The hole nine yards: Pothholed roads and a fallen electric pole, which took more than a month to be repaired. (Lunga Mzangwe/M&G)

The collapse of basic municipal services, like road maintenance and water and electricity provision, due to corruption, political infighting and maladministration, has left the towns of QwaQwa and Harrismith in the Free State a shadow of their former selves.

Residents of Maluti-A-Phofung municipality, a casualty of internal squabbles within the governing ANC, have lost hope of anything changing, despite the recent appointment of a new mayor and municipal manager.

Scores of businesses there have collapsed due to poor service delivery, leaving people without jobs.

The QwaQwa industrial area is riddled with water-filled potholes. More than 30 firms have shut down and abandoned their premises in all three of its zones.

The owner of one of the few that are still in operation, who asked not to be named, said the companies had closed because of poor water and electricity supply, which the municipality had failed to address for years.

“They will just switch off electricity for three months and there’s nothing you can do.

“You are then forced to rent a generator, which is paid daily, and you have to buy diesel, which is not sustainable,” the business owner told the Mail & Guardian.

“Water is a dream here. We have not had flushing toilets for years because the government neglected the area and opportunists took advantage of that.”

Despite this, the Free State Development Corporation, which owns the industrial areas, forces tenants to pay rent.

“After Covid, a lot of people decided it was not worth it anymore and shut down,” the business owner said.

In the nearby Tseki township, the roads were also badly potholed. A resident, who identified herself only as Ntabiseng, said they had last been repaired between 2002 and 2004.

Abandoned business premises, one of which appears to have burnt down, in an industrial park in Maluti-A-Phofung municipality, in QwaQwa, in the Free State

Abandoned business premises, one of which appears to have burnt down, in an industrial park in Maluti-A-Phofung municipality, in QwaQwa, in the Free State

“It’s over 20 years now and it has got to the point where we don’t care anymore,” she shrugged.

About 40km from QwaQwa lies the industrial area of Tshiame in Harrismith. Here, too, the roads are in a shocking state and at least 20 companies have packed up and left.

At an apple-processing plant, at least 1 000 community members from the Khalanyoni township were queueing for 150 temporary jobs. Many had already given up because of the length of the queue.

An employee at the firm said this was a new company in the area, which was going to hire 150 people for six months.

“It was surprising to have so many people apply for these jobs,” she told the M&G.

Resident Palesa Molefe, one of those who gave up the job queue and went home, said she had been standing in the line from 8am but it had barely moved.

“I was working before. There was a firm that made jerseys and they laid off about 300 people,” she said.

“We would go for three months without electricity and water was on and off.

“The owners told us that they could not afford to operate anymore because they were making a loss in keeping their doors open.”

Stink over neglect: Residents of Maluti-A-Phofung municipality, in the Free State, have sewage running down their streets. Photo: Lunga Mzangwe

Stink over neglect: Residents of Maluti-A-Phofung municipality, in the Free State, have sewage running down their streets. Photo: Lunga Mzangwe

A heavy stench of sewage hangs over Khalanyoni and the verges are overgrown.

“Re dula masepeng,” one resident told the M&G, which loosely translates to, “We live in shit.”

Many locals were wearing long rubber boots because they have to walk through sewage every day.

Mhlalefe Mosia, who moved into the area in 2009, said it had been neglected by the municipality even back then.

“We don’t even have hope that this will ever get fixed.

“These people are not even able to come up with a way to open up just one gravel road. How would they fix the entire sewerage [system] in the township?” Mosia asked.

“If you have a car, you can’t park it in the yard because the road is completely closed because of the sewage.

“You have to park in the yards of those who still have a road, and pay for it monthly, while you have your own yard.”

Shop owner Melita Malakwane said people had been begging the municipality since 1998 to fix the road past her house, which was so bad that she could not drive her vehicle in or out.

“We wrote a letter to the municipality asking to be assisted — but nothing,” she said.

“Now they say we don’t pay for services and that’s why they can’t fix it but, back then in 1998, we were paying for services and still nothing happened.

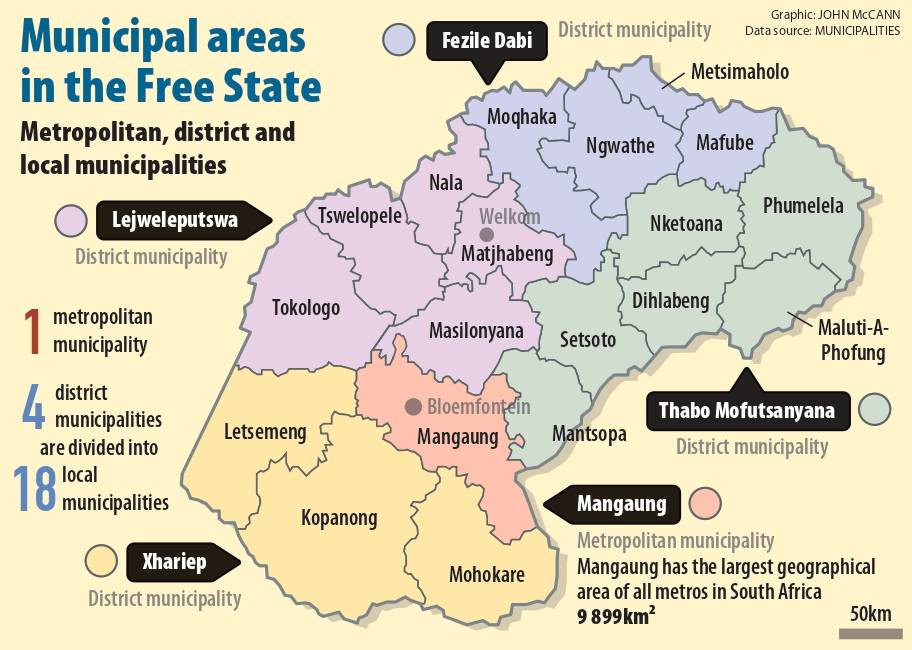

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“People stopped paying for services when they could not drive their cars in their yards.”

The situation is so bad that Malakwane is forced to hire a car to go to town and buy stock, while the bakery truck making deliveries to her shop has to park half a kilometre away from the premises.

“My business is slowly dying. It’s been three years now watching it collapse slowly. I’m just waiting for it to completely collapse.

“Who would want to walk on sewage to come and buy in a shop?

“The houses are also smelly,” she said dejectedly.

In 2018, the Free State provincial government placed Maluti-A-Phofung municipality under administration after years of extensive corruption and maladministration under the ANC, with a national intervention taking place the following year over issues including an unpaid R2.2 billion Eskom bill.

In September, the municipality and Eskom reached an eight-year agreement aimed at restoring its technical and financial sustainability, enabling it to pay for bulk electricity from the utility and continue providing it to customers as a basic service.

The agreement, which can be extended to 15 years, followed an order from the Pretoria high court concerning the municipality’s outstanding Eskom debt — which had risen to R8 billion by the end of July.

The municipality’s financial problems are partially a result of faction fighting in the ANC. This saw rival groups appointing staff on inflated salaries, with some general workers being paid R100 000 a month at one point, according to sources in the municipality.

One source related how, in some cases, general workers even had their own assistants, who were paid by the council.

“It was so bad that, for instance, a person who is hired to be an electrician, the requirement is that they should have a driver’s licence, but some of them do not have it.

“Then a driver needs to be booked for that. That driver will claim overtime,” they said.

The source also claimed that the water crisis in the municipality was “manufactured” to benefit some people financially.

“QwaQwa is full of dams and some of the dams even supply Gauteng. How is it then the people here do not have water?

“This thing is created so that those who have water trucks can get tenders to deliver water.”

Since 2018, the municipality has had four mayors, another indication of its instability.

In the 2021 local government elections, the ANC failed to obtain the 50%+1 required to govern outright, forcing it to go into a coalition with smaller parties including the African Transformation Movement and African Content Movement.

Maluti-A-Phofung mayor Malekula Melato said she had been given a chance to lead the municipality when it was ailing, unstable and had not had a municipal manager for four consecutive financial years.

“When I took over, the infrastructure was ailing — water, electricity, road infrastructure — and things were not looking that good,” she said.

“I’m now five months in the mayor position and I can tell you now that I’m very comfortable and things are shaping up.

“If you go around Maluti-A-Phofung you’ll see that there’s a lot of development happening.”

Melato said the council had been fixing potholes and roads under the expanded public works programme, using municipal workers.

The appointment of a municipal manager had helped fast-track service delivery, she added, with the electricity supply also stabilising.

“Eskom managed to assist us to maintain the electrical substations.

“We have a DAA [distribution agency agreement] with Eskom that we have signed in which they are assisting us in terms of electrical issues and maintaining our electrical bill,” the mayor said.

The council had managed to extend the water supply to Makgolokweng in Harrismith, which had not had the essential resource for 25 years, Melato added.

So-called “water mafias”, who vandalise infrastructure in order to create an opportunity for themselves to deliver water at a price — especially to guesthouses in the area — remain a problem.

“It’s true we have challenges in terms of our ailing infrastructure which has been vandalised because of the water mafia.

“But over and above there’s an issue of climate change and our Fika-Patso Dam is very low because of the climate change,” Melato said.

“The other issue affecting Fika-Patso is the water leaks because of the vandalisation. This has affected us adversely.

“We do communicate with the community to say this is the situation we find ourselves in.”

The municipality is pursuing an open communication policy with residents so they are fully aware of its efforts, she said.

“The relationship with the community and the employees of the municipality and the council is fundamental. When I arrived, staff morale was low. We have made our employees understand the importance of the job they are doing.”

Melato acknowledged unemployment was rife in the municipality, saying the recent closure of the Clover plant, and other companies pulling out, had made it worse.

The council’s focus was to start fixing infrastructure to ensure uninterrupted supply of water, electricity and proper roads to attract investors. The Harrismith industrial area had been prioritised for intervention this year, she said.

“If we get this right, it will automatically activate these social issues which relate to job opportunities. In Harrismith we have a special economic zone which is not doing so well, it’s a huge project which can create a lot of job opportunities.”

Melato also urged residents to pay for services — including water and electricity — to help the municipality deliver on its mandate.

“It is true we are on the wrong side as the municipality but communities also have a responsibility. The situation is not dire like before. You go everywhere in QwaQwa, there’s water and the only time there’s no water, you must know that we have closed it to ration for hours in between to manage the level of the dam.”

African Content Movement leader Hlaudi Motsoeneng, whose party has two council seats, said residents were their “own worst enemies” because they continued to vote for the ANC in the municipality.

“The answer to all these issues is for which party you are voting. How do you vote for a party that messed up the municipality and you still dream that they will put service delivery? It won’t happen,” he said.

Motsoeneng said placing the municipality under administration again would not help and that the municipal manager needed to be left to do his work without political interference.

“We need the municipal manager to lead and be given the freedom to run the municipality and politicians should not get involved,” he said.

Free State economic development and tourism MEC Toto Makume, under whose department the Free State Development Corporation falls, said it was not aware of a mass exodus of companies but many had raised concerns about water and electricity supply interruptions.

He was negotiating with some companies to persuade them to stay and had provided some businesses in Tshiame with generators.

Makume said he had been in the area over the festive season and there had been no water and electricity supply interruptions in most parts of Maluti-A-Phofung and Dihlabeng, which was “an indication that there is work in progress, thanks to the leadership of Maluti-A-Phofung”.