Target: The media's obsession with President Jacob Zuma and his family makes 'objectivity impossible'

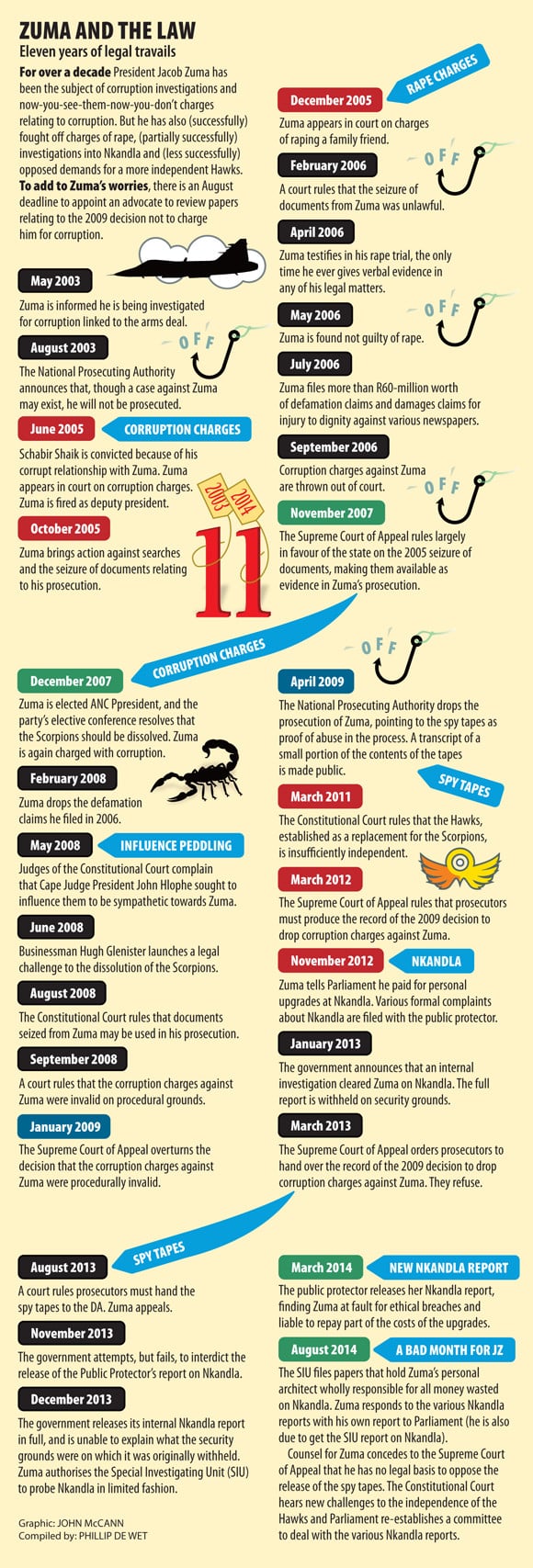

Three very different but intertwined issues are facing President Jacob Zuma at the moment. This is how they are connected:

The personal: Nkandla

A “reasonable percentage”. That is what public protector Thuli Madonsela declared, in March, that Zuma should repay of the costs of upgrades at Nkandla, on the basis that he and his family unduly benefited from state spending at the rural homestead.

What would be reasonable Madonsela did not find it her job to determine, but in the context of more than R200-million spent, anything on the larger side of reasonable could, in theory, bankrupt a man with an official salary of R2.6-million a year.

The Special Investigating Unit, on the other hand, has held Zuma’s personal architect Minenhle Makhanya wholly responsible for what it calculated at R155-million in wasted state money.

Now, according to Zuma’s considered opinion, it is up to the minister of police to determine how much he must pay back. Whether that decision stands could well be up to Parliament, though with a court review of the decision more than likely.

That, in turn, could end up in the Constitutional Court.

Although the amount of money involved is small, any payment exacted from Zuma would be interpreted as an admission of guilt, by opposition parties if nobody else, and would have a disproportionate political impact.

Zuma’s approach to dealing with Nkandla, which has at times included apparent disinterest and perfunctory attention, has been held as indicative of his approach to corruption in general.

The institutional: the Hawks

Though it came under his watch as ANC president, Zuma was not officially responsible for the disbanding of the Scorpions, the high-profile priority crime unit that was established under the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The process was started under Thabo Mbeki, and continued during the caretaker presidency of Kgalema Motlanthe.

But the switch to the Hawks, a unit located within the South African Police Service, is closely linked to Zuma’s rise to power; the ANC decision that the Scorpions had to go was taken at the same conference that ousted Mbeki in favour of him. And during his two terms in office, Zuma has been responsible for – to date – unsuccessful attempts to argue that the Hawks are capable of effectively combatting corruption.

Businessperson Hugh Glenister first attempted to interdict the disbanding of the Scorpions, and was joined by a long list of opposition parties that claimed attempts to do so were rooted in a desire to protect high-ranking ANC members from investigation.

That attempt failed, but Glenister’s efforts ultimately saw the Constitutional Court rule that a corruption-busting unit was an absolute necessity, and that the structure of the Hawks did not permit the unit to operate with sufficient independence to do the job.

This week counsel for Zuma again argued that the Hawks, under an amended law, are fit for the purpose of combatting corruption. Others still disagree, and the matter has become a litmus test for the Zuma administration’s commitment to fighting corruption in a government loaded with ANC deployees.

The critical: corruption charges

No issue has dogged Zuma as much as the (currently nonexistent) charges of corruption against him. In 2003 Zuma was informed that he was under investigation for alleged corruption relating to the multibillion-rand arms deal. By 2005 it seemed certain he would be charged, after his financial advisor was convicted of having had a corrupt relationship with him.

Judge Hilary Squires would later point out that he had not found a “generally corrupt” relationship between the two, a phrase that has been attributed to him even by other courts, but in a judgment that mentioned Zuma 471 times, he did find that Shaik companies made payments to Zuma in contravention of the corruption Act.

In 2003, NPA head Bulelani Ngcuka said there was a “prima facie case” against Zuma, but declined to prosecute. In 2005, new NPA head Vusi Pikoli said Zuma would be prosecuted; that case was struck off the roll in 2006 amid disputes about evidence.

At the end of 2007, papers were filed to reinstate the charges, but in 2009 acting NPA head Moketedi Mpshe dropped the prosecution again, citing the spy tapes.

Crises of leadership at the NPA and infighting within police crime intelligence (and the wider intelligence apparatus) have been linked to this sequence of events, with allegations that Zuma was prioritising his personal requirements of an NPA head, to wit executive-mindedness, above the needs of the organisation.