AFP/Shanon Jensen)

In an era of “vaccine nationalism,” the world’s only plan so far to secure poor countries their share of Covid-19 vaccines is still no guarantee, experts warn.

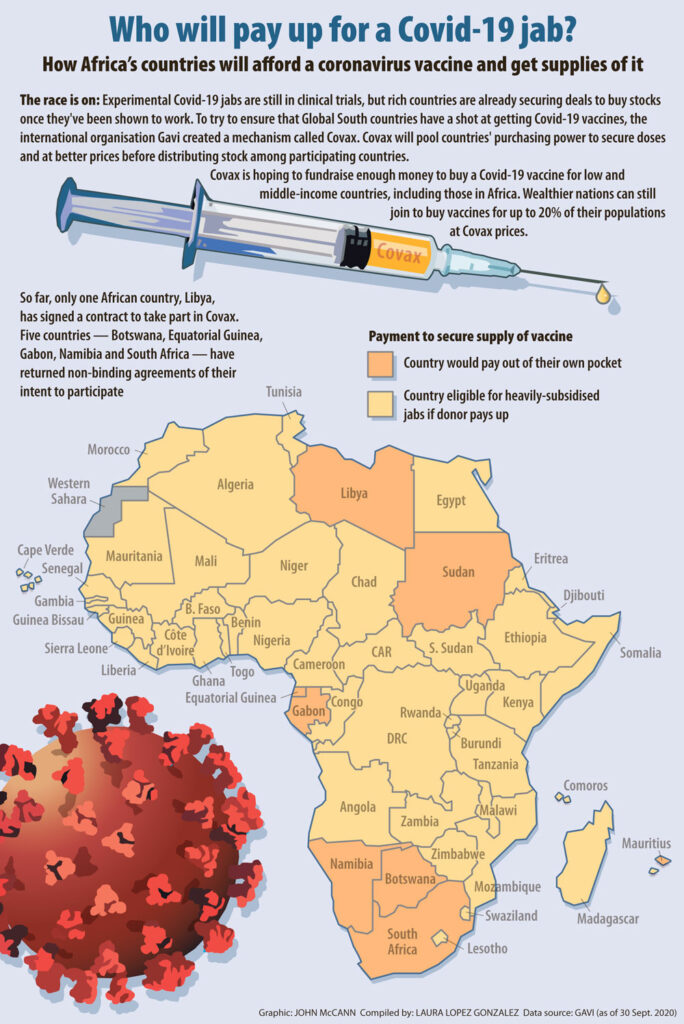

In April, the vaccine alliance Gavi and others launched the Covax initiative aimed at pooling countries’ purchasing power to secure a minimum of affordable vaccines for participating countries. Donor funding will ideally allow the poorest nations to receive jabs for a heavily subsidised price.

But late last week, Indian and South African representatives penned a letter to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). What they wrote in the note is at the centre of the single biggest question of the world’s latest pandemic: Will Covid-19 vaccines reach the world’s poor?

Members of Gurukul congratulate Oxford university through painting at Lower Parel after COVID-19: Oxford vaccine successful in early human trials, on July 21, 2020 in Mumbai, India. (Photo by Satish Bate/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

Members of Gurukul congratulate Oxford university through painting at Lower Parel after COVID-19: Oxford vaccine successful in early human trials, on July 21, 2020 in Mumbai, India. (Photo by Satish Bate/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

Covax draws on Gavi’s success with a similar 2005 initiative to introduce the pneumococcal vaccine to prevent childhood killers such as pneumonia and bacterial meningitis. The project rolled out the jabs quickly in Gavi-supported countries and saved lives. Still, independent reviews of the project point out it was not designed to spur market competition or local vaccine production in the Global South that would have lowered vaccine prices.

Doing either would have involved pharmaceutical companies sharing intellectual property around the pneumococcal vaccine, including patents and manufacturing technology, humanitarian organisation Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has pointed out.

Data from the US’s International Vaccine Access Center shows that more than a decade after Gavi’s pneumococcal vaccine project, almost one in four countries globally still don’t have access to that vaccine, largely because of cost.

Meanwhile, no pharmaceutical company has committed to sharing intellectual property with the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Covid-19 technology access pool, South Africa and India write in their letter. The WHO is hoping companies will step up to voluntarily license drugs, equipment and vaccines to other manufacturers to meet global demand.

MSF has asked Gavi to push for open licenses for the Covid-19 vaccines.

“In its spirit, [Covax] is a very admirable idea,” MSF senior vaccines policy adviser Kate Elder told the G20 Civil Society Summit this week, “but it seems to be falling prey to some of the global political dynamics that we see in other global health initiatives.”

Intellectual property rights were the focus of South Africa and India’s recent letter to the WTO in which the pair asked the body to waive some intellectual property protections during the pandemic and that are set out in its agreement on trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (Trips). This would allow nations to, for instance, manufacture or import a patent-protected invention, such as a vaccine, the head of South Africa’s Health Justice Initiative Fatima Hassan explains.

In theory, these kinds of allowances already exist for very poor nations and countries experiencing public health emergencies as under the WTO’s 2001 Doha declaration and what’s commonly known as Trips flexibilities.

But trying to use these flexibilities, Hassan warns, has been easy nor without its consequences historically.

The United States, for instance, has threatened to use Trips flexibilities against some pharmaceutical companies domestically but has not supported other countries to do the same.

South Africa and India’s plea for a waiver is unlikely to be well received by the US or the pharmaceutical industry. Still, if successful, it could allow countries in the Global South to make use of Trips waivers and flexibilities without incurring pressure from the US or pharmaceutical companies.

“If you get the waiver or this kind of concession from the WTO it could make it more difficult for Big Pharma then to challenge governments,” Hassan explains.

She says the irony of South Africa’s stance internationally is that amendments to South African law to make it easier to use Trips flexibilities and prevent frivolous patents at home have stalled for nearly a decade.

She says: “In South Africa, we could just fix our patent laws.”

What is Covax and why should I care?

What is it?

Covax is an initiative led by three international organisations: the vaccines public-private partnership Gavi, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (Cepi) and the World Health Organisation (WHO). The trio hopes Covax will ensure that all countries can access a Covid-19 vaccine — when scientists find one.

As of 2 October, 42 Covid-19 vaccines were in human clinical trials, according to the WHO.

How does it work?

Covax is hoping to pool participating countries’ purchasing power to secure doses of Covid-19 vaccines and negotiate better rates. Ninety-two low- and middle-income countries will get these jabs for a heavily subsidised price — provided that Gavi and partners can fundraise at least $2-billion. So far, the initiative has raised at least $700-million, according to Gavi’s website.

Poor countries will be asked to pay up to $2 per dose, assuming an eventual vaccine needs two doses to be effective, Gavi’s board recently decided. Initially, it had promised poorer nations jabs for free.

Gavi says the initial aim is to have two billion doses available by the end of 2021, which should be enough to protect high-risk and vulnerable people, as well as frontline healthcare workers. Covax is striving to make sure that every country can vaccinate 20% of its citizens.

Why do we need Covax?

When a pandemic of the H1N1 influenza virus — commonly known as swine flu — hit in 2009, richer countries hoarded vaccines, says researcher and Oxfam senior policy adviser Mohga Kamal-Yanni.

The United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and the European Union have already secured more than 4.2-billion doses of potential Covid-19 vaccines, Kamal-Yanni says. She adds that this is enough to vaccinate 20% of their populations almost eight times over, assuming one dose of a Covid-19 jab was enough to protect people from infection.

Is it just for emerging countries?

No. Richer countries such as Namibia, Botswana and South Africa can participate in Covax, buying their own vaccines through the initiative to access lower, Covax-negotiated prices. This can happen in one of two ways: countries can commit to purchasing a certain number of doses and pay $1.50 per dose upfront or 15% of the total cost per dose.

Alternatively, wealthier nations, particularly those who may have already secured some stocks of vaccines, can pass on buying some brands of vaccines in favour of others. Gavi explains that countries like these will pay a higher upfront price than their peers, but ultimately the cost of jabs will be the same in the end regardless of how much nations pay upfront.

However, the United States and Russia have said they will not participate in Covax. All three countries are home to companies producing Covid-19 vaccines. China announced it would take part late last week.

During the 2009 outbreak of H1N1 influenza, Cambridge University researchers found that high-income countries producing vaccines refused to export jabs until domestic needs had been met.

However, Gavi tells the Mail & Guardian that Cepi has pre-existing agreements with some companies globally and if firms sold stocks to other nations first, it would be a breach of contract.