Take your pick: Fresh Harvest farm in Greenfield, California, is one of the largest employers of foreigners working on temporary agricultural worker – or H-2A – visas in the US. Photo: Brent Stirton/Getty Images

The modern empire of the United States was built on the backs of those who toiled on its land. Some arrived willingly, planting their flag on the New World; many were forcibly dragged by ship and chain. They built a country that can never escape its history. In that sense it’s not unlike South Africa, where the land question will probably never cease to hover over public life, politics and culture.

Now, the two narratives are intersecting in an interesting way.

Last month, The New York Times carried a story about a lawsuit filed in the Mississippi federal court in September. Six African American seasonal farm workers allege that their workplace favoured white foreign workers over locals. They say they were asked to train the new arrivals, only to see them jump ahead on the payscale, earning $11.83 an hour compared with their $7.25 — all the while having to regularly suffer racial slurs by their employers, including the flippant use of the n-word.

The foreign workers in question are South Africans. They arrived on the agricultural guest worker programme, the H-2A programme.

In theory it is a sensible piece of legislation. Conceived to address labour shortages, the scheme issues temporary visas to workers from select countries. Having been placed on a farm by one of a number of agencies the emphasis is on the employer to foot the costs for travel and accommodation. (It is notable employers are required to fork out about $2 000 for a round trip from Johannesburg, compared with a $300 bus ride from Mexico.) The regulations are many and nuanced but, in essence, employers must be able to prove that they tried and failed to employ American workers.

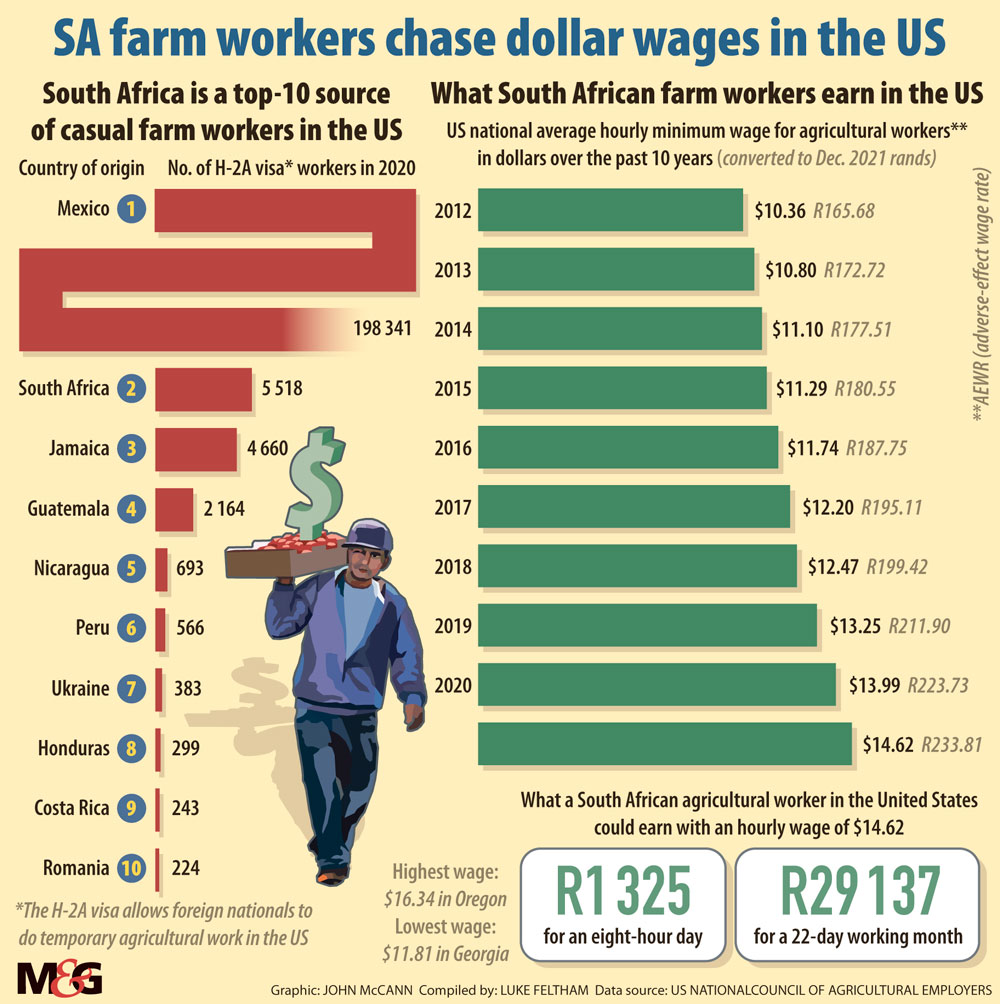

Most farm workers come from neighbouring Mexico, who constituted more than 90% of visa holders last year. In second place is South Africa, which contributed 5 518 labourers last year, according to the US department of state’s data. The importance of that contribution is highlighted by the fact that President Joe Biden acted swiftly to grant an exemption to H-2A holders after casting a blanket Covid-19 travel ban over South Africa in January.

SA farmworkers complaint by Mail and Guardian on Scribd

Again, in theory, it is a perfect match. Many young South Africans have grown up on farms and have know-how in all manner of machinery — from combine harvesters and tractors to ploughs and planters — as well as agricultural techniques. Thanks to the weak currency exchange rate, taking their trade to earn an hourly dollar wage is a highly lucrative venture. American farm owners benefit from a steady stream of semi-skilled, experienced labour.

The dynamics the H-2A creates in practice have drawn criticism from legal and human interest sectors. Before the Mississippi case, activists have long taken aim at a policy that is easily bent.

“It lends itself to abuses and exploitation,” says Amal Bouhabib, an attorney at the Southern Migrant Legal Services, who is co-counselling on the Mississippi case. “I certainly think there are good US employers and good employees and they get along well.

“But I do think there’s a lot of room for exploitation. The problem is because H-2A workers are mostly dependent on their employer for many things — their job, their housing, and their wellbeing, it can be very intimidating to stand up for themselves.”

The sentiment is echoed by the Farmworker Justice non-governmental organisation. In its No Way to Treat a Guest report report it finds: “Violations of the rights of US workers and guest workers by H-2A programme employers are rampant and systemic. The US department of labour, which has primary responsibility for administering the H-2A programme, frequently approves illegal job terms in the H-2A workers’ contracts. US workers who apply for H-2A jobs are rejected or forced to quit. Employees at H-2A employers routinely experience wage theft and other unlawful practices.”

Although Mexicans are usually the focal point of the conversation, South Africans under the programme have offered cases that may well serve as legal precedent.

‘Backwards country’

In 2019, five South Africans brought a lawsuit against their employers of the previous harvest, the Hood Brothers Farm. Their main contention was that they were yet to receive the money owed to them for travel. US labour law says that if such costs are not reimbursed upfront then they must be done so within the first week of employment.

Hood Brothers Complaint by Mail and Guardian on Scribd

According to the complaint, the two Hood Farm brothers held the funds in limbo as a way to keep their employees under their heel. This was accompanied by regular insults, including calling them “stupid fucks” from a “backwards, fucked-up country”. When the relationship became untenable, the South African employees were chased away under threat of arrest, with one even yanked from the bath naked.

The details of the case, which has since been settled, are a microcosm of many of the problems with the H-2A programme.

“He kept saying that he would give [the money] back to them when they proved they were loyal and things like that,” says Bouhabib. “And then was very verbally abusive and also emotionally abusive.

“Which, in the US, can support a claim for forced labour, which is when someone employs tactics to make someone continue working for them. In the past that used to be slavery where you chained someone. Nowadays in the US, it can be emotional or financial threats, or immigration threats. He often threatened to send them home and that they wouldn’t be allowed back into the US.”

No employers have this power but to a temporary immigrant it feels like a very real threat. Or as a South African working in northeast Arkansas in 2018 found out, it might as well be.

In his lawsuit he alleges that after he told his workplace, Gairhan Farms, that he would like to take another job, they threatened to have him arrested. After he continued to proceed with his lawful transfer of his employment, his bosses contacted the department of homeland security and reported that he had absconded. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials arrived on the same day to arrest him and he spent the next month in detention.

Released on bail, an immigration judge later ruled that his immigration status was lawful. He is now suing Gairhan Farms and Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Many agree that one of the problems is the H-2A is an exceptionally complex piece of law. The Immigration and Nationality Act, in which it is housed, is a 500-page document. The nuances often escape potential employers, wilfully or not.

Promised land

Manuel Fick, the founder of USA Farm Labor, an agency running for 19 years and probably responsible for bringing the most South Africans to the US on an H-2A visa (about 1 600 a year), insists he conducts vigorous training with the farms he works with to decrease the likelihood of the relationship falling foul.

“I have nearly 700 clients and maybe one a year, something could happen,” he says. “Our number is low because we really took a lot of effort to make sure our clients know the rules. We spent thousands on legal costs to get lawyers to advise us and we wrote a manual for all our clients. We made our contracts … [so] that if they read it and they sign it they get a lesson in H-2A.

Labour needed: A farm worker ploughs a field in Holtville, California. More than 90% of agricultural workers on H-2A visas in the US come from Mexico, with South Africa in second place. Last year 5 518 South Africans were employed to work on farms in the US. Photo: John Moore/Getty Images/AFP

Labour needed: A farm worker ploughs a field in Holtville, California. More than 90% of agricultural workers on H-2A visas in the US come from Mexico, with South Africa in second place. Last year 5 518 South Africans were employed to work on farms in the US. Photo: John Moore/Getty Images/AFP

“When a person signs up I force the client, in a nice way, to listen to a 40-minute presentation on laws, regulations, procedures of the H-2A programme. We can ensure that our clients know what’s expected of them from the worker’s side, the government’s side and the programme’s side,” Fick adds.

It is this area of support in which South Africans have a benefit not enjoyed by their counterparts. In a sentiment shared by everyone interviewed for this article, workers from South Africa enjoy an infrastructure far superior to other countries in terms of more professional agencies and networks they can fall back on, such as forums and Facebook groups.

The above legal cases notwithstanding, the H-2A programme is perceived as a golden opportunity by South Africans. Since 2011, the number of yearly participants has shot up by more than 400%.

Anzél Mans is one such beneficiary. This year she joined her husband on a farm in Iowa after he had spent the last six years travelling to the US to work. Apart from his maiden year — in which he recounted being mistreated by a farmer and his son — the H-2A programme has been a favourable experience.

Asked if other nightmare stories have filtered through to them, she says she’s aware of them but is just as wary of her countrymen that might give South Africans a bad name.

“I would say it goes both ways,” she says. “The [South African] workers that our farmer had last year messed up badly. The one just couldn’t keep up with the work. Another younger guy messed up some of the equipment because he wouldn’t listen to the farmer.

“There’s another guy that was here for a week last year because he had a big mouth and made sexual comments towards another woman. The farmer said there’s no way he’s staying. Then there are other guys that did well and the farmer said they’re more than welcome to come back. So it’s going both ways on this side. South Africans mess up, farmers mess up. If you get a good farmer and a good worker it just works out perfectly.”

Which brings us back to the Mississippi case currently before a federal court. Despite the subject of the suit being the farm owner, the origin and race of the guestworkers will probably find a prominent place in the narrative. As The New York Times describes it, South Africa is a “country with its own history of racial injustice”. Inextricably linked to that injustice is a legacy of maltreatment on the nation’s bountiful farmland. A legacy that has never been entirely eradicated.

A question that is far harder to answer is, to what extent does this case represent a sentiment shared by other American workers? Bouhabib said this is the first H-2A case she knows of in which a complaint has been registered against white workers taking black workers’ jobs. Usually, and unsurprisingly given the proportion, the grievances fall against Mexicans and the perception that they have taken away work from both white and black Americans.

Ultimately, the onus is on employers to follow the law.

“It’s complicated. We see a lot of exploitation of the foreign workers and then on the other side we can see that foreign workers are being played against domestic workers,” Bouhabib says. “And it’s all about what’s going to benefit the employer. I think it’s both … I think there’s a sense of everyone being exploited in some sense.”

Although that might be true, there is no question that the H-2A uptake is rapidly expanding: 257 667 visitors arrived in 2019 compared with 77 246 in 2011.