Widespread tuberculosis awareness campaigns can rein in its increasing transmission rates.

Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death by natural causes in South Africa. Yet most TB deaths are preventable. Political will, leadership and commitment are urgently needed to manage this public health crisis, which is out of control.

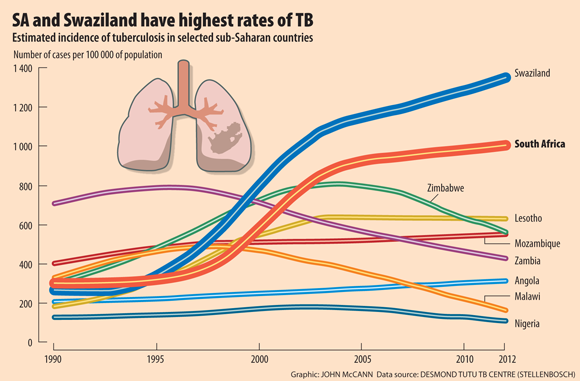

Although TB rates are decreasing worldwide, including on average in Africa, the World Health Organisation's Global Tuberculosis Report for 2013 notes that the estimated TB incidence in South Africa – already unacceptably high for many years – is continuing to rise.

The prevalence of TB in South Africa is now estimated to be more than 1 000 cases per 100 000 people, whereas in the US, Japan and Australia and in many countries in Europe, it is fewer than 10 per 100 000.

Between 2011 and 2012, South Africa was one of three countries (together with India and Ukraine) that had the largest increases in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), a form of TB that has become resistant to at least two of the main TB drugs used to treat it.

South Africa is a middle-income country, yet apart from Swaziland, we have the highest incidence of tuberculosis in the world; in other words, the number of people with TB per population a year.

The causes of the increase in TB in South Africa are complex and interwoven with poverty, inequality and a health system that does not function optimally.

I'm privileged. I have a job. If I cough for two weeks, then I say, "This isn't normal. It's affecting how I live my life." But if someone does not know where the next meal is coming from, and is really concerned that if she misses a day's work she could lose her job, then going to the clinic for a TB test is unlikely to be a priority.

Awareness

A range of initiatives, including education and awareness and ensuring that health services function optimally, is needed for this to change. And we can't do it without a concerted effort from all quarters: from government and academics to healthcare workers, employers and people in the community.

There have been some advances. The cure rate in Cape Town and in many parts of the country is slowly improving. But, while celebrating higher cure rates, we must acknowledge that we have a crisis. There are still enormous gaps.

We need to get the balance right. It should not be all doom and gloom: this paralyses people and they feel they can't do anything about the problem. But we need to take shared responsibility for the TB crisis.

Tuberculosis is spread by small droplets containing TB bacteria. These minute droplets can float around in the air for a long time. So TB is transmitted if a person with TB coughs, sneezes or even talks (or sings!), and someone else breathes in air containing these droplets.

The message that will help to prevent the transmission of TB is very simple. Anyone who coughs should cough into a tissue or handkerchief and anyone who coughs for two weeks or longer should be checked for TB. It's a message that everyone has a responsibility to carry.

Right to be tested

Firstly, everyone should know that it is their right to be tested for tuberculosis. People need to take the initiative to ask for a TB test, though it's easy to blame clinic or hospital staff for not picking up on TB.

Friends, families and colleagues also need to be aware of anyone in their circle who may have been coughing for two weeks or longer. They need to help one another by pointing out the symptoms of TB, encouraging people to get diagnosed and treated and offering to accompany them to the clinic.

Employers should allow employees to go to the clinic to be tested for TB – no one should lose their job if they have TB.

Clinic staff should take shared responsibility for TB. Nurses have a myriad competing priorities, but TB is the number-one killer in South Africa; they should be acutely aware of this. They should notice whether a patient is coughing, even if they've come into the clinic for a completely different ailment or are simply there to collect tablets. If a nurse sees someone who has come to the clinic to get their blood pressure checked, but they have also been coughing for some time or losing weight, the nurse should test them for TB.

If the test has been done, the healthcare staff must make sure the results become available.

From the receptionist and the nurse to the cleaner, absolutely everyone in the clinic should be on the lookout for TB.

Diagnosis

There have been welcome advances in South Africa in diagnostics, with the introduction of a rapid diagnostics test for TB through the new Gene Expert machines that have been introduced at government laboratories. This is a good move, but new technology on its own is not going to decrease our tuberculosis rates.

Most people in the country, whether rich or poor, know about the dangers of speeding or driving under the influence of alcohol. You see it on billboards, you hear it on the radio and see it on television. There should be similar awareness campaigns around TB and the need to go for a test if you've been coughing for two weeks or longer.

Politicians should be encouraged to raise awareness of TB as a health crisis by talking publicly about it throughout the year – not only around World TB Day on March 24.

The National Development Plan (NDP) lists progressively improving TB prevention and cure as one of its main health goals. The plan says strengthening a results-based health system should be a priority. We support the NDP's focus on obtaining credible data that is vital for decision-making.

It's estimated that only 22% of people with TB in South Africa are on treatment. This is because many people who have TB do not access healthcare services, and many of those with symptoms of TB who do access the system are not tested.

A quarter of TB patients not on treatment

In South Africa about a quarter of people who are diagnosed with TB are never started on treatment.

This should be addressed urgently because these people have accessed care; they have cost the government clinics money in both nurse time and diagnostic tests, yet they are not being treated.

We have made strides. There are a great number of people on TB treatment in South Africa, but there are even more people with TB who are not on treatment. They ride in taxis and public transport, walk around in shops or in their own homes – and they are transmitting the disease.

A combined effort would help to increase the number of people on treatment and would help to slow down transmission. This would also help children, who are particularly vulnerable and at greater risk of contracting TB if adults are not treated.

South Africa's greatest public health crisis can be managed – if we all share responsibility for it.

Professor Nulda Beyers is the director of the Desmond Tutu TB Centre, an academic research centre of the department of paediatrics and child health in the faculty of health sciences at Stellenbosch University