Protest leader: Imam Mahmoud Dicko addresses a huge crowd in Bamako on June 5 (Photo: Michele Cattani/AFP)

On July 3, arguably the two most powerful men in Mali greeted each other in a reception room somewhere in Bamako. The room was lined with leather sofas; as they spoke, the national flag hung on a pole behind them.

Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta is the president of Mali. His guest that day was Mahmoud Dicko: the influential imam who represents the greatest threat to Keïta’s presidency.

After their meeting, as he left, Dicko addressed the president’s cameraman. He sounded optimistic. “We talked about everything that concerns this crisis and the country in general. I think that with the will of everyone and of all the parties concerned, we will, inshallah, find the solution.”

A president under fire

President Keita – or IBK, as he is commonly known – faces no shortage of crises, or challenges to his authority.

There are the Islamist militants in the north, contained only by the presence of a massive international peacekeeping force. Their reach extends to central Mali, exacerbating intercommunal tensions that have already been sharpened by the impact of climate change on access to land and water. In the south, where more than 90% of the country lives, endemic poverty and food insecurity has fuelled widespread anger towards the government, with the Covid-19 pandemic worsening the situation.

Multiple corruption scandals have not helped any of these tensions, or instilled confidence in IBK’s government, which has been in power since 2013.

Against this backdrop, Dicko has been able to channel public frustration towards the state with an approach that resonates widely: he advocates for moral values and good governance; calls for unity and divine assistance; and encourages reconciliation between ethnic and religious groups.

Nor is he afraid to criticise the president. “The head of state no longer has the physical and mental skills to run the country. Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta must leave,” Dicko said last month, according to Le Monde Afrique. This is not usually the kind of sentiment that gets you invited to meet the president, but IBK cannot afford to ignore Dicko.

Earlier this year, Dicko masterminded protests against Prime Minister Soumeylou Maiga, in response to a devastating wave of violence that swept across central Mali last year. After 60,000 people packed into a Bamako stadium to demand his resignation, Maiga duly resigned in April – along with his entire cabinet.

Just two months later, Dicko launched the June 5 Movement – an anti-government umbrella group that brings together religious leaders, civil society groups and the coalition of opposition parties. With his support, the movement staged several protests in Bamako and other cities, mobilising tens of thousands of people. The movement has called for the dissolution of parliament, and some – although not Dicko personally – have demanded IBK’s resignation.

An aerial view shows protesters gathering for a demonstration in the Independence square in Bamako on June 19, 2020. – Imam Mahmoud Dicko, one of the most influential personalities in Malian political landscape, called for a political march to be held after the Friday prayer, against Malian president Ibrahim Boubacar KeÔta and his government. (Photo by MICHELE CATTANI / AFP)

An aerial view shows protesters gathering for a demonstration in the Independence square in Bamako on June 19, 2020. – Imam Mahmoud Dicko, one of the most influential personalities in Malian political landscape, called for a political march to be held after the Friday prayer, against Malian president Ibrahim Boubacar KeÔta and his government. (Photo by MICHELE CATTANI / AFP)

This round of demonstrations were sparked by the contested results of parliamentary elections in March and April, which were narrowly won by the ruling party.

The kingmaker

Dicko has been a major player in Mali’s politics for many years.

Both his father and grandfather were well-known Muslim leaders, and he studied Islam in Mauritania and Saudi Arabi before returning to Mali in the 1980s. He rose through the ranks of various religious organisations – always outspoken on politics and governance, as well as religious issues – and was elected as head of the High Islamic Council in 2008.

Despite his education there, Dicko has never embraced Saudi Arabia’s ultra-conservative Wahhabist interpretation of Islam, and does has never endorsed violent jihad, according to Africa Confidential. “Dicko insists that he does not regard an Islamic republic model as suitable for Mali and dismisses suggestions that he is a Wahabbist. But while he is fully accepting of a secular state structure and legal regime, he remains a firmly conservative advocate of religious values in family matters and personal behaviour,” the magazine explained.

Infamously, in 2009, Dicko mobilised protests to defeat planned legislation that would have extended more rights to women. He is also vociferously opposed to homosexuality.

For Bakary Sambe, the director of Timbuktu Institute, the rise of Imam Dicko in the Malian politics “is the symbol of the failure of the political elite”.

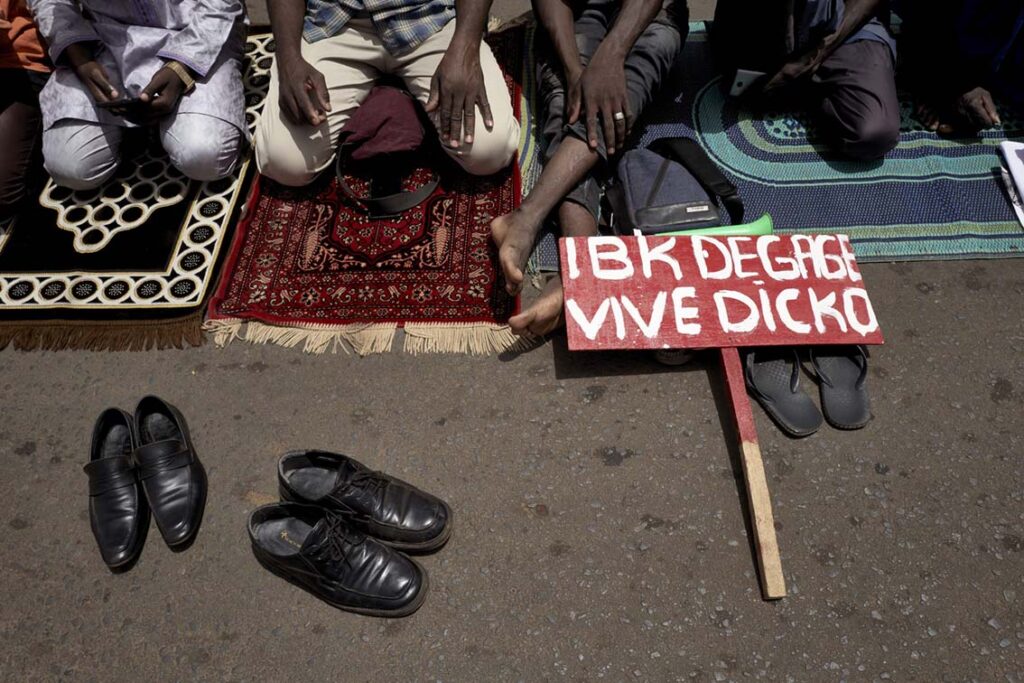

Praying for change: Protesters observe Friday prayers during a rally in Bamako (Photo: Michele Cattani/AFP)

Praying for change: Protesters observe Friday prayers during a rally in Bamako (Photo: Michele Cattani/AFP)

Alex Thurston, an academic at the University of Cincinnati who specialises in Islam and politics in West Africa, explained: “A lot of Malians feel that the top politicians are stale and have run out of ideas and solutions for Mali. Meanwhile there seems to be a lot of good will toward the leading clerics, who are seen as not quite as tainted by politics as Keita or other longtime politicians”.

No wonder the president is worried – and the meeting with Dicko did not appear to help.

Shortly afterwards, the opposition coalition released a statement in which it reaffirmed its “determination to obtain by legal and legitimate means the outright resignation” of the head of state. Protests continued through the week, culminating in huge demonstrations on Friday – ongoing at the time of publication – where protesters reportedly attempted to storm several government buildings.

If they get their way, then speculation turns to who would succeed IBK. For all his influence, Dicko is considered unlikely to put his own name forward – in this instance, the kingmaker may indeed be more powerful than the king. As he told Jeune Afrique in 2019: “I am not a politician, but I am a leader and I have opinions. If that is political, then I am political.”

This article was written for The Continent, the new pan-African newspaper designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. It will appear in the Saturday July 11 edition.