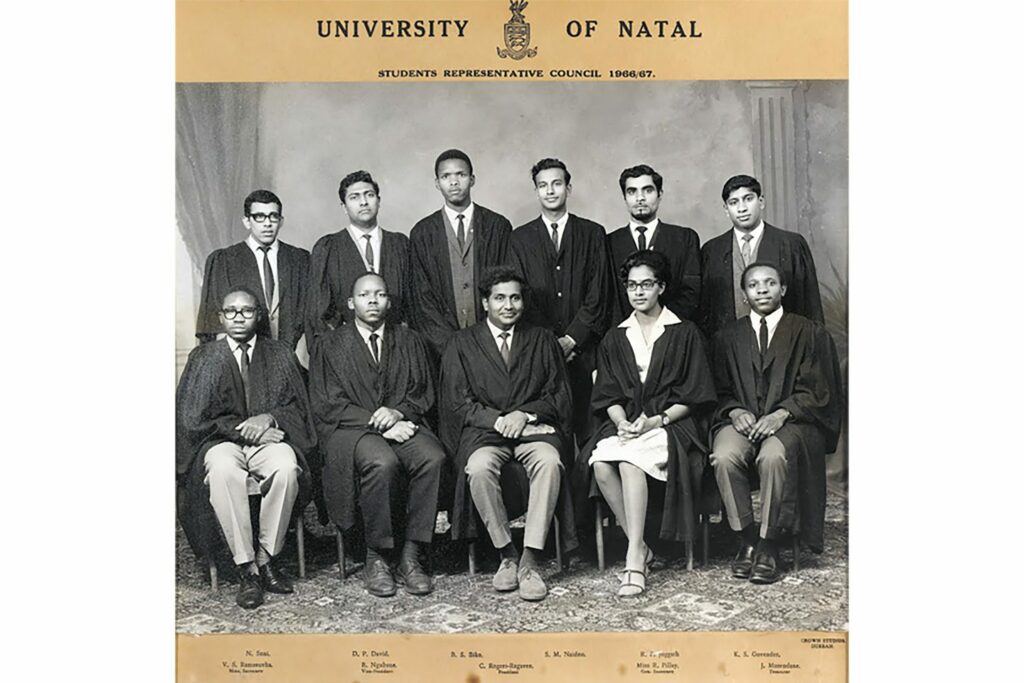

Undated: The 1966/67 Student Representatives Council of the black section of the then University of Natal. Paul David is standing second from left. (Photograph supplied by Paul David Archives)

Undated: The 1966/67 Student Representatives Council of the black section of the then University of Natal. Paul David is standing second from left. (Photograph supplied by Paul David Archives)

At university, he served on the Student Representative Council alongside Steve Biko, the black consciousness leader and founder of the South Africa Students’ Organisation and the Black People’s Convention. Theirs was a friendship that endured until Biko’s murder by the apartheid police in 1977.

“We were buddies! His death plagues me still!” he told his sister in Footprints.

Inclusive politics

This experience and friendship informed David’s inclusive approach to the various strains of anti-apartheid politics forming in the country, especially after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and the banning of the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC). David remained aware that a more united front against the regime offered the best chance of overthrowing it.

Lechesa Tsenoli, deputy speaker in the National Assembly, said David’s background as a lawyer fed his approach to political inclusivity. Along with David, Tsenoli was part of the founding leadership core of the UDF, which was formed in 1983 to bring the various anti-apartheid associations and political formations together.

“He was inclusive because he was such a confident debater,” said Tsenoli. “Paul had a great ability to chair meetings, to crack a joke, to goad people at the right moment. I admired this trait because it was an important skill in a civic movement where you couldn’t alienate people who may have disagreed politically with you but agreed with you on local and civic issues which were being raised.”

Krish Govender, the former KwaZulu-Natal attorney general and a black consciousness activist in his youth, remembered David’s lack of political dogmatism: “Paul embraced every political ideology, not in terms of support for all, but an appreciation of ideological standpoints. He welcomed people regardless of whether you were PAC, Unity Movement or BC [black consciousness], and he attempted to take everybody forward even if you came from different political homes.”

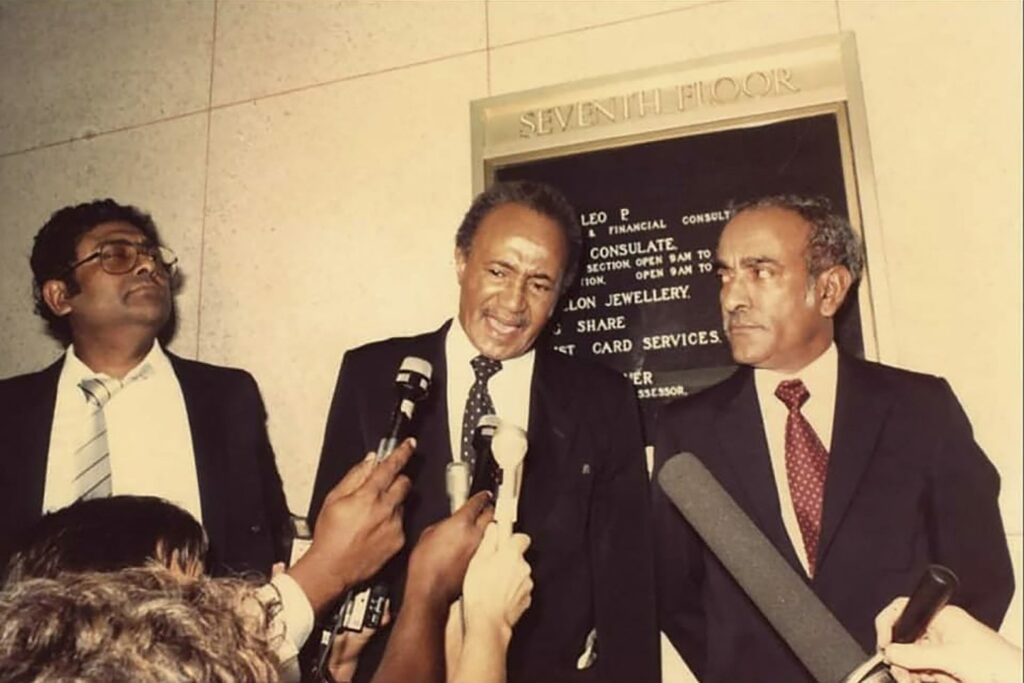

Undated: Paul David, Archie Gumede and Billy Nair pictured outside the British Consulate offices. (Photograph supplied by 1860 Heritage Centre)

Undated: Paul David, Archie Gumede and Billy Nair pictured outside the British Consulate offices. (Photograph supplied by 1860 Heritage Centre)

Govender was part of the Theatre Council of Natal (Tecon), which had been formed in the early 1970s by another black consciousness stalwart, Strini Moodley. He remembers travelling around KwaZulu-Natal to small towns and university campuses to perform plays such as Antigone, which Moodley had “adapted to the modern-day struggle context” and Into the Heart of Negritude, a series of poetry recitals accompanied by the avant-garde Malombo Jazz Trio led by the singular guitarist Philip Tabane.

The troupe’s performances in Stanger, where David had set up his practice after being admitted as an attorney in 1968, would inevitably end with dinner and a late night at his house: “Many people in the Congress movement weren’t receptive to black consciousness. They saw us as anti-white and racists, but Paul worked closely with us … He was a ‘Charterist’, a ‘Congressite’, but if you saw him with us, you would think that he was one of us. He understood the value of getting the message out there and he saw value in everything: in poetry, in jazz, in the theatre and the arts, in their power to conscientise people.”

According to John Samuel, a fellow activist and friend of David’s since high school, “he intuitively understood the importance of organising … and he had a deep sense that you had to take the people with you”. Citing Antonio Gramsci’s three revolutionary pillars – construction, organisation and persuasion – Samuel said that “Paul’s political involvement was marked in a very strong way by these characteristics”.

By 1971, David had become chairperson of the Stanger Ratepayers Association. He was also integral to the revival of the NIC that year, too.

Former Constitutional Court justice Zak Yacoob said it was clear to David that – with the continued banning of the ANC and PAC – “the re-establishment of the NIC was not about the advancement of Indian people, but about the advancement of all African people”.

Yacoob said that on a personal level, he was grateful to David for advancing his career. “When I became an advocate in 1973, the thinking was that blind people had no brains – something that still persists to some degree today – and I found it very difficult in getting any work. Paul was the first attorney from Stanger to brief me, and one of the few people who did that. Thankfully, others followed.”

Decades of violence and resilience

The early 1970s had birthed the seminal Durban Moment, when trade unionism and black consciousness were in the ascendency, to the soundtrack of jazz and poetry.

Vino Reddy, another black consciousness activist and member of Tecon, described those times as “incredible, despite the bannings and the torture. We knew who we were and we knew who the enemy were, that was significant. You would have wonderful debates and discussions, which started on the street and ended up at the Revelation Record Library or the Lotus Club in town.”

But the apartheid regime would suppress all this with bludgeoning and bullets. Schoolchildren would be shot dead in the streets of Soweto in 1976, the police murdered Biko a year later, then University of Natal academic and radical philosopher Rick Turner was assassinated in his Durban home in 1978.

It was “seed time”, as black consciousness poet Mafika Gwala observed in No More Lullabies:

What went round has come around

This time the plants will grow

and bear fruit to raise up more seed

There’ll be a refreshing persistence of the wits

Because this time

There’ll be no more lullabies

The 1980s were to prove a decade of violence, trauma and resilience for South Africans. The states of emergency, ramped-up arbitrary detentions without trials, disappearance of activists, the state’s training and funding of Inkatha’s deadly violence in KwaZulu-Natal, and attempts to divide and rule through the apartheid regime’s introduction of the tricameral parliamentary system would cast an oppressive cloud over the country.

Ordinary people would respond with increasing mobilisation and militancy. Apartheid minister of law and order Louis le Grange described those times as “a climate of revolution”.

By the early 1980s, David had, among other leadership roles in various organisations, become the secretary of the Release Mandela Campaign, which Archie Gumede led, with anti-apartheid lawyer Griffiths Mxenge installed as treasurer. The aim of the campaign was to gather a million signatures in support of the release of Nelson Mandela.

Mxenge would, in 1981, be murdered by an apartheid death squad led by Dirk Coetzee. Mxenge was stabbed 45 times, beaten with a hammer and his throat slit before his body was dumped in a soccer field in Umlazi township, south of Durban.

In an interview with then Radio Lotus, David recounted how Mxenge’s funeral coincided with that of his mother and somehow, he had managed to organise both.

Doing time

For David, the decade started with the schools boycott that led to his detention in Modderbee Prison in Benoni.

Retired high court judge Thumba Pillay remembered working with David as the legal representatives of the schoolchildren “being bashed around by security police and being arrested and so on … the mass support, across race, was growing and the situation was getting out of hand for the state. So they tried to put an end to it by getting rid of the leadership, arresting student leaders and us, their lawyers.”

For three months, Pillay and David shared a dormitory-style cell with about 40 other anti-apartheid activists from different political organisations, which “allowed us to converse with each other and discuss tactics … that was the stupidity of the apartheid state,” Pillay says with a laugh.

October 23 2016: Paul David talks to fellow struggle activist Pravin Gordhan at the funeral of ANC stalwart Mewa Ramgobin in Verulam, Durban. (Photograph by Rajesh Jantilal)

October 23 2016: Paul David talks to fellow struggle activist Pravin Gordhan at the funeral of ANC stalwart Mewa Ramgobin in Verulam, Durban. (Photograph by Rajesh Jantilal)

“Paul was larger than life, and he made detention so much easier. He had a great sense of humour and wasn’t too perturbed about our situation. He was the kind of guy that you want to get locked up with,” said Pillay.

The retired judge remembered the activists smuggling in a battery-operated television so they could watch the fight between Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Durán and other lighter moments: “We only had a couple of toilets in these communal cells and when Paul got into the toilets, he could read Shakespeare from cover to cover, that was his favourite pastime in prison,” said Pillay.

In Footprints, Naidoo noted that their father had “reared a reading family” of activists, including siblings Ben David and Sinthi Qono. One of the earliest books to leave a mark on her brother, Naidoo wrote, had strong anti-war themes; Paul Gallico’s Snow Goose and Jesus Wept, a pictorial book about the devastation of World War II. Later in high school, he found A Tale of Two Cities “extremely political”, likewise Cry the Beloved Country.

With the apartheid regime intent on setting up the tricameral parliamentary system, which allowed “Indians” and “Coloureds” a farcical, limited notion of the franchise, David’s organising and campaigning intensified.

Praveen Sham, David’s first article clerk and later partner, remembered returning home late one night in 1984 after many hours spent campaigning against the tricameral system and flopping into bed.

“At about 2am, I heard the dogs barking and a loud knock on the door. It was Paul, and it seemed the security police were on his trail,” Sham remembered. They decided that Sham’s house would be the first place the police would come to look for him, so they moved David to the home of another activist and lawyer, Riaz Meer.

David stayed there for a few days before it became apparent the police may be closing in on that hideout too. “An instruction came from high up [in the underground leadership] that Paul had to move from there. The next day, Paul said: ‘I’m just going for a little walk’, and he left and never came back. We received word that he was okay and then he ended up at the British Consulate in Durban.”

Protesting draconian laws

The occupation of the British Consulate in Durban by David, UDF president Archie Gumede, UDF treasurer Mewa Ramgobin, NIC president George Sewpersadh, NIC vice-president MJ Naidoo and trade unionist Billy Nair was a protest against preventative detention orders.

The 1980s made acute that in apartheid South Africa, the rule of law did not exist as much as rule by law did. Laws were made for oppression and to allow the apartheid state to act with impunity. Preventative detention orders allowed the police to arrest people considered a threat to law and order, with no need for the state to provide reasons for the detention or for those arrested to have access to a trial.

The six occupiers had descended on the British Consulate seeking the “protection” of that government. The occupation brought global attention to the draconian measures black people in South Africa faced every day.

David described the conditions in the consulate as “harsh and unfriendly”. They were confined to a small office, bathed in a basin and used a chemical toilet. “We slept on the carpeted floor and I taught the others how to use their shoes as pillows,” David remembered in a 2018 opinion piece.

Ramgobin, Sewpersadh and Nair left after three weeks and were immediately arrested and charged with treason. Gumede, Nair and David endured three months in the consulate.

Yacoob, who acted as one of the lawyers for the Consulate Six remembers “comrades organising food for them every day. One day, the comrade didn’t cook the chow and we were stuck. So I said let’s go down to a restaurant called the Golden Peacock, get several portions of biryani, put it into a pot and get it to the consulate. The next day we received a note from Paul: ‘The food yesterday was somewhat suspect,’ it read,” said Yacoob, laughing.

Undated: Mac Maharaj, Pallo Jordan and Paul David pictured at the Dr. Monty Naicker Exhibition launch in Durban in 2016 (Photograph by Rajesh Jantilal)

Undated: Mac Maharaj, Pallo Jordan and Paul David pictured at the Dr. Monty Naicker Exhibition launch in Durban in 2016 (Photograph by Rajesh Jantilal)

The charges of treason emanating from the occupation meant that David, Nair and the others joined 10 other activists, including Chikane and Albertina Sisulu, in the dock of the Pietermaritzburg high court in late 1984.

During David’s memorial, Chikane remembered the accused’s senior counsel, Ismail Mohamed, who would go on to become democratic South Africa’s first chief justice, telling his clients that according to the law, “we would go to jail for a very long time if this trial ended”. So, he found a “reason to keep the judge busy every day” and prolonged it until the state’s case finally collapsed and the matter was thrown out in mid-1986.

Activist, professor and scientific director at the Doris Duke Medical Research Institute Jerry Coovadia, during the memorial, remembered a photograph of the 16 accused of treason taken outside the high court in Pietermaritzburg. “Paul poses in a way with his hands folded, looking at the world, defying it to oppress him,” he observed, saying this went to the heart of his character.

A revolutionary till the end

David was an “intense revolutionary” for whom struggle against injustice was second nature. He was a humble man without pretensions, who was “altruistic” and kept faith in basic revolutionary principles, including attending a public hospital until the very end. Not for David the high-end, government-run Albert Luthuli Hospital so favoured by KwaZulu-Natal’s political elite, but the lumpen KwaDukuza Hospital down the road from his modest home.

Coovadia said he will miss David “in the struggle for a better healthcare system than the current one, which is insufficiently organised”.

December 8 2018: Paul David, Ela Gandhi and Swaminathan Gounden pictured at the In Conversation with Paul David tribute event held at the 1860 Heritage Centre in Johannesburg. (Photograph supplied by 1860 Heritage Centre)

December 8 2018: Paul David, Ela Gandhi and Swaminathan Gounden pictured at the In Conversation with Paul David tribute event held at the 1860 Heritage Centre in Johannesburg. (Photograph supplied by 1860 Heritage Centre)Sham and other comrades in the legal fraternity remember an activist lawyer who always had time for the marginalised, even if they had no money for legal fees. One who groomed article clerks as another way of “giving back to the community” and who, having learned at an early age from his father to not brook any nonsense from white people, always stood up to racist magistrates or judges.

It was because of activists like David that the 1980s so quickly gave way to the hope of the 1990s. Following Mandela’s release in 1990, David represented the NIC at the Congress for a Democratic South Africa in 1991, serving on the task team that investigated the future of the former Bantustan “states”. After this, he rejected offers of political appointments and places in Parliament to return to grassroots work among his community.

Remarking that David died on the day that Fidel Castro would have turned 94, Tsenoli said that theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht must have had the activist attorney in mind when he observed: “There are men that fight one day and are good, others fight one year and they’re better, and there are those who fight many years and are very good, but there are the ones who fight their whole lives and those are the indispensable ones.”

This article was first published by New Frame.