Violence: #SayHer1019 by Kilmany-Jo Liversage emphasises sorry by Penny Siopis depicts victims’ feeling of shame that often accompanies abuse.

For many marginalised people, the very act of existing is political. Living in a society that is patriarchal, xenophobic, ableist and homophobic, people are often faced with rhetoric that feels like an attack on them.

Political unrest and publicised cases of gender-based violence (GBV) and assault have led to politically charged art that has the power to create passionate, action-orientated images that influence, empower and spark change.

The 16 Days of Activism against GBV is an annual campaign that runs from 25 November —the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women — to Human Rights Day on 10 December.

More than one in three women experience violence during their lifetime, says the United Nations.

Art activism that speaks to gender violence and femicide is rarely a binary depiction of an experience, but rather an intersection of multiple experiences at the same time.

An intersectional view of a person’s experiences changes, according to Kimberlé Crenshaw, author of Demarginalising the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.

Art activism can be an intersectional depiction of gender violence and the artist’s native language, nationality, age, immigration status, or family duties that help transform social attitudes. Over an artist’s lifetime, their identity may change through one or more avenues of their identity as they may come out as queer or gender-nonconforming, or embrace their identity as mixed race, or alter their economic status.

Today, artistic activism can be found everywhere — in the streets (its playground of choice), gallery walls, museums, posters, Instagram, and glossy art magazines. Art activism at the intersection of gender narratives and understanding one’s own identity is a step towards understanding art activism that is centred on gender violence.

Zanele Muholi: ‘Bona, Charlottesville’ (2015)

The work of Zanele Muholi is at an intersection of the reality of gender violence and black queer communities. Muholi’s participants in their art portray the right to exist as a black, queer body with dignity, power, and agency over their own existence in the work, a true visual activist.

Muholi describes their work as art activism, “an artistic approach to hate crimes” against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer plus people, Muholi told Tate museum. They also say their pictures are political because they use a monochromatic, yet bold contrast between participant and background, giving those in queer communities encouragement to “be brave enough to occupy spaces, brave enough to create without fear of being vilified … take on that visual text, those visual narratives,” says Muholi.

Women’s wounds: Disposition of Old Ideologies by Diane Victor, Bona, Charlottesville by Zanele Muholi.

Women’s wounds: Disposition of Old Ideologies by Diane Victor, Bona, Charlottesville by Zanele Muholi.

Etinosa Yvonne: ‘Unheard Voices from Nigeria’ (2020)

Nigerian-born artist Etinosa Yvonne’s photography as activism highlights the culture in her country where “women aren’t perceived as human beings, but as things that can be owned and treated however the so-called owners please”, she tells Global Citizen.

Yvonne’s Unheard Voices from Nigeria amplifies the stories of women perceived as objects by male figures in their lives by pairing a double-exposed portrait of the subject with a written letter telling their experience of gender violence. One letter tells a story of a physical violence with an on-and-off divorce because of pregnancies, forced marriages among cousins, and silencing victims of sexual violence.

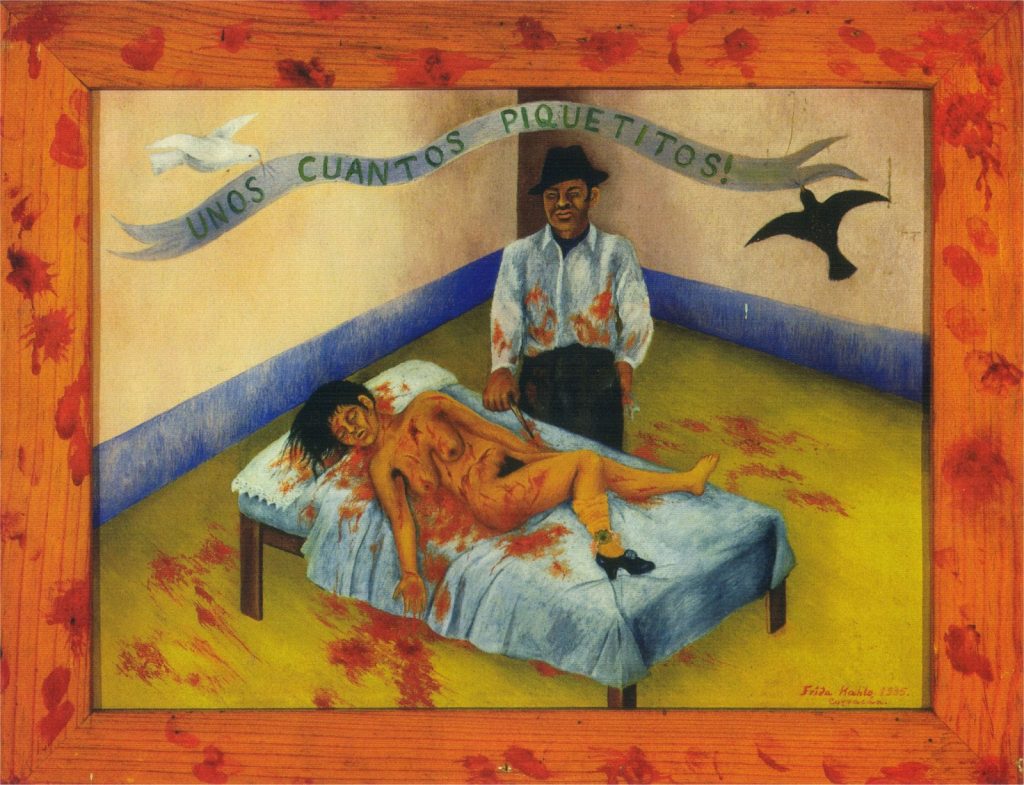

Frida Kahlo: ‘Few Little Pricks’ (1935)

The Mexican-born artist Frida Kahlo is known for her feminist paintings that speak to a woman’s emotions and positionality.

Her painting, Few Little Pricks, depicts a naked, blood-covered body at the hands of a male-presenting figure. It was inspired by a husband who accused his wife of adultery and stabbed her.

Few Little Pricks by Frida Kahlo reflects the violence of intimate partners.

Few Little Pricks by Frida Kahlo reflects the violence of intimate partners.

The painting’s banner reads, “Unos Quantos Piquetitos [a few little nips/pricks]’’, which is what the guilty husband called the stab wounds on his wife’s body. The painting speaks to the reality of many women who fear for their lives at the hands of their partners. Almost 22% of assaults are committed by a friend or acquaintance and 15% by a spouse or partner, according to Statistics South Africa.

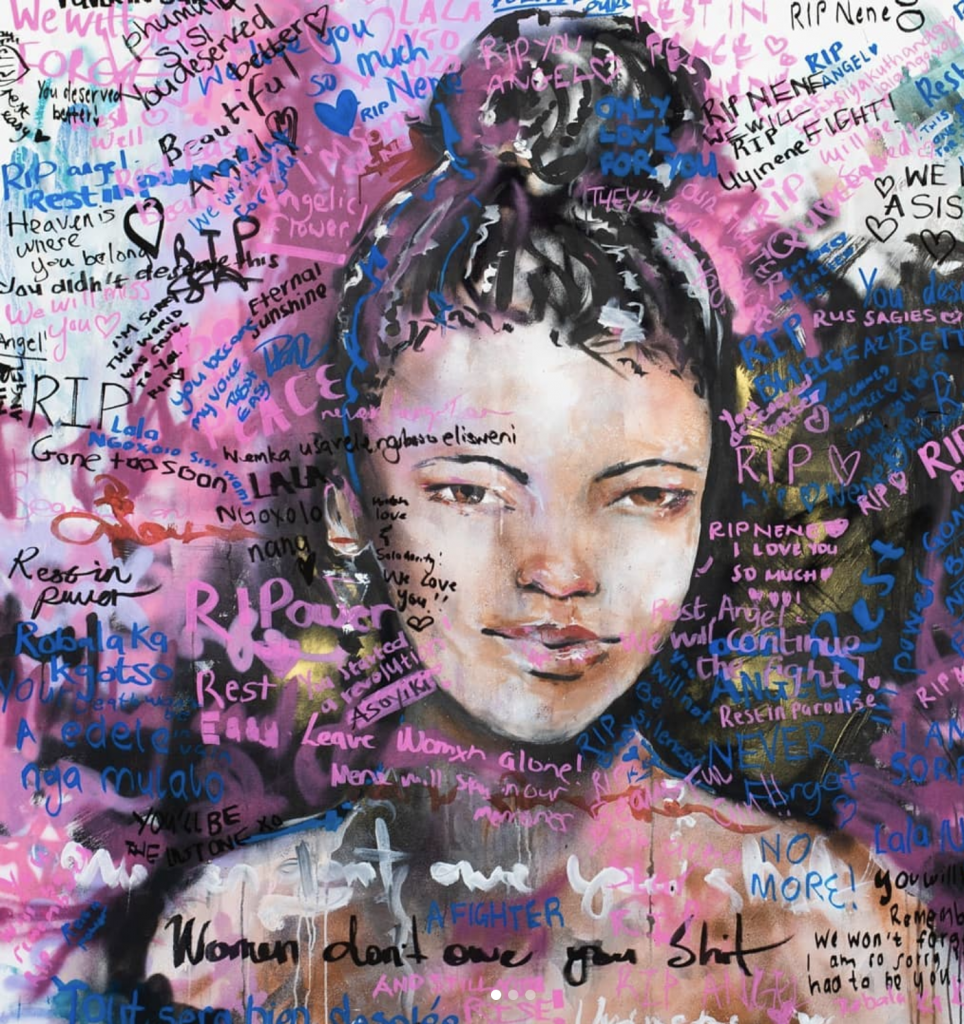

Ana Kuni: ‘Rest in Power’ (2019)

The rape and murder of University of Cape Town student Uyinene Mrwetyana in 2019 by a post office teller sparked some of the loudest protests against South Africa’s gender violence and femicide crisis. As of November 2022, there have been 11 000 rapes reported in the last 90 days, according to the South African Police Service crime statistics.

Ana Kuni’s work typically depicts warrior-like women; symbols of strength to stand up against gender violence.

Her artwork depicting Mrwetyana contains words written by her fellow students.

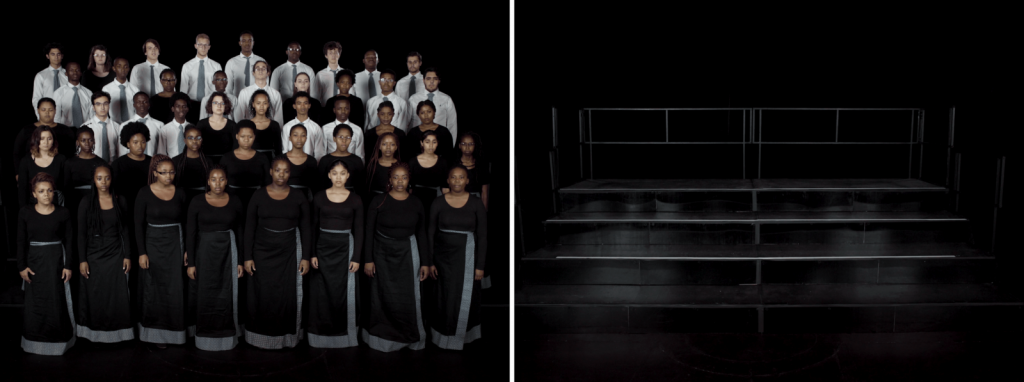

Gabrielle Goliath: ‘Chorus’ (2020)

Gabrielle Goliath is a Kimberley-born multimedia artist whose work speaks to situations of gendered and sexualised violence and was also triggered by the murder of Mrwetyana and subsequently the “Am I Next?” movement, where South African women asked whether they were the next to be another victim to the gender violence crisis.

Goliath’s work, Chorus, is a communal (and intersectional) recognition of black feminine life. Chorus is a performance by the UCT choir, who sound a “lament for Uyinene Mrwetyana — not as a song, but the internally resonance of a hum, collectively sustained as a mutual offering of breath”, says Goliath. Chorus is paired with a commemorative scroll of 735 names of those people who lost their lives as a result of gender violence in South Africa.

Diane Victor: ‘Disposition of Old Ideologies’ (2020)

Diane Victor, whose medium is drawing, makes art that is a raw depiction of the gender violence crisis, laced with dark humour.

Victor’s art as activism highlights not just the existence of the gender violence crisis, but the harmful culture around sexual violence against women, specifically that which trivialises it; witch-hunt-like acts of violence and “women who have been made to bear responsibility for the abuse inflicted on them”, according to the Goodman Gallery.

The 2020 drawing Disposition of Old Ideologies references Christian themes, urban waste sites and symbols of power and resistance against Western powers that cast marginalised groups into outcasts.

The weak body of an old white man, carried by two powerful women, is depicted in a waste site where his body is either reclaimed or disposed of.

The piece is a form of activism against narratives designed by Western white males who are being challenged by contemporary status to embolden typically assaulted bodies to assume positions of power.

Carin Bester: ‘She Had a Name 365’ (2021)

Performance artist Carin Bester best highlights the need for more than 16 days of activism in her artistic videos that bring to light the ongoing and repetitive reality of femicide in South Africa.

Bester’s performance in She Had a Name 365 has her saying “She had a name” with the next consecutive number every 190 minutes on social media. Every video aligns with a woman being murdered in South Africa. Bester’s activism in performance comes in a weekly video of the combined clips, posted with details of organisations, shelters and campaigns fighting against gender violence.

The performance began on 1 April 2021 at midnight (aligned with the beginning of the South African statistical year) and runs for a year-long performance cycle. Bester’s crime statistics from April 2015 to March 2020 shows that an average of almost eight women were murdered every day, for five years.

Magali Trapero: ‘Breaking Free’ (2021)

Magali Traperos’ painting, Breaking Free, shows how the Mexican artist injects the human spirit and the natural world into her art, which focuses on social justice. The piece speaks to life as a collage of beauty and inner pain, intertwined with a body’s undeniable hope and moments of joy.

Breaking Free makes use of three birds symbolising hopes of freedom from the reality of gender violence, and a hopeful woman, despite bearing violent wounds. The artwork was also used as a billboard to empower victims of gender violence to reach out for help from organisations. The painting is artistic activism that has a narrative of power and resilience while the reality of gender violence exists in the shadows.

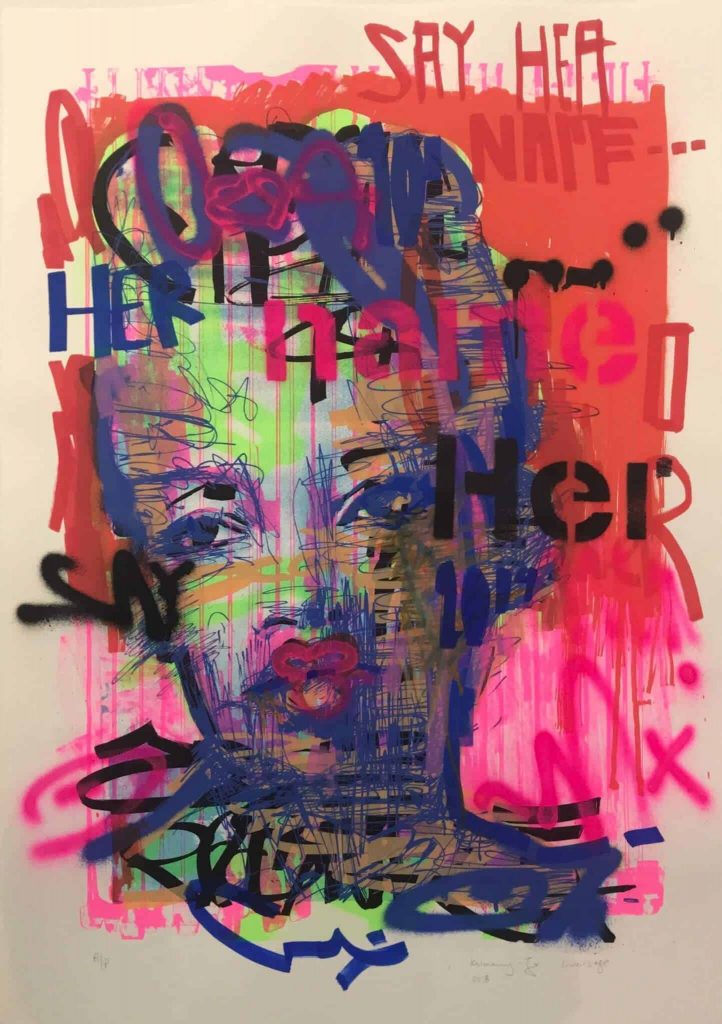

Kilmany-Jo Liversage: ‘#SAYHER1019’ (2019)

Symbols of activism do not only include clenched fists, flags, gendered symbols, peace and war. The identity of women is often lost in a world of the mythical norm; a false assumptions of a white, male standard, as identified by black feminist Audre Lorde.

#SAYHER1019 by Kilmany-Jo Liversage shows the important renegade message by depicting the female subject whose face is blue, scratched, distorted and destroyed.

The vibrant colours give deserving life to the face of not just the single women in the picture, but all those who are victims to gender violence.

The repetition of “Say her” signifies the urgency of the need to recall a body’s name, identity, and significance in the world.

Penny Siopis: ‘Shame. Sorry’ (2004)

Shame is both a public phenomenon and psychological condition. Penny Siopis, known for her swooping watercolour paintings in vibrant colours that depict both the abstract world and realities through symbolic gestures, speaks to the feelings of shame imposed by the world on those with experiences of gender violence in Sorry, a part of her Shame series.

Sorry depicts a young female-presenting body at the mercy of a raised hand, but she is the one saying “I’m sorry”. The shame culture that surrounds gender violence is multi-dimensional. From within, the psychological nakedness and vulnerability that comes from loss of dignity. Shame from the outside is more empathetic and colloquial — South Africans often say “shame” to acknowledge pain.

The gender-based violence hotline is 0800 428 428.

[/membership]