Is Anton Kannemeyer’s new Bitterkomix collection, Pappa in Afrika, flagrantly racist or is it a lament for a continent ravaged by centuries of colonial rule?

Anton Kannemeyer is not racist. Like many South Africans and, in particular, recovering Afrikaners, he is caught up in a world that does not make sense. Not that apartheid made much sense. Eighteen years ago he joined forces with Conrad Botes to create Bitterkomix and boerepunk. Their abrasive humour ensured that the chink in the armour of Afrikaner nationalism developed into a gaping hole, a this should be seen as a progressive development.

I am less tempted these days to believe the outlandish claims by artists and critics that art is necessarily revolutionary, but if the Bitterkomix generation did convince some young men that apartheid was not worth dying and killing for, it was certainly a good thing. Whether that brand of acerbic humour is striking the right note today requires further reflection.

In Kannemeyer’s recently published Pappa in Afrika, an image titled Liberals (2010) is a retake of Zapiro’s Rape of Justice, except that in Kannemeyer’s version a ‘coon” is slitting the throat of a man one presumes is one of Kannemeyer’s alter egos. The alter egos populate the comic book. The rape victim screams: ‘Do something, Harold! These historically disadvantaged men want to rape me!”

The relationship between Zapiro’s cartoon and Kannemeyer’s is quite obvious, but with a few significant differences. Zapiro’s is a bit more literal in the sense that Zuma was accused and acquitted of rape charges, whereas Kannemeyer’s perpetrators are anonymous ‘coons”. Second, Zapiro’s victim is the mythological figure of Lady Justice in the form of a black woman. This is what sets Zapiro’s work apart from Kannemeyer’s in that the whiteness of the victim is a direct comment on the fears of whites generally, a theme elucidated in JM Coetzee’s Disgrace.

But the two cartoons are similar in a more fundamental way, in that criminality and deviant behaviour are directly identified with black masculinity. Zapiro’s may be a bit more blunt than Kannemeyer’s more tongue-in-cheek approach. That there are no women and white perpetrators in Zapiro’s Rape of Justice is also telling. There is no Jesse Duarte and there is no Carl Niehaus — both of whom were Zuma supporters. Although the treatment of the subject is different, white fear lies at the heart of both Zapiro’s and Kannemeyer’s work. But white fear is nothing new. It is what sustained and made apartheid possible in the first place.

Apartheid, in both its ideological and administrative manifestations, made one’s place in the world quite clear; social roles were narrowly defined. For many South Africans, both white and black, it seemed the world had turned upside-down in the post-apartheid era. Even during Nelson Mandela’s presidency people across the colour divide were struggling to come to terms with a Constitution that gave women equal rights and increased protection for children and minors.

The perceived loss of power and identity that came with both political and, to some extent, economic changes has left white South Africans, in particular, with feelings of insecurity. On one end of the spectrum there are those who are preparing for war in paramilitary training camps and on the other you have cynical liberals who are constantly making buffoons of current leaders.

There is no doubt we are living in a country of excess. There is pervasive violence and rampant corruption and artists and journalists cannot be blamed for pointing out these horrors. But a number of traps are set against these crusaders of truth and justice. These are the tendency to reduce the African experience to a kind of pathology, the temptation of African exceptionalism, the equation of transgression with progressive politics and the blind spot of their own privilege.

African-American feminist bell hooks is also useful here for having coined the term white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy, which is even more instructive than simply to label someone as racist. It is also insightful for emphasising the connections and interdependence between these social forces that are often spoken about in exclusive terms. It is possible to critique not only the surface of Kannemeyer’s imagery, but also the underlying network of attitudes that underscores his art.

To a large extent the reasons negative images of Africa continue to be peddled not only by the right but also by liberals and so-called progressives is that they are compelling because they bear some resemblance to the truth and they have been internalised in our psyche and popular imagination. There are so many black and white South Africans who see immigrants from other African countries as being parasitic on South African ‘success”, which suggests that it is difficult or near impossible for South Africans to imagine that people from other African countries have anything to offer and that visiting or working in those countries can be anything but traumatic.

The first and most obvious temptation is to suppose that the only response people can and should have to colonial violence is murder and rape. The notion that oppressed people can have novel and even non-violent responses to racial violence is a trap that even progressive movements seem unable to escape from. In the rhetoric of films such as Birth of a Nation, this endemic violence is a sign not of colonial violence but of a less developed, uncivilised psyche.

Furthermore, post-independence kleptocracy and corruption are alternately seen by leftists as necessary and inevitable consequences of unequal power and capitalist exploitation and, by those on the right, as necessary and inevitable consequences of the loss of the steadying hand of the colonial master. In some cases it is evidence that the African subject is inert to modernity. In either case the anomaly of misrule and bad governance are assumed to be conditions from which Africans can hardly escape.

In this way the historical-materialist analysis that purports to be more politically aware than the essentialist notions of African experiences also has the tendency to pathologise African subjects as nothing more than prisoners of history and violence. Unfortunately for all their political savvy and attempts to be critical, these assumptions maintain that the cartoons of people like Kannemeyer are unable to subvert.

In the concluding pages of Adam Horschild’s Leopold’s Ghost, the author raises questions of what motivated the groundswell of criticism of Leopold’s excesses in the Congo and why similar excesses by other European powers, not only in other parts of Africa but also in the colonised world generally, did not elicit similar outrage. In the attempt to answer the question he notes that the movement for change in the Congo came on the back of the abolitionist movement. Paternalism and philanthropy in protecting defenceless Africans against the Arab slave trade gave King Leopold II a pretext to enter the Congo and to turn it into his personal fiefdom.

The idea that there is something special about Africa, even though putting a finger on exactly what that thing is often proves illusory, does not prevent people from insisting that it is there.

It is difficult to look at the excesses that continue to bedevil the continent and not come to the conclusion that there is something seriously wrong here. But it seems that it is equally difficult for us to acknowledge that there are millions of Africans who travel to other countries — not as refugees but as businessmen and women, tourists and scholars. It is also difficult to imagine that there are generations of Africans who have never experienced war, famine or a coup d’etat, or that there are millions of Africans that enjoy a middle-class existence.

One of the questions that Pappa in Afrika raises is whether art that is somehow transgressive or subversive necessarily implies progressive politics. Pappa in Afrika is awash with imagery of African atrocities, the buffoonery of its leaders (Idi Amin appears a number of times) and corruption, but also the complicity of the West. In the world of art, as in the world of political and social satire, evidence that the audience is offended is seen as affirmation that the medicine is working.

Courting controversy and notoriety has become the stock in trade of artists of the post-1994 era. This is especially true of white male artists. Challenging political correctness has been their rallying cry. Such notoriety has been interpreted as a sign of genius in itself without really interrogating the content of the work. Among these have been people such as Kendell Geers, Brett Murray and, more recently, collectives such as Avant Car Guard. But there is a reason we don’t go around calling people ‘kikes” and ‘kaffirs” in the street, even if it is done in the name of humour. But if some infantile artists do just that, we are supposed to say they are not racist.

In the accompanying essay in Pappa in Afrika, Danie Marais makes a spirited argument that Kannemeyer is in fact exposing white fears and the racism that inspires them. And the implication here is that, because he is making fun of or ‘exposing” these fears, he can’t be racist. Whether his use of racial stereotypes, subversive as it might be, is sufficiently removed from its source to make it transformative is a question we have to ask Kannemeyer. Personally, I am not convinced that they are.

In an interview with the Sunday Times, Zapiro, in defence of his Rape of Justice cartoon, claims he is not racist because his record in the anti-apartheid struggle ‘speaks for itself”. If we say that struggle leaders are to be held accountable for what they are doing now and that their struggle credentials are of little consequence, then by the same token we should hold Kannemeyer and Zapiro to the same standard.

In his postscript Marais makes the claim that Kannemeyer’s work should be welcome because the issue of race is one that is not openly discussed in South Africa. This is true, but talk of race and racism has consequences. In an economy in which wealth and privilege are still heavily in favour of whites, there are dire consequences for ‘race talk” for black people. But it is easy to talk about race as long as you do not mention that attaining social justice also means the necessary pain of having to give up wealth and privilege.

It is not that Kannemeyer is ignorant of the privilege that comes with being white. But acknowledging one’s privilege is not the same thing as acknowledging the responsibility that goes with it. In a world in which artistic freedom and creativity are rightly valued above the instrumentalisation of the arts, ‘responsibility” is a dirty word. I am the last person to advocate that an artist’s creativity ought to be stifled in favour of political correctness, but that is not to say one ought to celebrate the cynicism of arrogant and intransigent products of racial privilege.

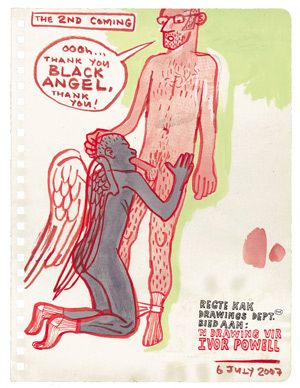

It is not only on the level of race that I find Pappa in Afrika reprehensible. In one of two works, titled Thank You, Black Angel, a black angel gives the artist a blowjob. Whether they are intended to be subversive or simply funny, much of the imagery is condescending. So what if the black people, men and women, in Kannemeyer’s cartoons lack agency and when they have any they act as agents of disaster — and then serve only to populate white fears and Kannemeyer’s fantasies?

It does not matter that they are offensive. It certainly does not matter that he dredges up a host of racist imagery and stereotypes. Indeed we are supposed to look and laugh — because ‘Anton Kannemeyer is not racist”.

Khwezi Gule was formerly the curator of contemporary collections at the Johannesburg Art Gallery. He is now chief curator at Hector Pieterson Memorial. Pappa in Afrika is published by Jacana Media