Dire situation: A busy street in Madagascar's capital Antananarivo. The country has seen a sharp rise in Aids cases and deaths. ©UNAIDS 2024.

The world has made significant gains in the fight against HIV in the past two decades.

While there was no treatment for HIV at the beginning of the pandemic 40 years ago, more people are living healthy lives as medicines have been rolled out more widely. Today, globally, 29.8 million of the 39 million people living with HIV are on treatment (76%) compared to 7.7 million in 2010.

Most people on treatment (93%) are virally suppressed, which means that they cannot transmit the virus to other people. However, gains made against the HIV pandemic are fragile in many low-income countries where international and domestic funding is lacking and many people are still waiting for treatment.

In Eastern and Southern Africa, the region most affected by the Aids pandemic — with more than 20 million people living with HIV — a number of countries are lagging behind in their HIV prevention and treatment efforts.

In Madagascar and South Sudan, a cocktail of problems, including a lack of international and domestic funding, means that Aids continues to claim lives.

This tragic situation also poses a direct threat to global efforts to end Aids by 2030, in line with the UN sustainable development agenda.

For example, Madagascar has recorded a 151% increase in the number of new HIV infections since 2010 and a 279% increase in Aids-related deaths during the same period. In addition, just 18% of the estimated 70 000 people living with HIV in Madagascar had access to treatment in 2022 and 3 200 people died of Aids-related illnesses.

Madagascar, which is one of the poorest countries in the region, has also been hit by a series of natural disasters, including chronic drought in the south and a series of cyclones, making it difficult for the country to recover economically and mount an effective HIV response.

According to the World Bank, natural disasters cost the country’s economy 1% of gross domestic product every year, taking away resources that could go into strengthening essential health services.

Dire situation: A busy street in Madagascar’s capital Antananarivo. The country has seen a sharp rise in Aids cases and deaths. ©UNAIDS 2024.

Dire situation: A busy street in Madagascar’s capital Antananarivo. The country has seen a sharp rise in Aids cases and deaths. ©UNAIDS 2024.

Malagasy authorities are equally worried about the HIV situation in the country. According to Dr Rivomalala Rakotonavalona, the director general of preventive medicine at the ministry of public health, “the number of new HIV infections is increasing in Madagascar”.

Compounding the problem of rising new infections the authorities are missing the full picture because there is a lack of reliable data due to weak systematic surveillance systems and stock outs in HIV testing kits at some clinics and other health facilities.

Rakotonavalona says the rise in new HIV infections has been unrelenting. “We’ve been seeing this for several years now. But … Madagascar hasn’t conducted national seroprevalence surveys; the last one was carried out in 2008 and the HIV prevalence rate was still less than 1% at the time.”

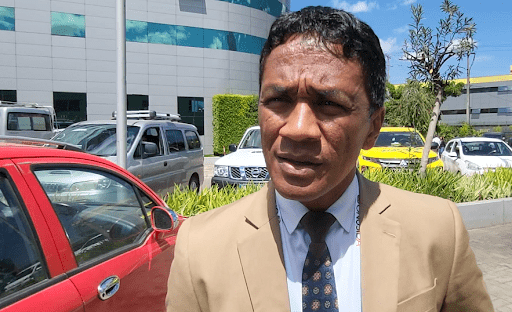

Concern: Dr Rivomalala Rakotonavalona, Madagascar’s director general of preventive medicine at the Ministry of Public Health. ©UNAIDS 2024.

Concern: Dr Rivomalala Rakotonavalona, Madagascar’s director general of preventive medicine at the Ministry of Public Health. ©UNAIDS 2024.

The UN is worried that Madagascar is unable to boost its HIV prevention and treatment efforts and that the pandemic could negatively affect the country’s development agenda. HIV disproportionately affects young people, especially young women and girls.

“The youth is the workforce of tomorrow. When that group is being affected by HIV and we are not doing anything about it, it is an economic problem for us tomorrow because that workforce is going to be affected by HIV and that is going to reduce productivity, increase morbidity and therefore reduce the economic potential of the country,” said UN resident co-ordinator for Madagascar Dr Issa Sanogo.

VIDEO OF UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR HERE

A lack of funding is also threatening to derail the HIV response in South Sudan. While the numbers of new HIV infections have been levelling off in the country, HIV prevention is at risk due to insufficient funding to end the pandemic. There are an estimated 160 000 people living with HIV in South Sudan.

People who inject drugs remain particularly vulnerable to HIV infection and drug use has been identified as one of the biggest contributors to new HIV infections in Indian Ocean countries such as Madagascar, Mauritius and Seychelles.

However, some Indian Ocean countries have in the past demonstrated the value of well-funded harm-reduction programmes, such as clean needle and syringe programmes and opioid agonist maintenance therapy.

The Joint UN Programme on HIV/Aids, UNAIDS, which leads the global Aids response, is working with countries such as Madagascar to identify gaps and strengthen their HIV responses to avert new infections and Aids-related deaths.

The rise in the number of new infections in a country such as Madagascar, for example, is in stark contrast to the downward trend in Botswana which has seen a 66% decline in new HIV infections since 2010 and a 36% decline in Aids-related deaths.

However, Botswana has benefited from significant investment in its HIV response over the years. As a result, the country — along with Eswatini, Rwanda and Zimbabwe — is on the path to end Aids through strong HIV prevention and treatment interventions.

In order to boost efforts to end Aids as a public health threat by 2030, during the recent World Bank Spring Meetings that took place in Washington, UNAIDS called for world financial leaders to ensure increased and sustainable investment in the global response to HIV and other health threats.

Robert Shivambu is a global communications officer at UNAIDS, which leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero Aids-related deaths.