The law

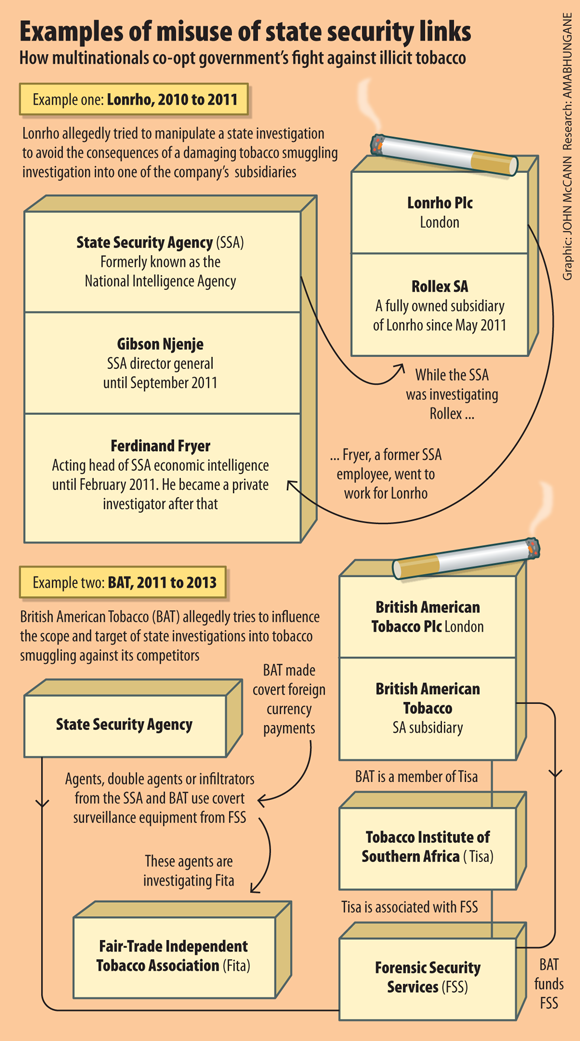

An amaBhungane investigation into the R5-billion-a-year illicit tobacco industry can reveal how two major multinational companies used their considerable resources to influence South African state security agencies to protect their commercial interests.

In one case, controversial African conglomerate Lonrho was able to sidetrack a criminal investigation of its logistics subsidiary, Rollex, which in 2010 had been caught smuggling truckloads of illegal cigarettes across the border from Zimbabwe.

The Lonrho example also calls into question the judgment and actions of former State Security Agency (SSA) director Gibson Njenje, who earlier this month launched a private intelligence company.

In another case, the dominant South African cigarette producer, British American Tobacco (BAT), appears to have parlayed its support for law enforcement into preferential access to state security structures – and, with that, the alleged capacity to spy on its competitors.

Both companies have denied any wrongdoing.

AmaBhungane has interviewed sources in Lonrho, state investigation agencies and BAT – who have sometimes acted as double or even triple agents – and reviewed documents, private correspondence and recorded conversations to piece together an astonishing snapshot of the penetration of private commercial interests into the state.

The evidence shows how vulnerable the security agencies are to manipulation by big private players with deep pockets, who do so often under the guise of “support” for official projects.

Case one: Lonrho

Two stories have their genesis in a police bust, on April 27 2010, of three trucks transporting illegal cigarettes.

The trucks belonged to Rollex, a South African transport company, 51% of which is owned by Lonrho.

Lonrho was once famously described as the “unacceptable face of capitalism” when it was run by Tiny Rowland and its board was graced by former British intelligence luminaries.

In 2010, Lonrho was led by David Lenigas and Geoffrey White, but its reputation for access to security agencies active on the continent remained intact.

White, for instance, was managing director of Oryx Natural Resources in 2002 when a United Nations panel accused Oryx of being a representative for covert Zimbabwe Defence Force financial interests.

Lonrho-controlled Rollex specialised in trucking fresh fruit and vegetables from South Africa to Zimbabwe, a business built by its founder and 49% shareholder, Paul de Robillard.

Rollex founder, Paul de Robillard

On that day in April, the trucks were returning “empty” from Zimbabwe. But, in fact, they were carrying a more lucrative load – cases of contraband cigarettes that were undeclared and untaxed and, therefore, very profitable.

Cheapies

The economic logic of cigarette smuggling is relentless.

In South Africa, as elsewhere, steep sin taxes comprise the major part of the cost of a pack of cigarettes. Find a way of avoiding paying those duties and the profits are on a par with narcotics.

But the risks are low: being caught smuggling earns little more than a fine.

Combine this with a semi-lawless neighbour, Zimbabwe, which produces tobacco, and the economics have propelled a succession of small players to carve a niche in “cheapies” – low-cost brands, often backed by creative ways of avoiding the prying attentions of the South African Revenue Service (Sars).

Today, the industry body representing the established cigarette brands, the Tobacco Institute of South Africa (Tisa), estimates that the illicit trade represents about 30% of the market.

The big players, particularly BAT, have hit back by pursuing an aggressive campaign to support action against the traffickers, including by funding Tisa’s favoured private investigations firm, Forensic Security Services (FSS), to the tune of about R50-million a year.

That campaign includes a seat on the Illicit Tobacco Task Team, which includes representatives from BAT, the Hawks, crime intelligence, the SSA and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), but not Sars.

Much of the focus is on the small players, who are blamed for most of the contraband activity.

But, controversially, the structure gives BAT access to state intelligence and the ability to influence who the state targets among its direct competitors.

Rollex and Delta

In 2010, the focus of the task team was on a cigarette manufacturing company, Delta Tobacco, one of several companies believed to be outlets for the big Zimbabwe tobacco and commodity barons, such as John Bredenkamp and Billy Rautenbach.

During that year, intelligence reports seen by amaBhungane suggested that Rollex – and specifically De Robillard – was linking up with Delta to create a one-stop cigarette operation including growers, manufacturers and distributors.

Banking records suggested that Rollex and related companies were doing millions of rands of off-the-books transactions, including bartering South African liquor for Zimbabwean cigarettes.

At that time, Sars suspected that the three trucks and their cargo of cigarettes were just the tip of a massive scam that could result in crippling customs and excise penalties.

Meanwhile, BAT lodged formal criminal complaints against Delta and Rollex.

Lonrho strikes back

This time, however, the task team was dealing, in Rollex, with an entity that had its own multinational backing and intelligence access through its parent company, Lonrho.

Lonrho did not appear to notice the truck and tobacco seizures in April or the possible implications.

In May 2010, Lonrho bought the 49% of Rollex it did not already own and retained De Robillard to continue to run what was ostensibly one of Lonrho’s most profitable divisions.

Lonrho also appeared to engage a secret weapon – Ferdie Fryer, then the acting head of commercial intelligence for the SSA.

Several meetings were held between Fryer and the legal counsel to Lonrho, Michael Bennett, at which it was apparently agreed to treat Lonrho as an innocent victim of De Robillard’s activities, despite the fact that the investigation was at an early stage and there was no clear evidence to suggest Lonrho or its directors knew of the activities at Rollex.

At a meeting in December that year, Fryer said that he was speaking on behalf of Njenje, as the head of the SSA domestic service, and that he was “mandated to negotiate” a deal with Lonrho.

Former State Security Agency director Gibson Njenje. (Photo: Oupa Nkosi)

According to notes of the meeting, Fryer told Bennett that “the South African government cannot afford to burn Lonrho on its investment” and agreement was reached that Lonrho and its reputation were to be protected “at all costs”.

‘Sidelining Sars’

About the same time, Njenje called an extraordinary meeting of the heads of the crime-fighting services. Those present included the Asset Forfeiture Unit’s Willie Hofmeyr, Hawks commander Anwa Dramat, Financial Intelligence Centre boss Murray Michell and Sars deputy commissioner Ivan Pillay.

According to a source familiar with the contents of the meeting, Njenje introduced a report, presented by Fryer, which claimed to have evidence of corruption by senior members of Sars.

But Sars claimed it had recordings that showed that the allegations were engineered by a group of individuals, including a manager of Rollex, who had been targeted by Sars for their involvement in tobacco smuggling.

Sars said that a key contact of the individuals behind the claims was Graham Minnaar, a former SSA employee and a long-time source for Fryer.

With the recordings and the questions about Minnaar’s role, Sars was able to counter the allegations and Njenje’s and Fryer’s presentation was cut short.

The mysterious Minnaar

AmaBhungane reported in 2011 how Minnaar played the role of agent provocateur in an alleged attempt by former Malawian vice-president Cassim Chilumpha to arrange the assassination of the country’s president, Bingu wa Mutharika, in 2006.

Minnaar later was revealed as a state witness in the case against Chilumpha.

Minnaar’s role as a former member of the SSA was revealed at the Ginwala inquiry into former national director of public prosecutions Vusi Pikoli, where it emerged he had accompanied Malawi’s chief prosecutor to a meeting with Pikoli to seek official help in gathering evidence against Chilumpha.

Minnaar this week denied he was party to the 2010 allegations against Sars. “I was not involved in that investigation … Anyone suggesting [I was] either received false information or is busy with some sort of agenda.

“I’m a political risk consultant. Some of my clients trade in the tobacco industry …

“The only fleeting connection that I have to that matter is a former colleague of mine [who] played a role … Ferdi Fryer …

“He asked my opinion on some matters because I used to work with him on some issues when I was still engaged with the SSA, and it was not in any way substantive.”

Fryer and Lonrho

Neither Fryer nor the SSA appeared daunted by the rebuff from Sars, though Fryer resigned officially from the SSA at the end of February.

But he continued to “represent” the SSA in negotiations with Lonrho after his resignation.

On April 11 2011, Fryer made an extraordinary presentation to a project team that included another SSA manager, a senior prosecutor, advocate Johan van Heerden and senior police officers.

According to minutes of the meeting, Fryer disclosed that a co-operation agreement had been reached with Lonrho.

“Fryer explained the rationale behind the decision for the co-operation, especially as a result of Lonrho’s foreign investment into South Africa and the negative impact of it suffering as a result of the rogue elements within its South African subsidiary.”

Fryer also told the meeting that Sars was uncooperative and compromised, and therefore should be excluded.

“Fryer confirmed the commitment to Lonrho to assist with protecting its assets and reputation.”

Thereafter, the SSA and the NPA shared with Lonrho its very detailed intelligence report on Rollex and related entities, including confidential eyewitness, whistle-blower evidence.

The NPA declined to comment, saying that the report was compiled by the Hawks.

A delayed raid

Sars, unaware of the “co-operation agreement” with Lonrho, was pressing for a raid on Rollex.

It is understood that both Njenje and Van Heerden wrote to Sars urging a postponement, arguing that a raid would derail a sensitive investigation.

Meanwhile, information from the confidential witness affidavit that had been provided to Lonrho was allegedly used by Lonrho to confront De Robillard, tipping him off.

When the raid on Rollex eventually happened sometime around September 2011, it was in terms of a search-and-seizure application that had been drafted for the police by a private advocate representing Lonrho. Very little was found, notably because there had been a robbery about two weeks before during which the company’s computers were stolen.

The NPA, however, denied the allegation that a private advocate for Lonrho had drawn up the warrant, saying "it was based on an affidavit by the SAPS investigating officer, [and] drawn up by NPA employees".

Allegations but no responses

Two sources involved in the events claim that Fryer was subsequently remunerated by Lonrho or its agents.

Correspondence shown to amaBhungane by a confidential source suggests that Njenje was made aware of Fryer’s apparent conflict of interest, but it seems the spy boss did nothing about it before his departure from the SSA in September 2011.

According to the same correspondence, Njenje issued an instruction that Fryer’s alleged relationship with Lonrho was not to be shared with the case officers of the SSA.

AmaBhungane asked Njenje to respond to the chain of events, which, it was put to him, suggested he acted to protect Fryer or Lonrho.

Attorney Ian Small-Smith, on behalf of Njenje, told amaBhungane: “Our client is unable to comment on matters which stem from his tenure at national intelligence [the SSA] because … he signed secrecy and confidentiality agreements with his employer when he left the state.”

Similar questions were put to Fryer, including about his alleged conflict of interest. He declined to comment, referring amaBhungane to the SSA.

SSA spokesperson Brian Dube would only say: “As a matter of policy, we do not comment on our existing operations.”

It appears the criminal cases to be made against Rollex and De Robillard are moribund.

The NPA said it "cannot comment" on the status of the investigation against Rollex and de Robillard.

Sars provided amaBhungane with general details of the work it has done to combat non-compliance in the tobacco industry, but did not comment on the specific incidents referred to in this article.

De Robillard has previously denied the allegations of cigarette smuggling but did not respond to calls or questions sent to him through his new logistics venture, Afriag.

Whatever the explanation, the interventions by Lonrho, Fryer and Njenje kept the potentially devastating claims against Rollex at bay until Lonrho was sold to new Swiss investors in May last year for R2.9-billion.

The new owners said they were “unable to comment on activities and issues of the previously listed company”.

Lenigas, the former Lonrho executive chairperson, in turn batted the issues back to the new owners.

Lenigas is back in business with De Robillard. He did not respond to the charge that Lonrho was able to influence the South African authorities to keep the smuggling investigation quiet until the sale of the company was concluded.

But he claimed to have raised “over half a billion dollars globally for African business investment over the last decade”.

Perhaps the last word on the interplay of intelligence and money should go to Njenje.

His private intelligence firm, Foresight Advisory Services, boasts several former high-profile spooks on its board, including Mo Shaik.

At the launch, Njenje told journalists: “We will go where we’ll get paid for the services we provide.”

Case Two: British American Tobacco

In November 2012, Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe launched a characteristically direct broadside at an adversary: this time it was at British American Tobacco.

Accusing it of using dirty tricks against its Zimbabwean competitors, Mugabe warned: “If this is what you are doing in order to kill competition and you do it in a bad way, somebody will answer for it.”

Few people took much notice, perhaps because Mugabe was defending one local cigarette company in particular, Savanna, which is controlled by his nephew by marriage, Adam Molai.

But BAT denied the charges levelled against the company in Zimbabwe.

A spokesperson said BAT “strongly denies any involvement in industrial espionage or illegal activity that may be linked to other local tobacco manufacturers”.

Yet documents obtained by amaBhungane show that, about a year before, in about December 2011, Forensic Security Services (FSS) had recruited a controversy-dogged former South African National Defence Force recce, Michael Peega.

After leaving the military, Peega worked undercover for Sars, but was fired after he was implicated in rhino poaching.

The documents suggest that FSS sent Peega to Zimbabwe to set up a base and deploy surveillance or tracking equipment.

Affidavits signed by Peega state: “I am an adult male who in a consultancy capacity renders a service to the Tobacco Institute of South Africa, aimed at assisting law enforcement agencies to curb the trade in illicit cigarettes.”

Peega was also suspected of being the source of a document hawked around by Julius Malema in February 2010, which accused Sars of targeting allies of President Jacob Zuma (among whom Malema then counted himself) using the covert Sars unit Peega was once a member of.

By December 2011, Peega was working for FSS and the affidavits were apparently required to account for cash that had been given to him to set himself up in Zimbabwe.

Attempts to contact Peega this week for comment were unsuccessful.

FSS provides investigative services to Tisa and is led by a tough and shrewd former apartheid-era intelligence officer, Stephen Botha.

Botha declined to comment for this story, saying: “The terms of our services are governed by confidentiality agreements and, therefore, we are not at liberty to respond to your submissions or questions.”

British American Tobacco (BAT)'s Stellenbosch headquarters (Photo: David Harrison)

Fast forward to December 2013 and Peega has emerged as one of a number of BAT agents paid in a roundabout way: direct deposits are made into untraceable foreign currency cards by BAT’s global head office in London.

The evidence may prove embarrassing for the cigarette giant, which appears to be running a private intelligence network in Southern Africa enjoying active support from the SSA and other law enforcement entities.

Tisa is said to spend roughly R50‑million a year on services provided by FSS, though neither it nor BAT would confirm the figure.

BAT and FSS representatives, through Tisa, also sit on the multi-agency Illicit Tobacco Task Team, where critics say they get to drive the law enforcement agenda.

For instance, according to a source familiar with the task team’s work, a senior member of BAT United Kingdom, Allen Evans, has presented a detailed project proposal to investigate Gold Leaf Tobacco Corporation, always regarded as BAT’s biggest threat in South Africa.

BAT estimates that the illicit trade in cigarettes deprived the South African government and the Southern African Customs Union of a staggering R50-billion last year.

“Any information handed over to law enforcement agencies, when so requested, is done so primarily on matters related to suspected acts of illicit trade in cigarettes,” the company said in response to amaBhu-ngane questions.

“BAT (SA) remains committed to compliance with the country’s laws and supports free and legitimate competition.”

But according to information from former BAT agents, the interpenetration of state and private intelligence has gone further and has led to the infiltration of BAT’s smaller competitors.

AmaBhungane has learned that when the small players set up their own industry body, the Free-trade Independent Tobacco Association (Fita), in mid-2012, not only was the organisation riddled with agents but the SSA also bugged its first meeting using equipment and technical experts provided by FSS.

BAT (SA) told amaBhungane it had no knowledge of this allegation and therefore could not comment.

Some subsequent meetings were also monitored and, in some cases, people employed by competitors of BAT were secretly paid to report to it.

At least six individuals were supplied with Travelex foreign currency cards, which allowed BAT UK to transfer cash to these agents in a way that was not subject to the restrictions of foreign exchange and money-laundering regulations, either in the UK or South Africa.

It appears this may also contravene South African and UK tax legislation.

BAT denies any involvement in illegal activity: “BAT (SA) upholds and complies with all laws applicable to it and the company’s standards of business conduct,” the company said.

* This article was updated on Friday March 20 to reflect attempts to contact Peega for comment, and to include comments submitted by Sars and the NPA after the M&G had gone to print.

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Email [email protected]

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.