African leaders are often involved in difficult, dangerous and costly games of “elite management” at the most senior political levels. (Graphic: John McCnn/M&G)

COMMENT

Aid professionals and policymakers working to address conflict in Africa argue that governance is fragile and disorder is rife because regimes are politically exclusive, allowing only narrow representation in government. The solution, they contend, is regimes must become more inclusive of their country’s diverse political identities, because exclusion is tied to conflict, while inclusion can create prospects for peace.

This prevailing wisdom is wrong.

The argument is flawed in two fundamental ways. First, African regimes are frequently characterised by high and sustained levels of ethnic and regional inclusion in cabinets and political parties. Second, even where there is a high level of inclusion, regimes still experience high rates of conflict, often driven by militias hired by powerful political elites. Political exclusion is bad politics, but political inclusion does not create peace by itself.

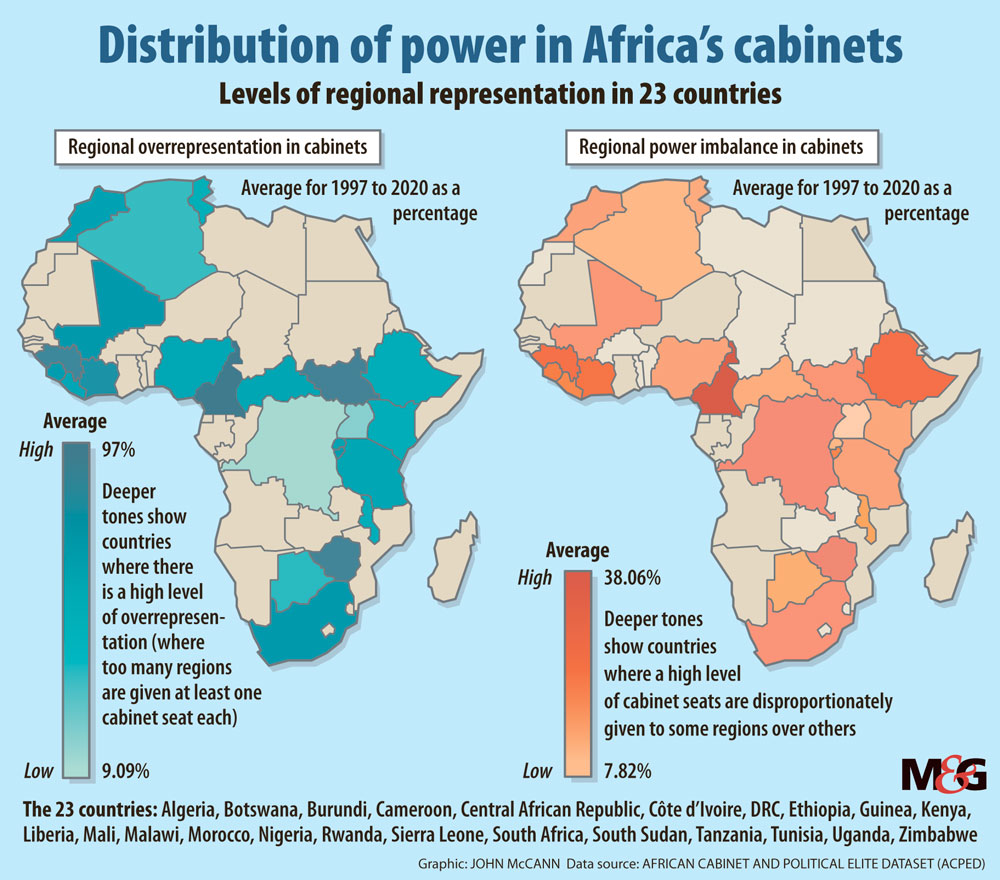

The African Cabinet and Political Elite Dataset (ACPED) has tracked each minister in every African cabinet for the past 20 years and is now compiling and releasing information on cabinets for 23 states, collected on a monthly basis. The data includes each minister, their characteristics such as gender, ministry and which political, ethnic, regional and party groups they represent. From this database, we have created measures of how well represented each state’s ethnic and regional groups are in each cabinet, and how proportional the distributions of seats are to the populations of each group in the country. The metrics demonstrate which groups are over- or under- awarded positions of power.

The results indicate that African leaders are often involved in difficult, dangerous and costly games of “elite management” at the most senior political levels. Here are our main conclusions:

African regimes are highly inclusive. On average, cabinets have at least one member from more than 75% of the country’s ethnic and regional groups. We measure political and group identity and regional identity separately for each minister, and we presume that a minister from a specific group or region is considered a representative. In countries where there is a clear majority group — such as in North African countries as well as Rwanda and Burundi — regional claims are a stronger way to differentiate elites and build a representative government.

Ministry allocation is unbalanced to minimise internal threats. A leader composes a cabinet that is loyal and dependent to him (or her). Skills and merit are rarely the primary determinants of who gets positions. We can conclude that leaders are carefully composing cabinets for strategic purposes, including balancing threats and building loyalties to survive often dangerous elite competition in their coalition and regime. A president’s co-ethnics or those from the same region are given a few additional seats and have longer tenures by almost three years. These findings support an adage about modern authoritarianism that the key to keeping power is to spread it around. Giving too many seats to extreme loyalists is bad politics, and it places leaders in vulnerable positions with other power-holders.

But few ministers are allowed to hold real power for significant periods of time.

African leaders face a fundamental problem with senior elites: those who benefit the most from cabinet roles are also the most likely threat to the leader. Leaders remain at risk of removal by irregular means such as coups. Those threats come from inside cabinets. To mitigate them, a leader builds a cabinet that keeps powerful elites happy, but also includes many weaker elites representing groups or regions that pose little threat individually, but can become obstacles to stronger elites organising against the leader. Cabinet-packing, unbalanced and disproportionate powers and moving elites around are ways to manage the internal competition between strong elites.

Loyalty transactions are important. Loyalty is transactional, and so each minister incurs a cost and a benefit. Elites offer a bridge between leaders and citizens: leaders need those citizens to vote, support and legitimate their rule. Leaders likewise require elites to broker this support during elections. The number of cabinet ministers increases in the months before elections, and then plummets because many are quickly fired afterwards. These short-term elites often have no agenda, staff, budgets or governance role: they are there only to signal a leader’s “support” for a group. This is a costly exercise in buying loyalty, but it results in leaders’ often winning elections in countries where they don’t seem publicly popular.

African cabinets are volatile. This is bad for governance, but good for internal politics. More than half of all 3 916 ministers recorded in the ACPED project have a tenure of five years or fewer. Nigeria has the shortest ministerial tenure at just over three years on average, meaning that Nigerian elites have the least time to fulfil public expectations. Uganda, Zimbabwe and Cameroon have had the longest serving ministers, at more than 10 years on average, but with little to show for this recurring cast of characters.

Many ministers are integrated during power sharing agreements to resolve conflicts, reward violence, announce initiatives demanded by the international community or to make cabinets appear to be cross-ethnic. Those ministers are window-dressing and not expected to influence the distribution of power in states. The highest number of different ministers are in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, Nigeria and Guinea. Population size, and government reach have little to do with how many elites get a chance to eat.

The combined effect of widespread representation, selective imbalance, cabinet packing and volatility are that regimes are more focused on playing a political game than on effectively governing a state. The way many leaders stay in power is by managing threats and loyalties, and curtailing the ambition of internal challengers. Although elites are resilient to these games, countries rarely are.

Dr Clionadh Raleigh, a professor of political geography and conflict at the University of Sussex, is the director of the African Cabinet and Political Elite Dataset and of the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd recently completed his doctorate at the University of Sussex and has managed the ACPED project since its inception.