It's 7am. My leg is hurting. There's a burning pain running between my knee and hip. And I have to stand.

It's pouring outside. And the waiting room – if indeed that's what it is – is cold. It has chairs and benches in rows, and there are about 60 people waiting.

I am late. There's no seat left for me.

The Skinner Clinic at the Tshwane District hospital in Pretoria will open in only about 30 minutes.

I'm here because I need a referral for x-rays. I was in a car accident two years ago, and can't afford medical aid. My private-sector physiotherapist referred me to a private-sector orthopaedic surgeon, both of whom I need to pay in cash. The physio-therapist made it clear that I would need to visit the surgeon armed with x-rays, or he would not be able to help me.

But when I phoned Steve Biko Hospital to book an appointment, I was told that the hospital did not accept private-sector referral letters. I would have to get a public one.

So, here I am at the closest state clinic to Steve Biko Hospital to get my public-sector referral. Otherwise, I will have to pay the R2 000 it will cost to scan my right leg, right knee, hip and shoulder. For the shoulder, I also need a sonar scan.

In one of the chairs in the front row, an elderly woman dozes off. She arrived just before 6am. There is a notice board with faded posters promoting medical male circumcision and TB testing on the wall in front of the clinic's entrance. "Average waiting time: 170 minutes" one of the letters pinned on the notice board reads. (Hopefully I'll make it out in time for my 1pm meeting.)

Can I help you?

At 7.30am, a security guard takes a seat at the small desk by the door. "Sisi, can I help you?" she asks. I tell her it's my first visit to the clinic. She scribbles something on a tiny piece of paper and leads me to a row of wooden benches where I'm instructed to sit and follow the line.

At 8.55am, it has become apparent that I will be waiting much longer than the two and a half-plus hours indicated on the notice board. There is only one administration clerk registering first-time visitors and the queue is moving at a snail's pace.

It has been 20 years since South Africa's first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, introduced free primary healthcare for pregnant women and children under six in 1994.

Two years later, universal access to government clinics and community health centres was extended to all, making services at those institutions free for everyone, and free at state hospitals for selected patients.

According to the national healthcare facilities audit, South Africa has 3 880 public clinics, community health centres and hospitals, a number the ANC in its election manifesto undertakes to increase by 213 clinics and community health centres and 43 hospitals. Free healthcare includes antenatal care, certain vaccinations, HIV counselling and testing, and sexual and reproductive health services.

I'm starting to wonder whether my x-rays are included in the free services.

At 10.30am, I finally make it to the front of the queue.

By 10.45am, my file has been opened, and I can move to the next station. But it took much longer than I expected. Perhaps I should call the person I'm supposed to meet at 1pm and tell them I'm running late?

NHI

According to the government, the vision of the National Health Insurance (NHI) is to ensure that inequality is eliminated through good quality healthcare for all. This is emphasised in the NHI green paper, which states that access to healthcare "should be free from barriers" and that "everyone must be protected from the financial hardships linked to accessing these health services".

The Rural Health Advocacy Project at the University of the Witwatersrand points out, however, that the green paper "does not sufficiently explain how this protection is accorded, and how the barriers are eliminated".

The organisation says that poorer communities do not enjoy the benefits of free healthcare because of factors such as the cost of transport to get to the clinic.

"Fifteen percent of South African households live more than an hour from the closest clinic, and 20% live more than an hour from the closest hospital," it says. Furthermore, the quality and availability of services at healthcare facilities are cause for concern; for example, staff shortages translate into long waiting times.

At 11am, I'm led into an observation room, where a nurse wearing a pink uniform is busy with another patient at a desk. I am told to take a seat at the same desk, and told to take my jacket off. No privacy here.

The nurse tightens an inflatable armband around my upper arm without saying a word. Is that a blood-pressure meter, I wonder. But there is still no word from the nurse. Not to me, anyway. She's loudly talking to other nurses, also busy with patients in the room.

You need to use our doctors

I tell the nurse the reason for my visit to the clinic, but she's not really interested. "You can't take our scans to your private doctor," she says. "He needs to take his own scans. If you want to use our scans, you need to use our doctors."

Damn. So what am I doing here? The x-rays come with trademark restrictions?

Nonetheless, I am sent to another department.

It is 11.30am, and as I wait in yet another queue, I realise that half of my work day is over and I have to cancel all my appointments for the rest of the day because there's no telling how much longer I will be here.

At 12.10am, I discover there is a two-month waiting list for x-rays. But then I decide to act strategically, and start to cry loudly and openly.

The nurse reluctantly slots me in much sooner, for March 28 at 7am. It looks like I'm going to miss another day of work, though. The nurse says the queues are long. And here's the snag: I have to bring my payslip. "If you earn a salary, you have to pay," the nurse snaps.

Not free for everyone

Services at public hospitals are not free for everyone.

In 2000, the government introduced a uniform patient fee schedule as a guideline for billing for services at state hospitals.

The schedule divides patients into three categories: full-paying patients include those being treated by private doctors (that's me!) and select groups of foreigners (such as tourists or illegal immigrants).

The second group, the fully subsidised patients, are those who are referred to a public hospital by a state clinic (which is what I was trying to do), and partially subsidised patients are billed according to their income (which is what is about to happen to me).

I don't know how much a state hospital will charge me for the sonar and x-ray scans. I hope it's not R2 000. I'm also not sure my actions helped, as I didn't get a referral slip or appointment card. The nurse just snapped: "Come back here on March 28 at 7am. And wait."

So, as you're reading this on Friday, I'm probably waiting. And hoping. For help. Maybe the NHI will help me. Tshwane is, after all, one of the NHI's 11 pilot districts.

If I don't get my x-rays today, I might just have to apply for a bank loan to have them done privately. Because public healthcare might not be affordable or accessible to me.

SA's ART plan makes its mark

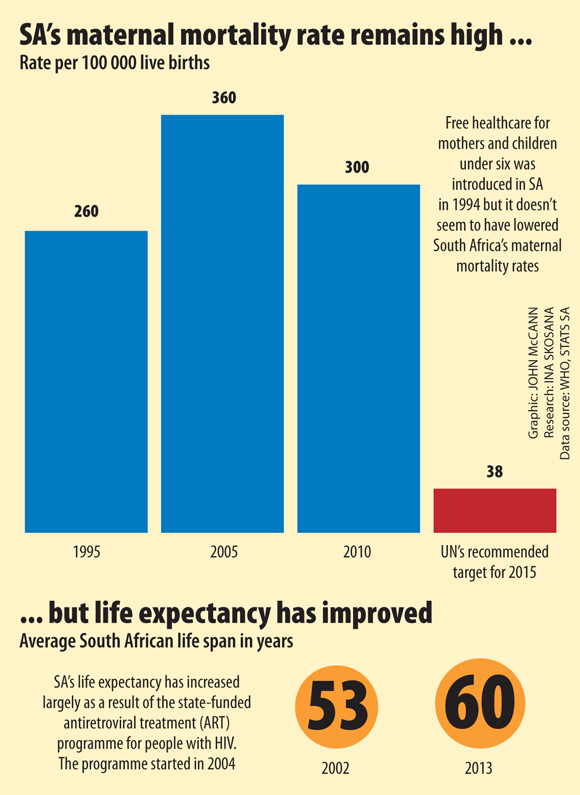

Although Nelson Mandela introduced free healthcare for mothers and children under six in 1994, it doesn't seem to have impacted on South Africa's maternal mortality rates. According to the World Health Organisation, the country's maternal mortality rates increased from 260 per 100 000 live births in 1995 to 360 in 2005 and then declined slightly to 300 in 2010. This is almost eight times higher than the United Nation's recommended target of 38 per 100 000 live births for 2015.

But a success story of South Africa's free healthcare is the antiretroviral treatment (ART) programme for people with HIV. It was initiated in 2004 following a 2002 Constitutional Court ruling that forced former health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang to implement a prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme for HIV-positive pregnant women and their babies. Today South Africa has the world's largest public-sector HIV treatment programme with 2.4-million people receiving treatment.

According to Stats SA, the country's life expectancy has increased from 53 in 2002 to 60 in 2013, largely as a result of ART.