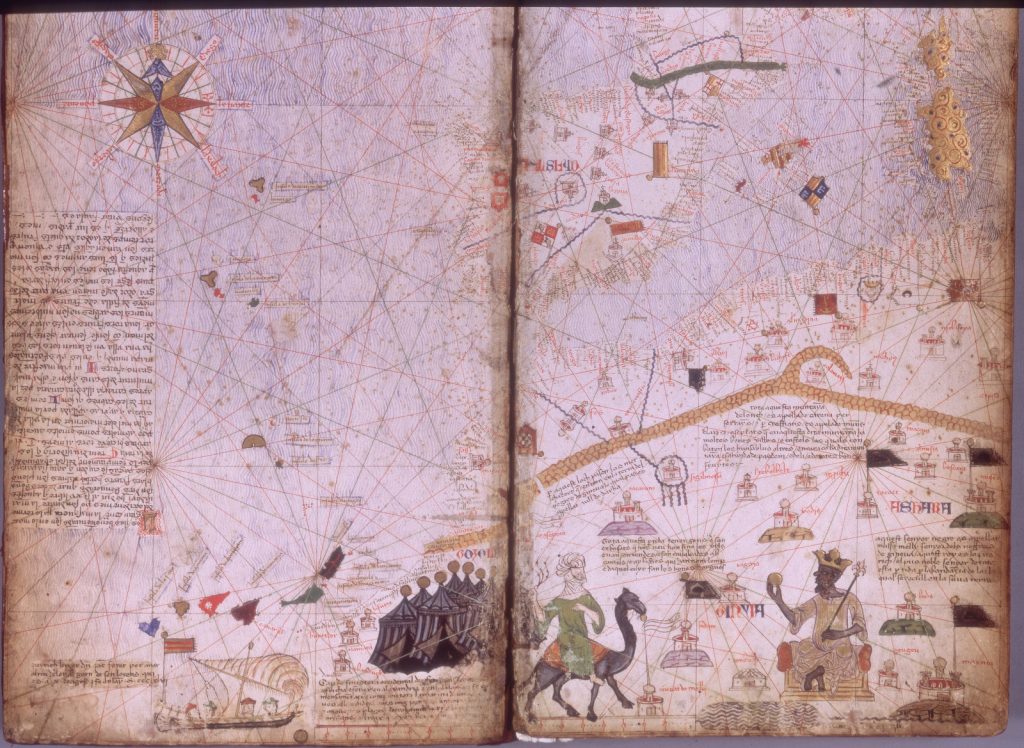

Rich as Mansa Musa: The king of Mali as

represented in the Catalan Atlas by the Jewish

illustrator Cresques Abraham in 1375. Photo:

History/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

The 1375 Catalan Atlas is one of the most significant maps in the Western mediaeval world. Centuries of exploration, theft and colonisation were built on its depiction of the world across the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

In its corner, an African ruler is shown sitting cross-legged on his throne, adorned with a robe and pointed crown. In one hand he grips a sceptre; in the other he holds a golden orb up to the sky.

The caption (once translated) reads: “This black ruler is named Musse Melly (Musa of Mali), lord of Guinea. This king is the richest and noblest ruler of this whole region because of the abundance of gold that is found in his lands.”

It is the earliest surviving map to depict Mansa Musa, the ruler of Mali between 1312 and 1337. His empire encompassed modern-day Mali, Senegal, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania and the Gambia.

Its wealth was built on gold. Its legacy was enshrined in an ambitious building scheme, centred on Timbuktu after Musa annexed it as part of a campaign where he conquered his neighbours.

That city would become a crucial focal point of the Islamic world. Bringing in architects and scholars he met on his travels, he built repositories of knowledge — Djinguereber Mosque and Sankoré Madrasa University stand to this day.

The Great Mosque at Djenne in Mali – near Timbuktu

The Great Mosque at Djenne in Mali – near Timbuktu

Musa’s legacy features prominently in the British Library’s Gold exhibition (on until 2 October), which looks at the power of the malleable yellow substance across history. The displays show how important West Africa has been to world history, a role that has been all but erased by the triumph of Western historians.

In the 14th century, nobody had more gold than Musa.

This was largely unknown as the gold crossed the Sahara on caravans, putting their producers far away from the people who would use it. Shipping routes around the western bulge of Africa had not yet flourished. In an attempt to change this, to learn about the world and as his own pilgrimage, Musa went to Mecca in 1324.

The trip spawned legends of his unfathomable wealth. Accounts would speak in awe of the ruler who travelled through their lands in a grand caravan containing tens of thousands of slaves, civilians, soldiers and camels laden with gold bricks. On the way he stopped in Cairo, Egypt. There, it was said, he gave to the poor, hoarded everything of fancy at the bazaars and even took the time to commission the construction of multiple mosques.

His profligacy was so great that the price of gold was devalued and the local economy beset by inflation for years afterwards.

On his return, Musa focused on building Mali as a centre of learning.

A Photograph of Mansa Musa, King of Mali on a map of North Africa circa 1375. (Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images)

A Photograph of Mansa Musa, King of Mali on a map of North Africa circa 1375. (Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images)

But his story was recorded by historians north of the Sahara. First it was those he met while he was in Cairo, then in maps long after his death. Musa — a symbol of the prosperity of the region — continued to be depicted, invariably bedecked in bangles and other gold accoutrements. One Italian map, produced around 1529, portrays him with white skin, playing a kind of fiddle.

The incongruity notwithstanding, its caption demonstrates the genuine reverence the West had for Musa and his kingdom.

“This king Mansa Musa rules the province of Guinea and is no less prudent and knowledgeable than powerful,” it reports. “He has with him excellent mathematicians and men versed in the liberal arts, and he has great riches.”

The depictions of wealth in Mali would lead European countries to creep down the African coast, initially trading their wares for the region’s gold. This trade helped to finance adventures further afield, to Asia and the Americas. It would eventually lead to the sale of millions of Africans — a trade that underpinned the dramatic explosion of wealth in Europe, driving that region’s colonialism and the pillaging of Africa for gold and anything else portable.

This article first appeared in The Continent, the pan-African weekly newspaper produced in partnership with the Mail & Guardian. It’s designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download your free copy here.