Without biocontrol, Hartbeespoort Dam could be 70% covered in superweed

The “super invasive” aquatic weed, water hyacinth, is covering nearly 40% of the polluted Hartbeespoort Dam in the North West. But it would be far worse if its natural foes — the tiny water hyacinth hoppers — were absent.

“The fact that Hartbeespoort Dam isn’t 70% covered right now is incredible,” said research scientist Julie Coetzee, the deputy director of the Centre for Biological Control (CBC) at Rhodes University. “And that’s because of these insects keeping it at bay.”

Biological control relies on the safe use of natural enemies of invasive species to feed on them and reduce their populations. For Harteespoort Dam, this arsenal is the Megamelus scutellaris hoppers, which feed and lay their eggs only on water hyacinth.

The biological control programme the CBC initiated on Hartbeespoort Dam in 2019 has involved the release of more than a million of these sap-sucking insects to decimate the water hyacinth, which thrives in polluted, nutrient-rich water, such as that of Hartbeespoort Dam.

As South Africa’s most problematic aquatic invasive plant, water hyacinth forms impenetrable mats that destroy aquatic biodiversity and prevent boating and water sport activities. The weed has plagued the dam since the 1960s, flowering and producing prolific numbers of seeds that can remain viable for about 25 years.

The current state of the dam is not unexpected, said Coetzee. “It’s the fifth year in a row that we’re having this pattern. The population [of water hyacinth] crashes in the middle of summer from the biocontrol agents and then it stays at a very low level over winter. Come spring time, it starts to emerge.”

Water hyacinth can double its biomass under ideal conditions, which include warm summer temperatures and high nutrient waters. The dam is heavily contaminated by sewage and agricultural and industrial runoff, which flows into the rivers feeding it.

Throughout 2019, the CBC frequently released hundreds of thousands of the bugs, and at the start of January 2020, the mat collapsed. By March 2020, less than 5% remained and it plunged to below 2% over winter.

The plants returned in spring in October 2020, because of the extensive seed bank lying dormant in the sediment. The CBC continued with its inundative release campaign over the rest of 2020, and in early summer of 2021, the mat collapsed once again. But the same pattern occurred in the following years, including this past season in September 2024.

The CBC relied on funding for this biocontrol programme from the department of forestry, fisheries and the environment, but this ceased in 2022. Yet the centre continued to mass rear and release the bugs by establishing rearing stations run by local residents.

There are now 10 stations which are self-funded and maintained. Since August, they have released 100 000 bugs a month.

“They’ve been amazing,” Coetzee enthused. “We have a Whatsapp group going and we all communicate with each other.”

The main aim of the rearing programme is to release as many bugs as possible as soon as the new plants germinate early in the spring.

“This January, we are experiencing the same phenomenon we have seen over the past five years,” she said. “The plants germinated in spring, the bugs were released, December rains increased the nutrient runoff into the dam, giving the plants more food and so they exploded.”

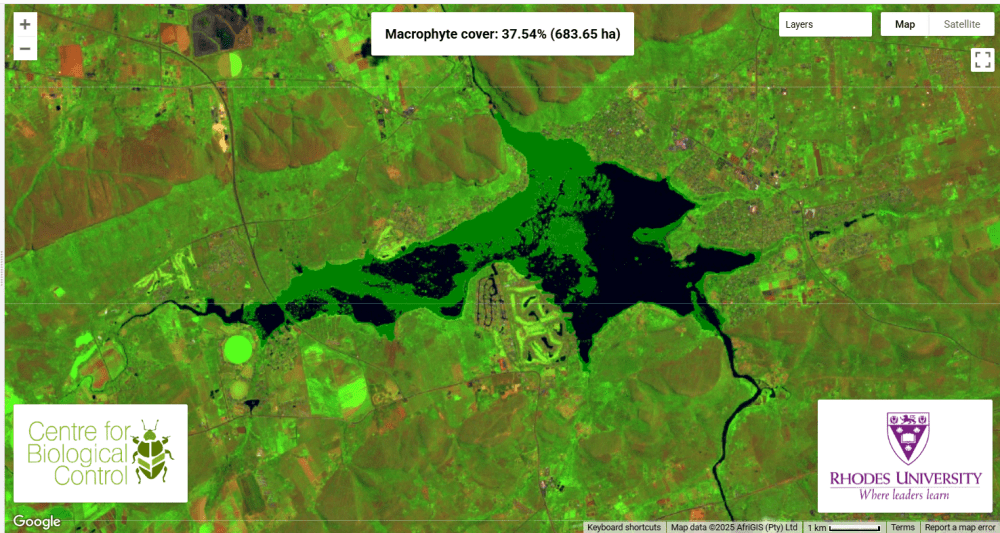

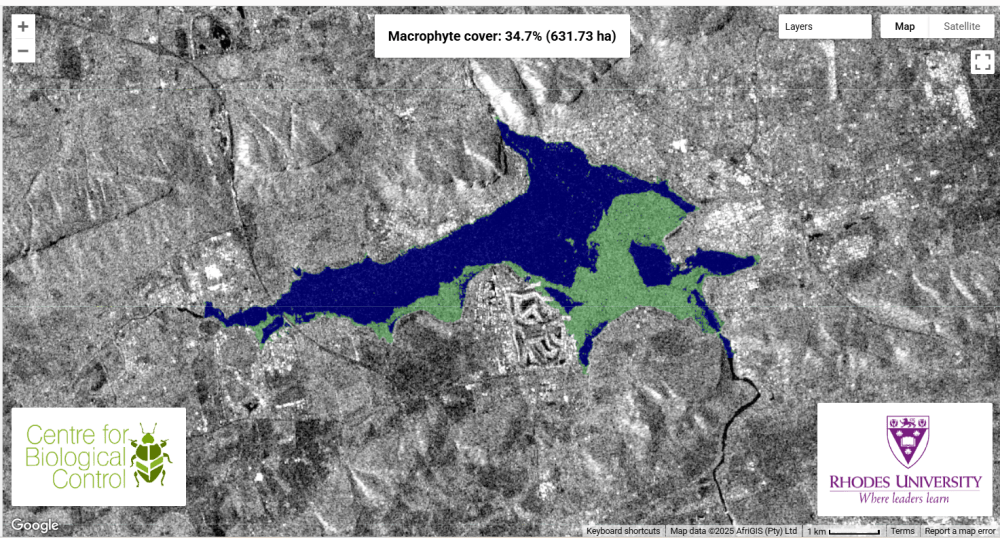

The first satellite image is from 25 January ad the second image is the radar image from 24 January, showing how the mat moves within a day.

The first satellite image is from 25 January ad the second image is the radar image from 24 January, showing how the mat moves within a day.

But the bugs are catching up, as they have each year. “Very importantly, the biocontrol damage prevents the plants from flowering and therefore producing seeds. This means no new seeds are added to the seed bank.”

Another factor driving this season’s growth of the free-floating plant is the very low water level at the beginning of the growing season, exposing seeds that have remained dormant at depths below their germinating capability.

Coetzee said the CBC looks forward to working more closely with Magalies Water, which, in April 2023, was appointed for a 36-month period to implement a remediation plan to improve raw water quality in the Crocodile West catchment upstream, including Hartbeespoort Dam.

Its spokesperson, David Magae, said the remediation strategy and implementation is driven by a multipronged approach.

This includes cooperation with various partners such as the CBC, which in the past together with Magalies Water, have made “significant progress in managing and curbing the rapid growth of the hyacinth”.

In addition, Magalies Water is in the process of appointing a competent service provider for the biological control aspect of the project.

Magalies Water has increased the mechanical removal of water hyacinth, which are “locked” in one area of the dam. “The remaining challenge is the continuous contamination of the dam from human-caused activities upstream,” Magae said.

“The water hyacinth continues to receive nutrients and its proliferation is inevitable … Evidence available to us indicates that, unless there is significant reduction of these [pollution] activities upstream the re-growth of the plant will continue unabated.”

Coetzee said her unit didn’t release a single Megamelus from Rhodes this last season “because we have no funding. It’s all been done by the community rearing stations with our scientific guidance and continuous involvement.”

Last year, she was awarded the DSI/NRF SARChI Tier 1 Chair in biological control and freshwater alien invasive species management. The research chair is co-hosted by the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity and Rhodes University.

“Essentially that’s what’s keeping the water weed programme in South Africa afloat,” she said, adding that profits from the CBC’s international consulting work have helped cover running costs.

The CBC also received R1.5 million from Rand Water to implement biological control on the Vaal River Barrage reservoir, to tackle the invasion of water lettuce and water hyacinth. Last year, the coverage was nearly 400 hectares, mostly water lettuce, and is now only 1.34ha. It is being controlled by the water lettuce weevil.

“Working with Rand Water and the local community has been amazing,” she said. “The water lettuce is hardly even a problem. Every plant you see has got the biocontrol agents on it but the water hyacinth is a big worry.

“But even that is being kept under control through an integrated approach of manual removal, demarcating areas for biocontrol and setting up these big floating booms or curtains.”

“They are spraying herbicide in certain areas, all with legal general authorisations from the environment department and from the department of water and sanitation. It’s looking really good in comparison to a year ago and also if nothing had been done.”

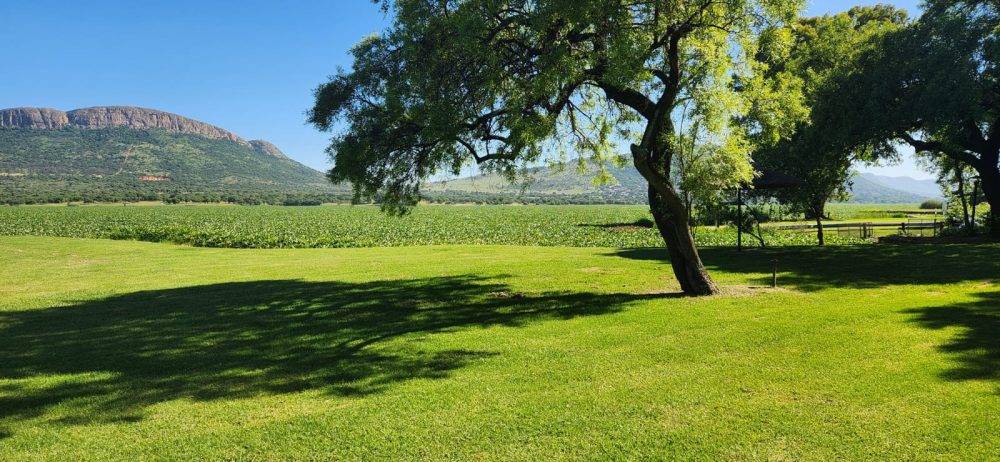

Lakeland at Hartebeespoort, taken by the manager, Theo Potgieter, on Wednesday morning.

Lakeland at Hartebeespoort, taken by the manager, Theo Potgieter, on Wednesday morning.

Infestations elsewhere in SA

In KwaZulu-Natal, the Inanda Dam, which is managed by uMngeni-uThukela Water, was previously heavily infested with water hyacinth. Now, with its integrated aquatic weeds management plan, which prioritises biocontrol, the coverage has dropped to below 10%.

“We’re working with fantastic people and everyone is working together,” said Coetzee.

At the Bronkhorstpruit Dam near Pretoria, the water hyacinth coverage is 15% to 20%.

Megamelus scutellaris hoppers lay their eggs only on water hyacinth.

Megamelus scutellaris hoppers lay their eggs only on water hyacinth.

“We’ve got community rearing stations there as well and it hasn’t increased to the extent it could have in the absence of biocontrol. They are also hoping to see a crash fairly soon, or a whole lot of damage [to the water hyacinth],” she said.

“The other big problems are Vaalkop and Roodekoppies Dams [in North West] and we have huge amounts of water hyacinth in the Eastern Cape in the Bridle Drift Dam, Lang Dam and the Buffalo River.

“In the Western Cape, all those beautiful wetlands such as Princess Vlei, Swartvlei and then in the actual Strandfontein Sewage Works, which is a declared Ramsar wetland and a wetland of birding importance, there are huge amounts of water hyacinth.”

She spoke of how the Blesbokspruit, near Springs in Gauteng, is so heavily polluted from mining waste that the hoppers are unable to take root.

“I’ve got a PhD student working there and the heavy metals in the water, in the sediment and in the plants is insanely high,” said Coetzee. “We can’t get the biocontrol agents to establish and we are looking at whether the heavy metals are toxic to the insects, and is it the insects themselves or is it their gut microbiomes.”

For now, the CBC sends as many biocontrol agents to infested waterways as it can. “The only thing we ask is whoever requests the insects pays for the courier because it’s R2 000 a shot and we can’t afford that.”

Biocontrol, she added, does not aim to eradicate an invasive species, but to reduce its population to a manageable level. “However, in the absence of water nutrient remediation, water hyacinth will continue to proliferate each season until the seed bank is depleted.”