The outcome of the ANCs long-awaited KwaZulu-Natal conference was a win for the Thuma Mina crowd. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Nomusa Mthethwa's incredulous questioning of her experiences at a South African university ("How could I have failed varsity?", Mail & Guardian, January 11-17) calls into question the commonplace assumption that the quality of schooling is all-important in predicting success in higher education.

Although I would never deny that probably the majority of South African schools offer our pupils much less than they need and deserve, my experience of working in the field known as "academic development" for many years suggests that Mthethwa's experiences are not so unusual. Every year, I speak to students who are just as puzzled at the way the high marks and ongoing success they became used to at some of the best schools in South Africa are now so elusive in their new academic environment.

The instinctive response to students' low performance is to cite their newly found freedom — as Mthethwa indeed does in her allusion to partying and missing lectures. But many of the students who end up in my office are conscientious in the extreme. They have often been high performers at school because of this very trait and their lousy marks on the last test or for the last assignment confuse them all the more because of this.

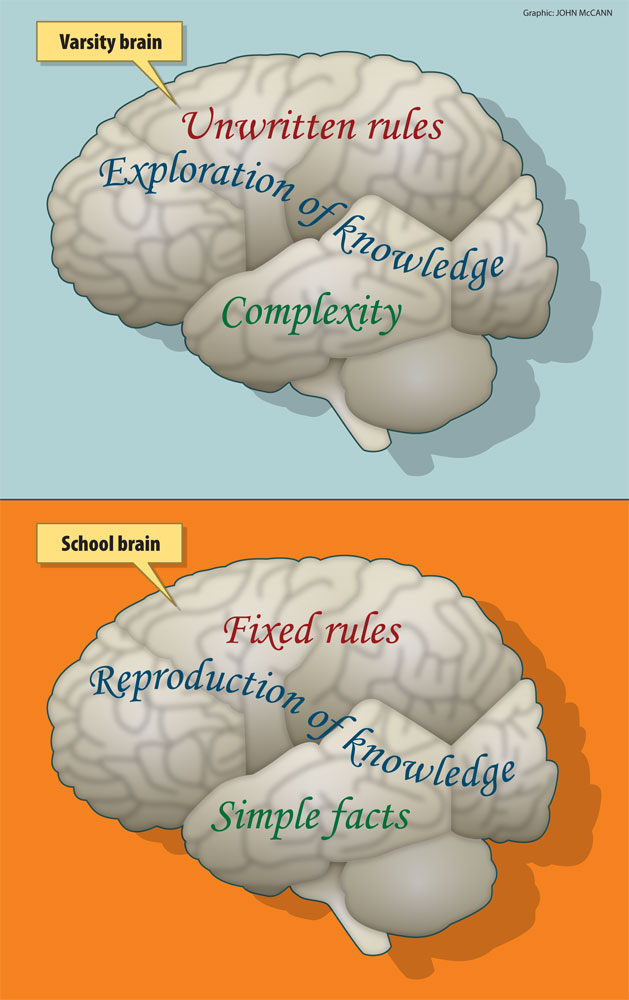

No, my money goes on another observation made by Mthethwa in accounting for her experiences — the idea that "university is a completely different ball game; a game whose rules are never taught" in any school, regardless of its quality.

Many of my academic development colleagues have been arguing this very point for decades. Universities are sites of knowledge production. Schools are places where that knowledge is reproduced — but only after it has been "recontextualised", as British sociologist Basil Bernstein puts it. And, as a result of this process, the very nature of knowledge is changed.

Years ago, I was astonished to come across research that compared the number of "hedges" (words and phrases such as "seems", "may", "might" and "could possibly") in school textbooks and academic texts on the same subject. The schoolbooks had hardly any of these words and phrases but the academic texts were full of them.

Lost in translation

What had happened, then, was that the uncertainty and the provisional nature of academic knowledge claims had been "lost in translation". The school textbooks presented knowledge as simple fact — not as something that could "possibly" or "arguably" be the case.

What does this say for the way pupils learn to read and learn in schools? Years ago, I was called to my own son's school and told that he couldn't read. This time it was my turn to be incredulous because I knew my son read (and wrote) extensively at home. I knew because we had taught him to read and write, and we read and wrote with him.

When I asked the class teacher what she meant, I was shown a comprehension exercise my son had done. The "comprehensions" many of us remember from school required the reader to respond to questions on the basis of the reading of a short text. The answers to the questions were in the text and the task of the reader was to find them.

My son didn't do this. He used his knowledge of the world and his knowledge of other texts, as well as his reading of the comprehension passage itself, to respond to the questions. In doing this, he was close to "academic" reading and writing — practices that involve a constant weighing of the claims and evidence in many different sources in order to arrive at a new claim of one's own.

My response was to go home and teach my son the "rules" for comprehension passages. A few quick lessons and suddenly his "reading" improved.

Academic literacy

But who teaches students in our universities the "rules" for the kinds of reading, writing and learning they need to do? If the schools aren't teaching them then it surely must be the responsibility of the universities themselves?

Some universities certainly do try to take on this responsibility. Courses in academic literacy and study skills abound, particularly at foundation level. So why wasn't I surprised when, at a conference recently, I heard an academic complaining that her students still could not read or write even after they had done a course in academic literacy?

I wasn't surprised because I think reading, writing and learning in academic contexts are complex and that courses that try to "fix" students by offering a set of generic "skills" just don't take into account that complexity. I can read, write and learn in higher education, my field of study. I can't read, write or learn in physics or psychology or management. To be able to work in these fields, I would need to immerse myself in them and, preferably, to have someone point out a few of the "rules" as I did so.

The problem there, though, is that, for academics, the knowledge making implicit in reading and writing and other practices is a tacit business. They know the "rules" for making knowledge but they aren't conscious of them and, as a result, can't and don't point them out to students.

Some of the most exciting work done in relation to teaching and learning in South Africa has involved teaching and learning specialists working alongside mainstream academics, observing and asking questions in order to try to "unearth" these rules. Cecilia Jacobs did this with a group of her colleagues at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology and my own colleague, Judith Reynolds, has done this with anthropologists at Rhodes University.

More recently there has been an explosion of work in what is known as the "sociology of knowledge" — work done by Suellen Shay and Kathy Luckett at the University of Cape Town, for example.

Only scratching the surface

But we are still only scratching the surface of what is to be known about academic knowledge and academic knowing, so what of Mthethwa and the many others like her?

Well, I would say that she has made an enormous leap in recognising the existence of the "rules" of the ball game she hasn't been taught. Realising that there are rules means she is more likely to be able to work out when they are operating and even what they are. Realising she needs to know these rules might even allow her to ask her lecturers the questions that will prompt them to think about what they do and provide an explanation to her.

It may, as she wrote, take her an extra two years to get her degree but I reckon she's on her way — more surely than students who carry on doing what they have always done regardless of the lousy marks or who simply give up in despondency.

Meanwhile, she might like to look at a booklet Rhodes is offering all its incoming students this year, available as a free download at http://www.ru.ac.za/digitalpublications. Simple though the booklet might seem, it could at least offer a few insights to those elusive "rules" and the strange practices that emerge from them.

Professor Chrissie Boughey is dean of teaching and learning at Rhodes University