Gold Fields hired Gayton McKenzie to help it secure a mining licence.

When I start the recording app on my iPhone, it shows the date of the last interview I did with a musician. Almost two years ago, on November 1 2012, with blues/rock legend Piet Botha. I have in effect come out of quasi-retirement for the chance to interview Chris Chameleon, and I’m not sure why.

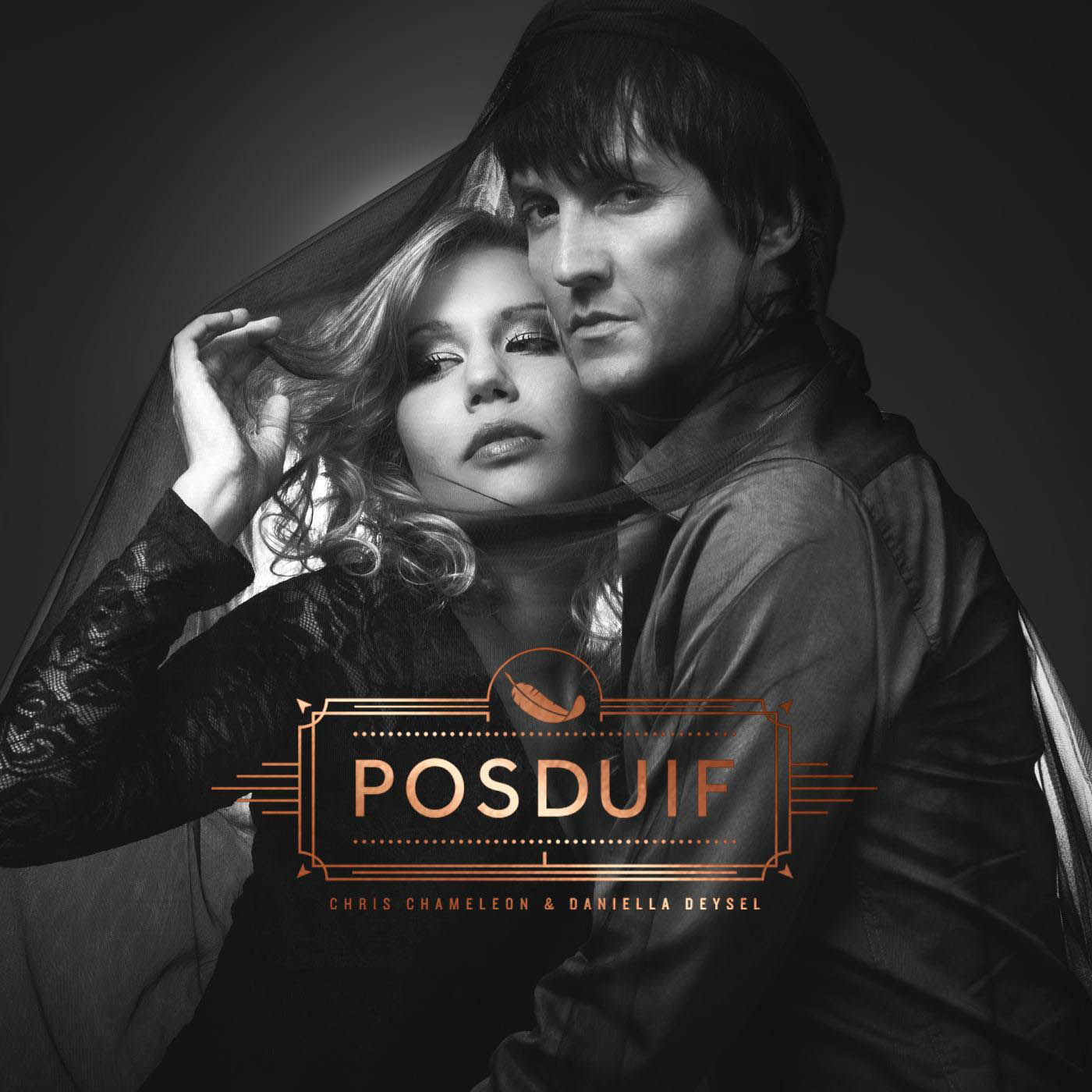

He himself expresses some surprise — he tells me he expected that I’d send one of our regular music journalists. It’s not that I’m overwhelmed by his new album, Posduif, and feel the need to testify to that, although it is a lovely collection of songs that I’m finding strangely compelling. It has something to do with Chris Chameleon as a symbol, a symbol of change, resilience, and the triumph of a peculiar art.

And with Chameleon as a musician who has managed to remain true to a unique essence, while at the same time firmly inserting himself within the adult contemporary Afrikaans market.

It’s also a desire to understand the trajectory of Chameleon’s life. This is a man who started off in 1997 singing in dresses with self-described “monki punk” band Boo, and has ended up as one half of an airbrushed duo, defending the singing of Die Stem and rhapsodising about gun ownership.

It strikes me, belatedly, that it was a similar impulse that drove me to interview Piet Botha.

There’s something about Afrikaans rock musicians that marks them as different to other South African rock artists. Perhaps it’s the fact that many of them, from Bittereinder to Brixton Moord en Roof Orkes, from Dozi to Ddissel-blom, must at some time face a real, stark choice between commercial success and artistic integrity, and that choice is always imbricated with a sense of cultural conflict.

Chameleon insists that all his choices have been for artistic reasons, even 7de Hemel, his collection of songs from the long-running soap opera 7de Laan.

He is a difficult interviewee, because he displays both a coruscating intelligence and a suspiciously polished patter. Often, I can’t tell which of his stories are immaculately rehearsed PR, and which honest insights. Perhaps they can be both. Certainly, when I ask him about the importance of religion in his music, he trots out a story he’s told to other interviewers. And it’s a story that doesn’t particularly answer the question.

“The life of the average bank clerk is more exciting than the life of the average musician. Because in a day’s life, that bank clerk is a father to his children, a husband to his wife, and a colleague. He’s also a buddy with his pals in the bar. He has many different aspects to him and he appears different to different people. He has that natural chameleonism, which is something I see in all people and I just decided to identify with that, which is why I named myself [after the chameleon].

“But most musicians are, like: ‘I’m going to be a rock artist, and then I’m going to commit to that for the rest of my life.’ And … they do. So there’s less variety in most musicians’ career than in the average day of a bank clerk. And I’ve just never been into that.”

Chameleon talks in a clipped, thoughtful way, without the breathy effusiveness of a normal interviewee. You can hear every word distinctly, as if he is holding them physically in his mouth and then releasing them into the world complete.

It’s both a measure of his caution and a reminder that here is a man who has perfect control over his voice. To hear Chameleon sing songs such as Apie, Klein Klein Jakkalsies and Boo’s Sting is the aural equivalent of watching an acrobat doing crazy, joyous tumbles on the corrugated iron roof of a burning building.

What to make of Chameleon’s tale of how he turned Daniella Deysel, his partner on Posduif and someone who had never sung before, into a singer from scratch? He says it took him a year.

“The way I did it was I had her sing with me. I used to take her to live shows, so she could get used to the environment, the lack of glamour. I got her on stage during sound checks, and got her to sing one or two songs to the bar lady and the sound engineer, to get used to this microphone thing. Then I had her doing backing vocals on my previous album, to get used to the studio. Then it was hours and hours of us singing together.

“A lot of young singers, especially when they’re insecure, import emotional widgets, they channel someone like Christina Aguilera, and then they become more confident.”

Chameleon rummages on the restaurant table and picks up a sugar packet. He squints at the trite aphorism printed there, and then sings it, artificially elongating some of the vowels. “‘A good laugh makes us beeeetter friends.’ I don’t buy that, that emotion. You didn’t feel it, you did it. You’re performing the emotion.” He talks about how he forced Deysel to confront her artificiality, and overcome it.

“I give her credit for going through that. It’s a very cruel process. And that’s why she sounds like nobody else, that’s why I sound like nobody else. I don’t try to imitate anyone but myself.”

Chameleon and Deysel’s new album is proof that the process worked. The eponymous Posduif, for example, is a lovely song, its simple emotion teetering on the edge of sentimentality, and it leaves it up to the listener to decide if you want to wince or smile.

Don’t watch the video on YouTube, though. There, the choice is made for you: it’s wince all the way, as the video is peppered with poppie cliches, from the pink bow on Deysell’s black nightie to the obligatory simpering blonde sucking a lollipop. Truly, it does the song no service, although it does have a weirdly dark ending when our two protagonists end up with different partners.

I ask Chameleon why he has chosen to collaborate with Deysel. After making two albums as tributes to Ingrid Jonker’s poetry, it jars a little that he would be inspired by a poet who, with the best will in the world, can’t be compared with the woman who wrote Die kind wat doodgeskiet is deur soldate by Nyanga.

“She’s 24, and her poetry excites me for that reason: she’s a voice of a younger generation of Afrikaans-speaking people, who busies herself with wordsmithing.”

I tell Chameleon that the overwhelming feeling I get from the album is of youth. It’s an old youth, a youth that always exists in the present, so that you can’t imagine it getting older, and you can’t think of it as ever having been younger. Chameleon’s response to this gobbledegook is to express polite surprise. “Oh, so you’ve listened to it?”

I’m nonplussed by the question. Why would anyone interview a musician without having listened to his album? “Well, not all of your colleagues have, strangely.” It’s a sad indictment of the state of music journalism.

At one point, Chameleon asks me whether I have noticed that he stopped following me on Twitter, and tells me: “This is off the record — because surely the personal has no place in an interview.” Weird. What sort of stunted coverage are musicians used to if they believe that journalists just want to recycle cute stories for their readers? Or perhaps it’s a reflection of how Chameleon would prefer interviews to be. I tell him that this is most decidedly on the record.

It is revealed, somewhat awkwardly, that he and I unfollowed each other on Twitter at the same time. It was many months ago, and he struggles to remember precisely what I did to offend him, and what upset me. He ruminates that it was possibly something anti-Afrikaner.

Affronted by this, I remind him that it had nothing to do with culture, but was over our diametrically opposed views on gun control. He’s relieved: “Hey, it was about that! That was it, thank goodness.”

It would be simple here, for the journalist looking to score easy points, to posit an unconscious elision in Chameleon’s mind between big guns and Afrikaner identity, but this would be a cheap trick. What is true, though, is that we’re getting to the meat of the interview now, and that’s the bit where we need to talk about Chameleon’s views on gun ownership, Die Stem, and that part of South African identity that is Afrikaner.

Sometimes, when rightwingers turn your Twitter stream into a perverted re-enactment of Bloedrivier, you’re tempted to believe that these tropes are convenient marketing tools for ageing musicians and politicians. But to grant them the right to be the spokespersons on these issues would be to belittle very real concerns, and to do a disservice to someone like Chris Chameleon.

Take gun ownership, the issue that caused Chameleon and I to part ways on Twitter. It’s an area where Chameleon strays into the paranoid territory of the American libertarian.

“The thing about a gun that I like is that it doesn’t pose a greater threat to the people than most other things, but it poses a greater threat to the government. For me the government everywhere is the enemy. I don’t believe in a government, I believe in the sovereign individual. From a personal perspective, I need you to understand that about me.”

“Also”, Chameleon tells me, “I’m a hunter, and I really enjoy the gun as a tool.” Then he tells me a strangely poignant story to illustrate this philosophy. I can tell that it’s a story he’s trundled out before for public consumption, but it’s still vividly revealing, and perhaps helps me a little to understand one of the questions that prompted me to do the interview: What journey brought Chris Chameleon from the cross-dressing freedom of Boo to where he is now?

“I have a knife in my house. In 2004 I was attacked in my house, and I had 60 stitches on wounds all over my body, and I couldn’t wear a Boo dress after that because my legs were too cut up. I still have the knife that they took from my kitchen and used to stab me. I still prepare meals with that knife. This evening someone is coming for dinner, and that knife will be used to make the meal. Because it’s a tool.

“And I’ve separated myself from whatever meaning was given to it at that time, and I’m looking at the usefulness of it, and its essence. In essence, it is neither evil nor good. It’s just a tool.” It’s a variation on the old NRA bumper sticker, that guns don’t kill people, people kill people. Chameleon uses the same logic to defend Steve Hofmeyr’s recent singing of Die Stem at Afrikaans cultural festival Innibos.

“I view Die Stem like that as well. There is nothing offensive in Die Stem. I had an argument with Max du Preez about that. I said, it’s an innocent song that praises god and nature, and it’s not against anyone, and he said the innocence disappeared after 1948. But [I believe that] there’s nothing offensive in it. You have to disassociate yourself from the meaning of things, otherwise you lose a lot of good and useful things. For instance, those trains the Jews were transported on to concentration camps. Are we not allowed to use those tracks again?”

In 2011, Chameleon sided with Hofmeyr in deriding Bono’s comments about the Kill the Boer song, arguing that “to say you have to choose the right community for such songs is similar to condoning racist remarks at a braai”.

He seems blithely unaware this criticism can be applied to his own defence of Hofmeyr. “The fact that 40 000 people sang [Die Stem] with him means that, if not anywhere else, at least there it was appropriate, because it resonated with the people who were there.”

As I end the interview, Chameleon says: “I will not be looking out for this article.” I can understand why. It seems sad that you can’t put an album into the world without also having to endure having your personal philosophies challenged. On the other hand, you’d be a pretty boring artist if you weren’t also challenging your audience, so perhaps it’s the inevitable symmetry that goes with being as talented and intriguing a performer as Chris Chameleon.