UN peacekeepers in DR Congo. The country is seen as victim of 'distance decay' - the diminishing of state power as one moves away from the centre. State control of its territory is increasingly challenged in Africa.

The increase in “small wars” in Africa has lately been dominating the news out of the continent, but at this point they are happening mostly in ill-governed peripheries and contested borderlands.

The bigger story about them, though, is that they are challenging the concept of the unitary nation-state in Africa with its defined colonial borders.

Since 1990, there has been sustained reduction in the number of large-scale armed conflicts. Many of the old-school major guerilla movements like the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA), UNITA in Angola and RENAMO in Mozambique, SWAPO in Namibia, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front – iconic of the classic era of big civil wars – died out through military conquest or peace treaties.

A complex welter of diverse regional, religious and ethnic/clan identity politics and grievances drive most of the new insurgencies.

The primary objective seems to be to weaken, undermine or reconfigure the centralised nation-state through a protracted war of attrition that gradually bleeds its resolve and forces it to cede territorial control.

In some instances, military and political stalemate has created a state of de facto balkanisation that could prove difficult to reverse.

Under assault, therefore, is the very nature of the nation-state — its political legitimacy and credibility; its utility, future evolution and the integrity and inviolability of its borders.

It is therefore important to understand the wider context, especially the troubled career of the modern nation-state, and how the traditional concept of what it is and what it is for has evolved.

Retreat of Westphalia

Our notion of the nation-state and ideas about national sovereignty, territorial integrity and non-interference – the so-called Westphalian principles that have underpinned the conventional view since the 19 century – have been steadily eroding for a variety of reasons, not least, the rise in military interventionism.

Africa with its artificial and arbitrary borders, and for decades bedeviled by misrule and secessionist insurgencies, has been particularly more vulnerable to its corrosive impact.

The resurgent and widespread modern sub-national discontent and peripheral antipathy towards the centre is partly a product of the systematic assault on the ideas and values that have shaped the nation-state.

External borders are no longer sacrosanct or inviolable and, internally, the nation-state’s monopoly of territorial control is subject to contestation. The new insurgency feeds on this zeitgeist.

The common denominator that unites and animates the anti-centre politics of most of the new separatists, insurgencies and sub-national groups is an instinctive disdain for the inherent right of a central authority to exercise full functional and administrative control over its own territories.

Somalia’s case

No other African country has been as radically altered by “small wars” as Somalia. In three decades, it has been transformed from a united and centralised state into a deeply fragmented nation, a patchwork of large and tiny sub-national entities and enclaves, autonomously administered by clans and the militant group, Al-Shabaab.

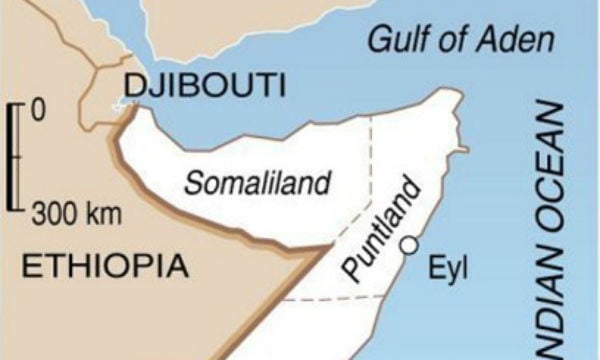

Somaliland, a northwestern province that was called British Somaliland in colonial times and which briefly forged a union with the rest of Somalia, broke off in 1991 following a popular referendum. Its independence is contested by Mogadishu and not recognised internationally.

A number of influential powers in Africa and beyond are known to be privately sympathetic to Somaliland’s pleas for recognition. They include South Africa, Ethiopia, Kenya and the UK. They are however unlikely to break ranks with the rest of the international community and would instead prefer to see the AU take the lead in determining the issue.

Since 1998, a number of regional administrations have emerged, such as Puntland in the northeast, Galmudug and Ximan and Xeeb in central Somalia, Jubba in the far south and the newly-created Three Regions State in south-central. The number of these administrations is likely to grow.

This proliferation has posed a major dilemma for the government in Mogadishu. Constitutionally, it is obliged to support decentralisation, but the clan identity politics driving the chaotic “federalisation” process has forced it to move to reverse the trend in the last one year.

The attempt by President Hassan Sheikh Mahmoud to seek a greater role for the state to influence and manage federalisation was initially resisted in the periphery and largely viewed as a stratagem to re-centralise the country.

Those concerns have somewhat eased following the negotiated deal–brokered by the EU and the regional grouping Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)– to engineer a “soft-landing” for the Kenyan-backed Jubba administration in Kismayo and the Three Regions State in south-central, but they have not disappeared.

A key player that has emerged in Somalia politics in the last few years is the militant group Al-Shabaab. Its territorial control has diminished since 2011 as a result of military action by the African Union peacekeeping force AMISOM, but the group still controls significant areas in south-central Somalia, which it administers tightly.

Unlike other groups in Somalia, Al-Shabaab’s philosophy of government was always centralist and monopolist.

Its vision is one of a strong, centralised Somali state that forms the nucleus of a future Caliphate. Consequently, and not unlike other transnational jihadi groups, it does not recognise existing international borders.

Sudan and DRC

Outside Somalia and, lately, Libya and Central African Republic (CAR), Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are today two of Africa’s most graphic illustrations of “small wars” states plagued by endemic armed insurrections and periodic pogroms in their vast peripheries.

Most of the violence in Sudan is in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, but there are potential trouble spots in the east too, where a truce with local ethnic rebels remains tenuous and discontent is rife.

In DRC, Kinshasa has been fighting a dizzying motley collection of low-level insurgencies on multiple fronts in much of the east for many years, especially the Kivus.

Despite attempts by the Kabila government to quell the rebellion through dialogue and military help from the UN peacekeeping mission, no breakthrough is in sight.

The actual functional territorial control of the regimes in power in Khartoum and Kinshasa has steadily diminished, with the proliferation of these localised insurgencies.

Sudan and DRC are classic examples of how mass discontent, conflict and violence are fuelled by “distance decay”, the term used by social scientists to describe how state “presence” and the quality of its institutions, structures and services progressively diminish the further one ventures away from the centre and the closer one gets to the periphery.

Borders and criminality

The new insurgencies are not just intent on redrawing borders, they are also proving adept at exploiting poorly policed borders to create safe havens and grow their strength.

A number of them are becoming transnational criminal syndicates and key players in the grey economy, raising millions of dollars in revenue from smuggling of contraband goods and narcotic drugs, people trafficking and kidnapping.

A recent report has highlighted how Nigeria’s Boko Haram has tapped into the lucrative kidnap-for-ransom racket by fellow jihadists in the Sahel-Sahara belt to augment its income from traditional sources.

Al-Shabaab was described in a recent UN study as a business conglomerate that has benefitted from the charcoal trade and the smuggling of cut-price contraband sugar into East African markets. There are also reports from conservation groups it may be involved in poaching and the illicit ivory trade in the region.

In DRC, the conflict is in large part fuelled by competition over control of areas with vast mineral resources. Many of the warring factions and their leaders are key players in the so-called conflict minerals, especially the highly lucrative rare-earth metals, used in high-tech industries.

The Sinai Desert is now said to be the favoured route of illegal African migrants seeking to enter Israel. The Bedouin rebels in the Sinai have been fighting government security forces in the last three years and have been implicated in many terror attacks across the country. These groups are said to be making huge sums of money from extortion and from acting as middlemen for people-trafficking syndicates.

Borders and resource competition

There is another dimension to the trend of commercialisation of armed conflicts that may have a direct impact on the tussle to reconfigure borders.

In a number of the conflict hotspots in Africa, usually in historically marginalised peripheries and contested borderlands, the discovery of huge reserves of hydrocarbons and minerals, raises the prospect of two plausible scenarios.

One, it could fuel “resource nationalism” and regionalism and embolden organised secessionist groups.

Two, it may incentivise dialogue to resolve conflict. Both trends seem to be emerging and it is not yet clear which will prevail.

In Somalia, the Nugaal Dharoor Valley believed to contain oil deposits and eyed by multinational oil companies, is situated on a region contested by Somaliland and Puntland and the scene of periodic armed skirmishes.

A new armed rebellion has been underway in the region since 2011 and a self-proclaimed state called Khatumo has been created to challenge both administrations.

In the Ogaden region of south-eastern Ethiopia, the recent discovery of huge oil and gas deposits triggered the first tentative moves by the state to engage the ethnic Somali ONLF (the Ogaden National Liberation Front) rebel group – a secessionist movement that has waged a lengthy guerilla war against the central government.

The talks – brokered by Kenya – have made very little progress. A recent incident in which an ONLF negotiator was abducted by Ethiopian intelligence operatives in Kenya may have damaged trust. But it is not yet clear whether the affair is a temporary setback or whether it has fatally damaged the chances for peace.

•ALSO READ: A changing map: How ‘small wars’ are redrawing Africa’s borders