Burpathon: Cattle that graze emit more methane than feedlot-fed animals, and tend to be owned by poorer farmers. But the scale of feedlot production makes these the emissions winner. Photo: Universal Images Group/Getty Images

South Africa’s beef industry plays a crucial role in the country’s economy, food security and employment. But its environmental effects and inequalities in the sector have made a shift towards a just transition necessary.

This is according to a new guidance memo and policy brief produced by the Institute for Economic Justice.

Agriculture is responsible for about 11% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, with livestock accounting for 70% of these emissions. Beef cattle were responsible for about 64.5% of direct livestock emissions in 2020, amounting to about 6.7% of South Africa’s total emissions.

The sector’s ecological footprint is further exacerbated by the intensive use of land, feed and water, “raising concerns about its sustainability”, the memo said.

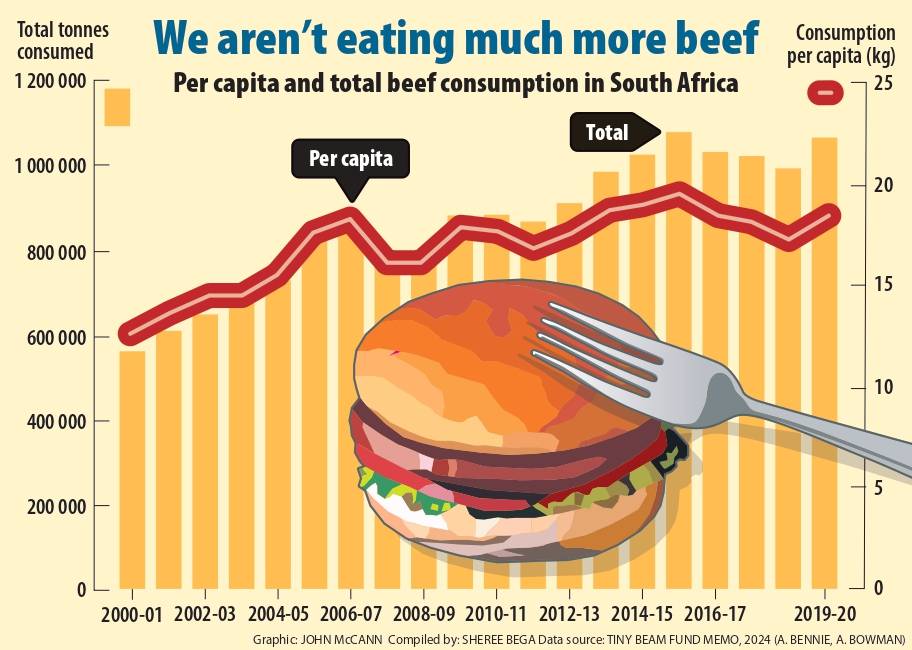

Per capita of beef available for consumption in the country is about 18kg a year, close to high-income countries. But high inequality is inherent in this consumption: the richest 10% of the population spend more than 14 times as much a year on beef as the poorest 10%.

“We chose the beef angle because, as a food type in the food system, it had the highest environmental footprint in terms of climate emissions, landscape impacts and in terms of water and air impacts and also because of its prominence in global discussions around the relationship between the food system and climate change,” said Andrew Bennie, a researcher in climate policy and food systems at the institute.

A further driver was the strategy released by the red meat industry in 2022 to grow the industry by targeting exports. About 95% of beef produced in the country is consumed domestically and it is the second-most important animal protein after chicken.

Only 5% of beef is exported and the strategy seeks to increase this to 20%. Key to the strategy is to intensify the integration of black emerging and smallholder farmers into commercial beef value chains.

“Industry bodies have begun linking this strategy to a just transition, which is associated with growth in jobs and livelihoods as a result of industry growth, together with addressing environmental concerns through technology,” the memo said.

But global concerns about the environmental effects of beef production, and the need to address South Africa’s unemployment and poverty crisis, raise questions about increasing beef production in a just way for the country, according to the memo.

South Africa was the 14th-largest beef producer in the world in 2022, with output of just over one million tonnes, and estimates show that there are between 12 000 and 30 000 formal cattle farmers and in the informal sector about three million households own cattle.

Cattle farming connects to other agro-industrial activities in the value chain, such as feed production and meat processing. Beef production is a major consumer of maize and soya, said the memo.

The bulk of greenhouse gas emissions from beef cattle are from enteric fermentation — a digestive process in ruminant animals — and manure management. Methane’s contribution to global warming in the shorter term is intense, the memo noted. It is 86

times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year timespan. But it is shorter-lived than carbon dioxide; its potency reduces to about 28 times more than carbon dioxide over 100 years.

Given methane’s short-term effects, lowering its emissions has become a prominent focus globally in limiting global warming, Bennie pointed out.

To keep emissions at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels requires reducing emissions from all sources by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030.

Proposals to do this in the beef sector rest on lowering people’s consumption and production of meat.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The memo said extensively grazed cattle have higher direct emissions intensity than those raised in intensive — feedlot — systems, because of “production efficiencies” in the Latter.

“The low percentage of emissions is also explained by the fact that at any one time most cattle are extensively grazing on pasture and so a small proportion are in feedlots,” the report said.

“Although 75% of beef consumed in South Africa has come from a feedlot, most of such animals are first extensively raised on pasture for six to nine months before being ‘finished’ for 110 to 120 days in a feedlot.”

Extensively grazed cattle on commercial farms produce less carbon emissions than those in communal systems, because of production efficiencies such as higher calving rates and breed selection. As such, cattle with the higher emissions intensity predominantly come from low-income households, pointing to an “equity dimension” in considering emissions.

Most cattle-owning households are poor and therefore in the bottom 50% of income earners in South Africa, who emit on average 3.5 tonnes of CO2e [carbon dioxide equivalent], compared with 27.8 tonnes of CO2e of the top 10% of income earners.

“Thus although their cattle have the highest emissions intensity, they are crucial to these households’ livelihoods, and such households are still only responsible for a marginal amount of South Africa’s emissions.

In light of concentration in commercial production, and high beef consumption by higher income groups, the emissions associated with both are highly concentrated.”

The researchers said the question of economic inequality and inclusion of smallholders is also linked to inequality in the distribution of emissions, and “so is a climate justice question”.

“It is mostly better-off cattle farmers who have the ability to take]advantage of efforts to include black farmers in commercial beef value chains. “There are therefore major questions about the ability of existing strategies for market inclusion to result in broadscale, equitable inclusion,” the institute’s memo further read.

Emissions from beef cattle have remained relatively stable since 2000, but the growth strategy implies they could rise, without mitigation measures.

But current policy does not provide a target for emissions reductions in agriculture, with the draft sectoral emissions targets (SET) published in April planning for most emissions reductions to come from energy and industry.

The department of agriculture, land reform and rural development said its climate change sector plan and climate-smart agriculture strategic framework for agriculture, forestry and fisheries have highlighted the economic implications of adaptation and mitigation, as well as safeguarding national priorities such as food security.

“These plans and policies further highlight that climate change can have negative impacts on the economy as it affects agricultural production and will ultimately affect food security and export opportunities,” it said.

The department said it has adopted a position to prioritise a climate change sector response that focuses on increasing the ability of it to adapt. It plans to do this by enhancing the resilience of food and agricultural production systems (adaptation) and reducing the agricultural greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) while safeguarding national food security in a just transition to a low-carbon economy and society.

The department said it is working closely with other government stakeholders, including the provinces and implementing agencies, to ensure uptake of the climate information and that farmers implement tailormade adaptation and mitigation strategies on the ground.

In addition, it is developing its greenhouse gas emission reduction plan.

“These initiatives will help the country in achieving the net zero targets in line with South Africa’s low emission just transition framework and to respond to the emission sector targets as set out in the SET framework and in accordance with the Climate Change Act,” the department said.