Ukrainian forensic experts describe the bodies of dead Russian soldiers, who died in settlements north of Kharkiv. ( (Photo by Ivan Chernichkin/Zaborona/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)

A new identification programme initiated by the humanitarian organisation International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) hopes to enable military institutions to identify combatants killed in conflict by using basic DNA profiling before they are deployed.

Many soldiers are unaccounted for on battlefields and there is only a limited chance of identifying those who are found and returning their remains to their families. Science can provide a solution, according to Stephen Fonseca, manager of the ICRC’s new African Centre for Medicolegal Services (ACMS)

“Failure to develop military identifications programmes contributes significantly to dead combatants being misidentified or not identified at all,” said Fonseca.

Using medico-legal assessments and observations, he said the ACMS realised “there is no military programme or guidelines, especially in Africa, that explains how soldiers need to be searched for, recovered, examined, stored and ultimately identified, based on what was collected before going out on battle”.

Simply put, there are no preliminary steps taken to identify soldiers before they are sent to conflict areas.

Citing historic inventories of the missing, Fonseca said, in many cases, people were labelled as missing because there was no forensic structure in place to compare corpses with existing data.

This is why the ACMS, a satellite hub of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies’ Missing Centre, proposed the Military Identification Programme forensic project.

Under the Geneva Convention, of which South Africa is a signatory, countries are obligated to report the dead of both sides during wars or other conflicts.

But, Fonseca said, to make reporting the dead a standard practice, more than the law was needed. “You need people to understand why it is important to preserve the dead.”

From a general perspective on missing person situations — be that person missing because of migration, war or disaster — “if there isn’t a structured programme bringing back the bodies of loved ones, or at least informing them about their loved one … the whole social structure falls apart for that family”.

Still in its infancy, the programme aims to collaborate with non-state and state military groups to establish DNA profiling of combatants before they are sent to battle.

Fonseca said forensic science had advanced to the extent that it was rare to come across a case where identification was impossible.

“You give me something human — material or elements — and I’m going to find a way to develop a DNA profile.” But, he added, “It is useless if you don’t have something to compare it with.”

That is why a structured DNA profiling programme that collects DNA samples of combatants is crucial.

Soldiers cannot be forced to give a DNA sample but doing so could reassure troops that if they die in combat, their remains can be returned to their families.

Private security companies already make use of DNA profiling for their members.

Leonora Theart, chief executive of Unistel Medical Laboratories in Cape Town, said gathering DNA samples was a relatively straightforward process.

The laboratory, has also compiled DNA profiles for private security companies in the past. Theart said the estimated cost of doing such a profile is R1 500.

Fonseca places the affordability of the military identification programme in context by comparing pre-conflict DNA profiling with post-conflict identification processes.

Exhumations, forensic specialists and DNA profiling for bones are “enormously expensive”, he said, when compared with profiling using a person’s nails and blood.

Criminologist in a protective suit against the barricade tape holds a physical evidence in a plastic bag at the crime scene in abandoned warehouse

Criminologist in a protective suit against the barricade tape holds a physical evidence in a plastic bag at the crime scene in abandoned warehouse

Reuniting the dead with the living

The effectiveness of forensic identification lies in its many successful projects where DNA samples were not always available but where family members came forward to report their loved ones were missing.

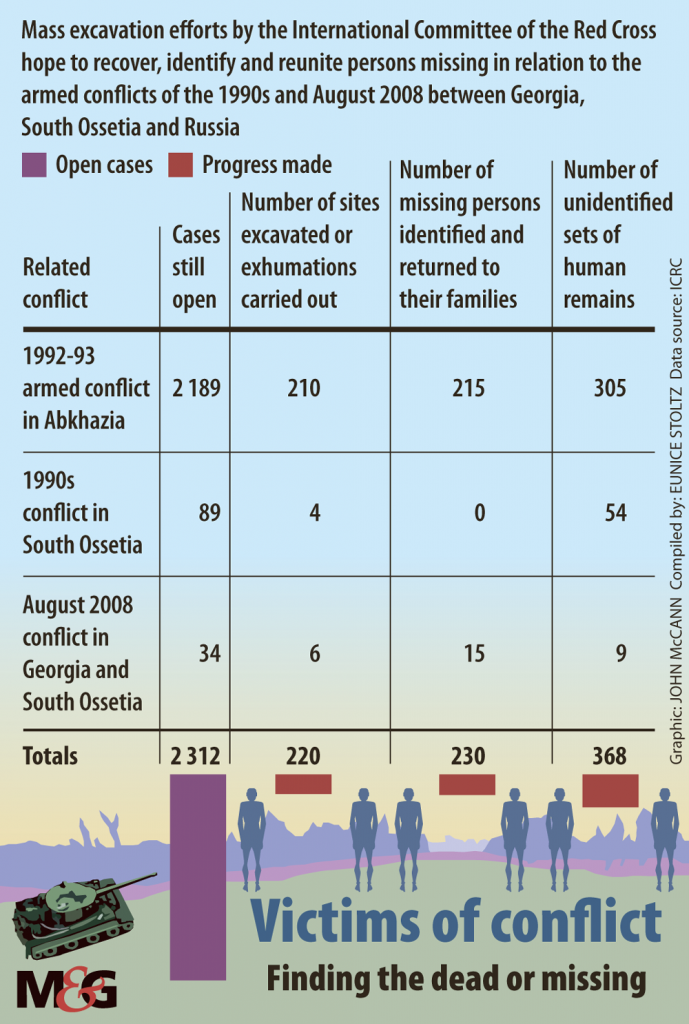

The ICRC in Georgia, formerly part of the Soviet Union, provided the M&G with recent statistics of an ongoing project aiming to clarify the fate and whereabouts of people missing in relation to the armed conflicts of the 1990s and in August 2008.

Of the project, Fonseca said: “Over 2 300 people are still unaccounted for. The families have lived long years of anguish and uncertainty … not knowing what happened to their loved ones. Not being able to give them a dignified burial, or a place to mourn, generates an intolerable burden.”

Over the past decade, more than 220 sites in Georgia have been excavated and 230 bodies identified and returned to their families.

Closer to home, Fonseca spoke of the success of a small project in 2017 relating to 60 Zimbabwean migrants. Of the 60 missing people, remains were returned to 14 families through forensic identification.

“This programme is needed,” said Fonseca. “Having the forensic information will allow a family who comes forward saying they lost a loved one to have multiple avenues to identify that person, today or in 20 years time.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Implementation and affordability

He acknowledged the difficulties in implementing the programme at military institutions. “[The programme] is not complicated but, if you never had a forensic structure, it takes some expertise to mentor and develop.”

The ACMS provides services that include rolling out the programme and giving practical and implementable guidelines to military institutions, added Fonseca.

It can start with basic information, such as a DNA card, “something really simple and inexpensive”.

He stressed that this was not a solo project and that collaboration with the military group was essential.

It was hoped that the project would “bring the humanity back into war”.

“We have to give a lot of importance to the way the dead are managed. Families have the right to have their loved ones returned.”

Fonseca said the programme could sensitise soldiers and military institutions towards the dead — their own and those of their opponents. He added that each institution would receive assistance based on its unique context because some military groups would not necessarily want to be identified.

The unaccounted

He recounted a recent project on a modern battlefield, the location of which cannot be disclosed.

Scattered across the battlefield, 6 000 individual body parts were recovered by forensic specialists from the ICRC over five days. The country’s governor had asked the ICRC to help excavate the human remains because part of the battleground was earmarked for farming.

The bodies had been scavenged by wild animals and were beyond recognition.

The rest of the battleground will carry, for now, the remaining missing and dead, the total number still unknown.

“We don’t know how many people are missing, we do not know how many people are dead. We don’t know the numbers,” Fonseca said, referring to battlegrounds around the world.

“These numbers go up into tens of thousands in other conflicts, and let’s be honest, they are not going to be identified. The numbers are just too great.”

Authorities become too overwhelmed to identify all the dead and they say it is not viable, said Fonseca, “when in fact it should be viable”

[/membership]