Once upon a time, Lagos was the city where Afrobeat stars such as Fela Kuti and Fatai Rolling Dollar cast musical spells under tropical skies. Backed by dozen-strong live bands, their words incited live crowds into, musically speaking, launching Molotov cocktails at the palace doors.

Nowadays, a flood of sugary autotuned anthems threatens to drown that rich musical heritage, but a small but growing group of musicians is fighting against the tide. West Africa’s biggest musical export may now be politically vacuous Afropop, but some among the younger generation want to return to socially conscious music.

Often singing in pidgin and taking their cue from traditional religions, music and instruments, they meet each month in the grounds of a former colonial prison where the British tortured and hanged those who agitated for freedom.

“Afrobeat is more than just music; it’s a movement. It’s about politics, economics — all of that, in musical form,” said Seun Kuti, who grew up playing alongside his father, Fela, at his famous nightclub, the Shrine. Authorities razed the original site as Fela’s popularity grew on the back of songs that wove trance-inducing beats with a searing take on local realities. And, although Seun continues to play at the renovated Shrine, Afrobeat music today draws bigger crowds in Europe and the United States than at home.

The monthly Afropolitan Vibes night aims to revive a spirit of rebellion, however. “Until recently we artists would all have to meet in Europe — we would go to Paris, London, Berlin, to record,” said the event’s dreadlocked creator, Ade Bantu.

“The whole idea of Afropolitan Vibes is to bring it back to ourselves. We want to take all the complexity and coolness of being African and to connect it to the realities on the ground.”

On a recent Saturday night, several hundred sweating, foot-stomping, cheering fans watched Bantu open a show as the crowd was wreathed in pungent smoke and palm wine flowed.

Live big-band music that was once the fabric of traditional celebrations and events across West Africa began dying out during the late 1970s as imported sounds drowned the local market, and churches became the mainstay for musicians to earn their keep. In Nigeria many also struggled to accept Afrobeat’s rejection of Christianity and Islam in favour of traditional religion; the subject still raises eyebrows.

“People like to talk a lot about going to your roots, but then they don’t want to talk about religion,” said Emmanuel Owusu-Bonsu, one half of the Ghanaian duo Wanlov and Mensa, at another recent Afropolitan Nights show.

The pair’s musical film, rapped and sung entirely in pidgin, drew a shocked silence — and a few appreciative chuckles — when it depicted Buddha laughing as he played war games, while Jesus enjoyed a turnip-sized spliff with two flirtatious nuns. In another scene Count Dracula and Ghana’s trickster spider god, Kwaku Ananse, had an open-mic battle.

Elsewhere, others are also giving heritage a modern spin. “We’re like the town crier,” said Grammy award-winner Lekan Babalola, whose Eko Brass Band refers to the traditional Yoruba name for Lagos and whose members are deeply conscious of their city.

The 12 band members are from the city’s gritty Campos area, a home for returning slaves from Brazil, and their brass style walks the line between pre-slavery music and the sound that missionaries’ brass bands absorbed when they reached Lagos’s shores in the 18th century.

“Our message is to talk to our people first — that’s 180-million Nigerians. We have [Yoruba divinities] Ifa and Orisha to inspire us, and that’s what makes us different. Lagos has the stock exchange, the area boys, the culture, the history, the grit. It’s easy to celebrate it through music,” Babalola said. — © Guardian News & Media 2014

Revolutionary griot voice lives again

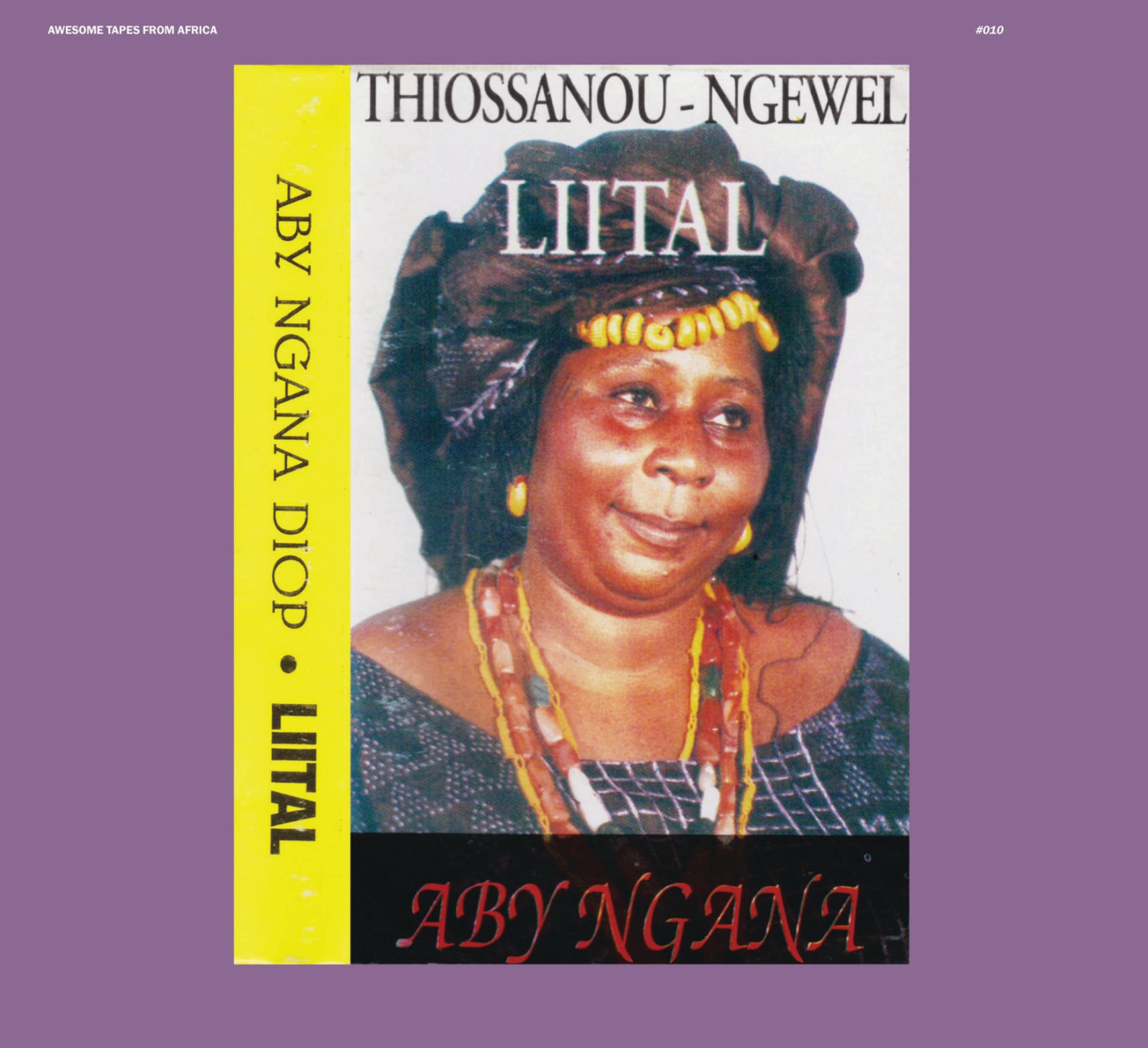

Littal by Aby Ngana Diop (Awesome Tapes from Africa)

Something for the more adventurous, this 1994 recording by Senegalese griot Aby Ngana Diop will turn heads at any party, as indeed Littal must have done during its few weeks of stardom. It wasn’t so much “what the hell is this?” back then but “oh yeah, Dieuleul-Dieuleul!” when her catchy hit was selected by a certain in-the-loop DJ at a Dakar nightclub.

Sadly, Diop died in 1997, surely confident that her one and only record had been consigned to history.

Diop was ground-breaking for pulling together two key styles. Primarily she had a griot heritage, something made more unique by her undertaking of taasu — a kind of ritualistic poetry that lends itself naturally to music.

Her infectious sense of fun also embraced mbalax (Senegal in the 1990s — what else would you listen to?), creating a style similar to rap by her natural pace, power and playfulness with the Wolof language.

And if her voice was loud, Diop’s percussive combination was cacophonous: get ready for claps, whistles, traditional drum rhythms and frantic, Nintendoesque keyboard bleeps.

Dieuleul-Dieuleul is a huge song by all proportions, and fully deserves this resurrection. More importantly, though, we glimpse here what made Diop such a sought-after taasu performer. Combine this sonic glimpse with her requisite charisma, stage presence and humour, and you have the complete female Senegalese griot. — Clyde Macfarlane

Littal will be released on September 2